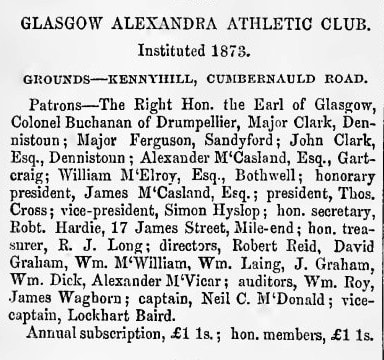

The little volume by 'Straw Hat' on Rugby & Association Football was one of Dean's Champion Handbooks, which had attractive cover designs and were published to capitalise on the growing desire of the population to take up sport. They came out in the 1890s, and are now very difficult to find.

'Straw Hat' was the pseudonym of James Jeffery, who had an interesting story as a talented sportsman who combined school teaching with journalism.

Meanwhile, he also carved out a career as a sports writer, initially concentrating on angling as 'Straw Hat' in the Licensed Victuallers' Gazette. His enthusiasm for sports must have appealed to Dean & Son Ltd of Fleet Street, who had started a series of sporting handbooks in the early 1890s based on previously published works about cricket, cycling and swimming. To expand their range, they employed Jeffery and he churned out several books including Football, Croquet, Tennis and Rowing, with an adaptation of the book on Swimming. The cheap editions sold for sixpence, while the hardbacks with colourful covers were a shilling.

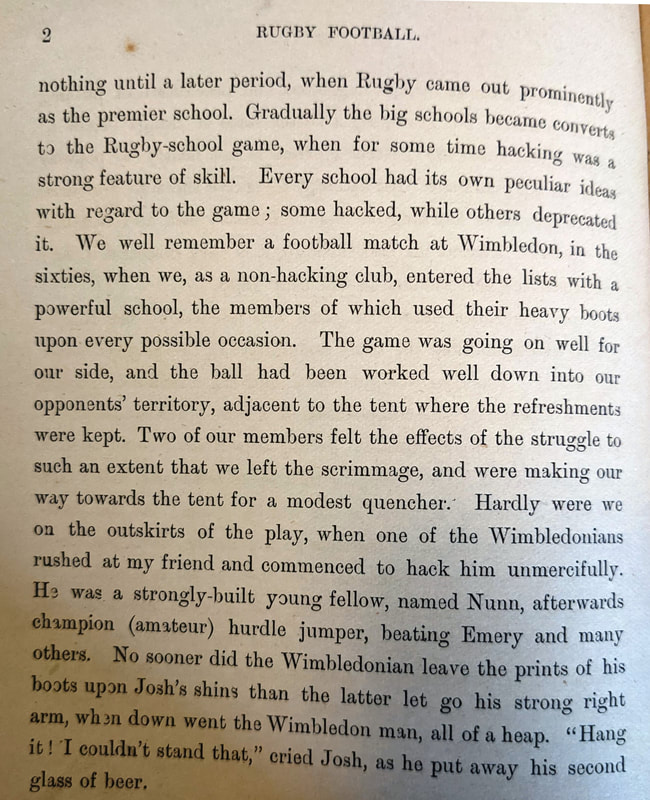

While most of his book about football is about playing technique, he does provide an interesting anecdote about the early days of football before codification, describing a match played at Wimbledon in the 1860s when his team, which was a 'non-hacking club', came up against a school which did play the hacking game. I believe, from his description, that 'Josh' was the athlete GR (George Richard) Nunn, who was schooled at Epsom.

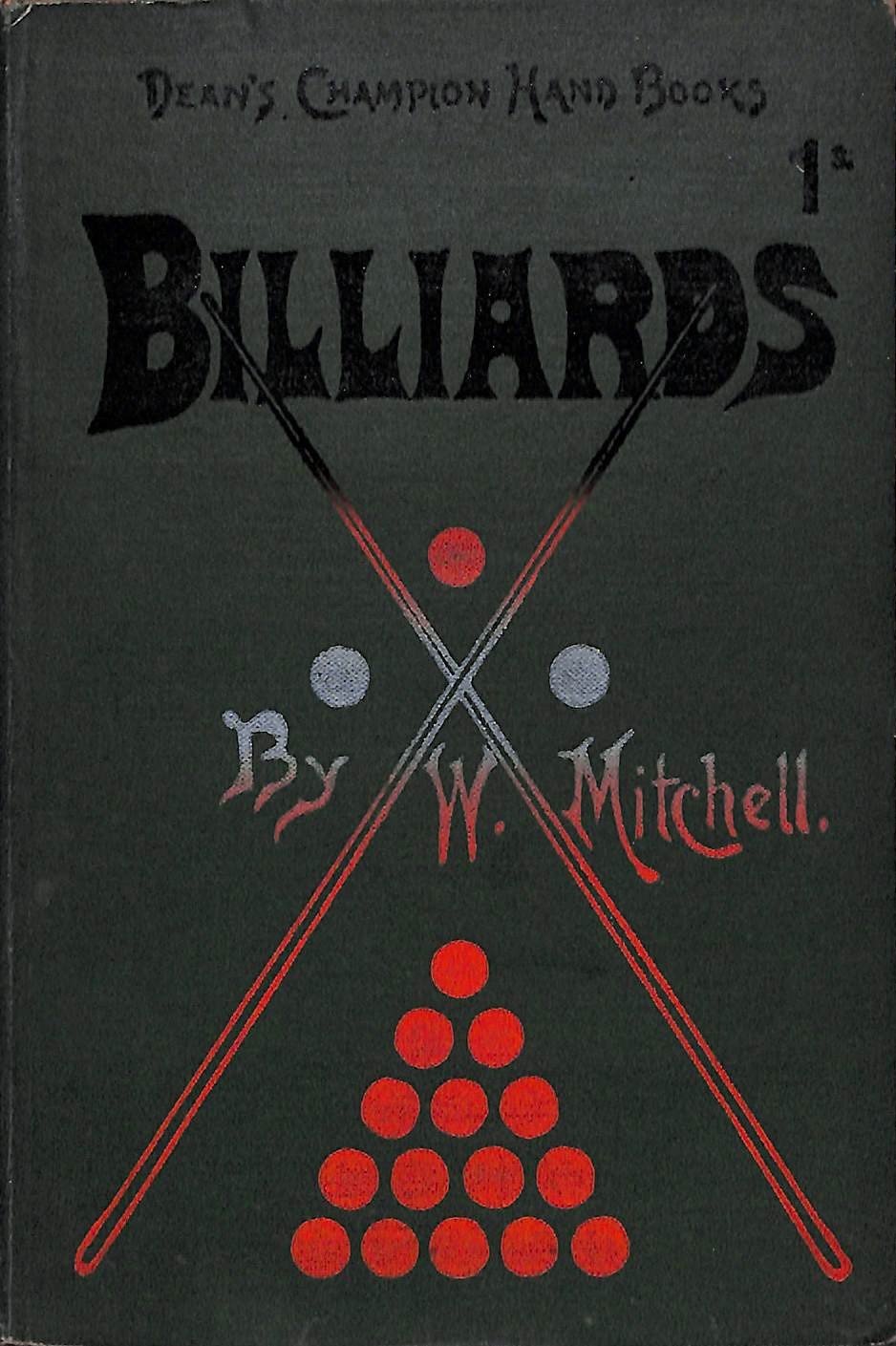

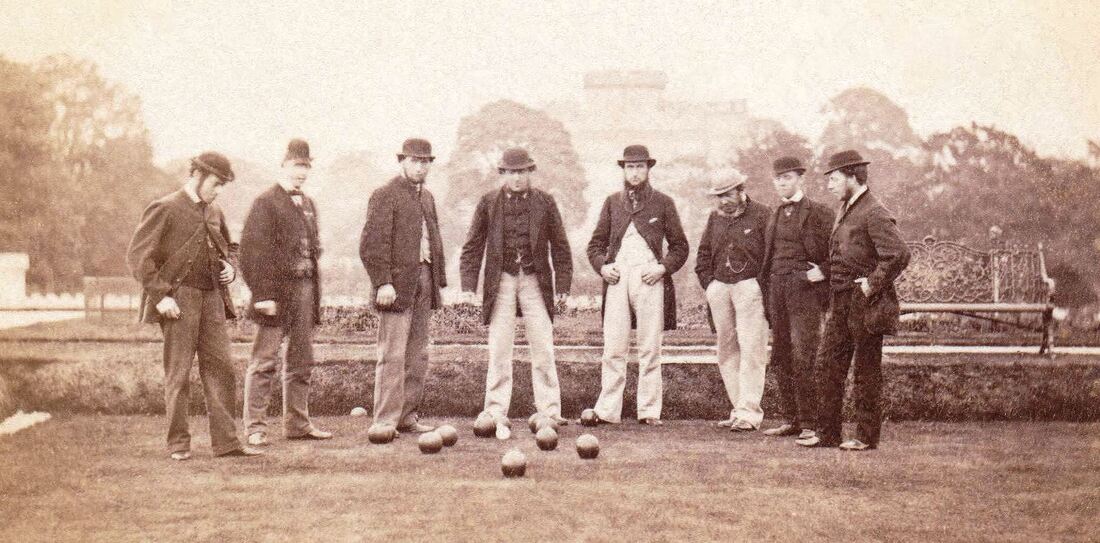

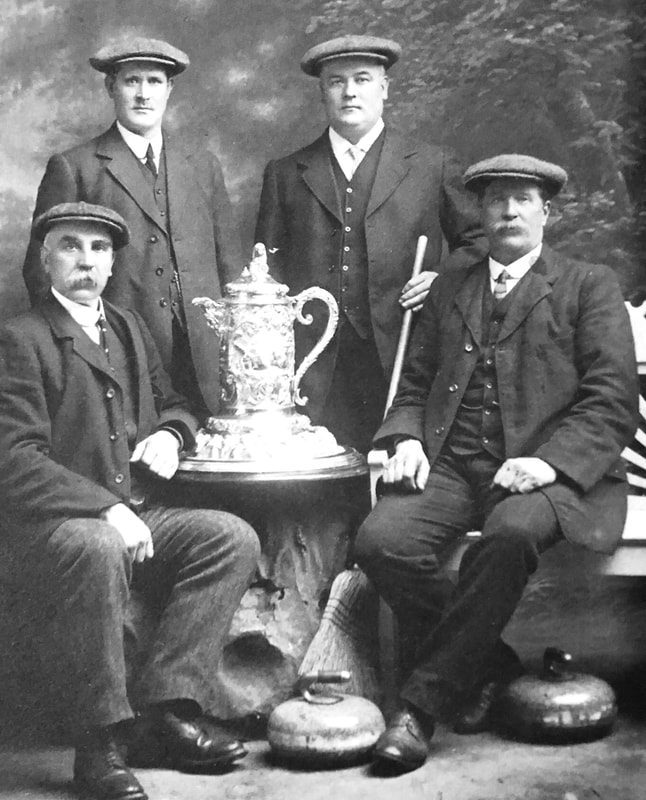

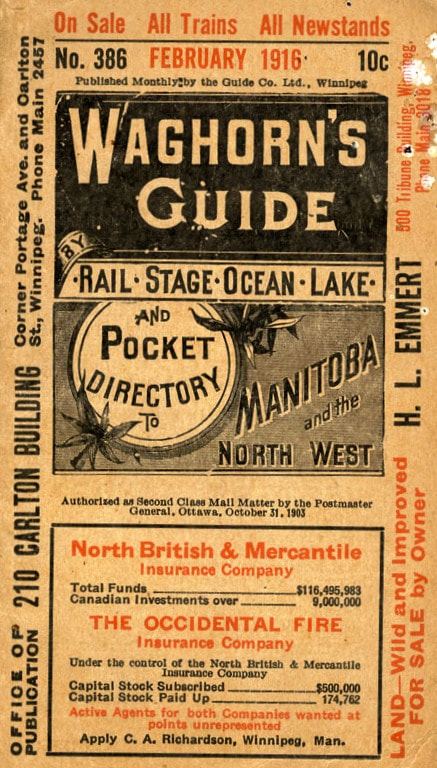

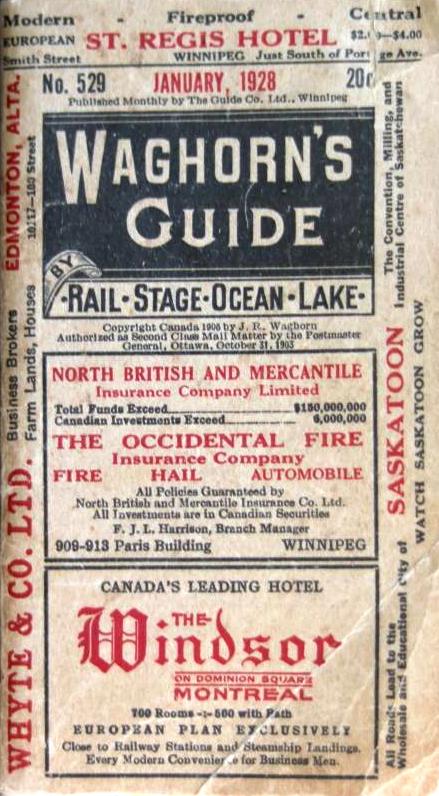

Illustrated below are three more of Dean's Champion Handbooks, on billiards, swimming and golf. The images come from dealer catalogues, so they are not particularly sharp.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed