Adventures in a canoe

One of Arthur Kinnaird's more unusual sporting accomplishments was to win a canoe race at the 1867 Universal Exhibition in Paris. However, his enthusiasm for paddling nearly ended in disaster in a storm off the west coast of Scotland with his life – and that of a future Prime Minister – at risk.

The story began in 1866 when the Scotsman John MacGregor, an enthusiast who was devoted to canoeing, published a volume of exploits and daring voyages, A thousand miles in the Rob Roy canoe on the rivers and lakes of Europe. This book brought the sport to a vast audience and he capitalised on its success by forming the Canoe Club in London. It proved immensely fashionable and attracted many young and aristocratic devotees, among them the Prince of Wales, whose patronage led it to becoming the Royal Canoe Club in 1873, the title it still has today at its Teddington base on the River Thames.

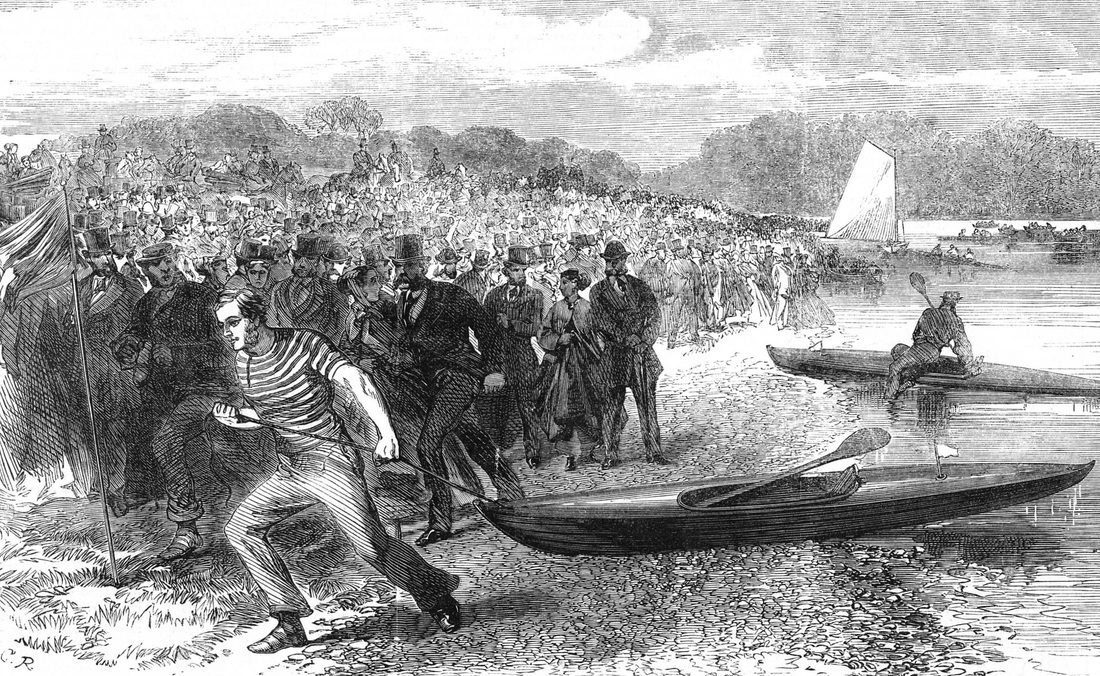

Arthur was hooked by the craze and commissioned a carpenter, probably Searle of Lambeth, to build an oak Rob Roy canoe for £15. He named his boat Rossie, which was delivered in time for Arthur to take part in the Canoe Club's first regatta, or grand muster, in April 1867 when 15 canoeists met at the Swan Inn. Led by John MacGregor, they paddled in procession up river to Thames Ditton for the regatta, which was such a success that the Illustrated London News published an engraving of the scene, showing the large crowd of spectators. The paper described how Arthur won the captain’s challenge cup with victory in the canoe chase:

'The great event of the day was the canoe chase over land and water. Four flags were arranged at the angles of a square, and the starting-point was fixed midway between them. Mr. Inwards, the mate, was selected as chevy, and had two minutes law, after which the remaining canoes rushed after him. The course was diagonally across, round all the flags, and back to the starting-point. The excitement was very great when Mr. Kinnaird and the purser (Col. Wright) went for the same flag, and finally emerged from behind a tree, 'heads and tails' to the water side. The purser was in first with the head of his boat in the right direction, so away he went to the next flag. Kinnaird's boat, however, had its nose the wrong way, so he bucketed across, jumped on land, and tore away to the next flag; here the purser rounded the flag together with the owner of the Rossie. In the end Mr. Kinnaird won, the purser being 2nd, and the chevy 3rd.'

That summer, MacGregor was invited by the French Emperor Napoleon to demonstrate his canoes at the Paris Exhibition and Arthur began his summer vacation as part of the delegation of English canoeists who travelled to Paris. MacGregor, ever the opportunist, had paddled all the way there, and in his subsequent memoir, The Voyage Alone in the Yawl Rob Roy, he related the excitement of the canoe chase on 9 July, won by Arthur Kinnaird ('the Englishman'):

'Two prizes were offered at the Paris Regatta for a canoe chase, open to all the 'peoples'. Five French canoes entered, but there was only one English canoeist ready in his Rob Roy to meet all comers. The canoes were drawn up on land alongside each other, and with their sterns touching the lower step of the grand stand. All dashed off together on being started, and ran with their boats to the water. The Frenchmen soon got entangled together by trying to get into their boats dry; but the Englishman had made up his mind for a wetting, and it might as well come now at once as in a few minutes after, so he rushed straight into the river up to his waist, and therefore, being free from the crowding of others, he got into his boat all dripping wet, but foremost of all, and then paddled swiftly away.

'The rest soon followed; and all of them were making to the flag boat anchored a little way off, round which the canoes must first make a turn. Here the Englishman, misled by the various voices on shore telling him the (wrong) side he was to take, lost all the advantage of his start; so that all the six boats arrived at the flag-boat together, each struggling to get round it but locked with some other opponent in a general scramble. Next, their course was back to the shore, where they jumped out and ran along, each one dragging his boat round another flag on dry land, amid the cheers and laughter of the dense group of spectators, who had evidently not anticipated a contest so new in its kind, and so completely visible from beginning to end.

'Once more the competing canoes came swiftly hack to shore, and were dragged round the flag, and another time paddled round the flag-boat; and now he was to be winner who could first reach the shore and bring his canoe to the Tribune: a well-earned victory, won by the Englishman, far ahead of the rest.'

Arthur's appetite for adventure was whetted and on his return from Paris he was invited with his Cambridge (and Eton) friend Arthur Balfour to Dunvegan Castle on the Isle of Skye, ancestral home of family friend Reginald MacLeod, later Chief of the Clan MacLeod. The trio had decided to circumnavigate Skye in their canoes, a trip which nearly ended in disaster.

On the first two days' journey down the west coast they found hospitality in a shooting lodge and a farm, but on the third night the spirit of adventure started to wane as they found only a deserted cottage. Things took a turn for the better as they headed across 16 miles of open water to the island of Rum, where they stayed a few nights as guests of Captain William MacLeod of Orbost, who rented the island from Balfour's grandfather. Leaving Balfour on Rum, Arthur and MacLeod crossed to Eigg, where they camped overnight in a cave with a grisly history: it was where, in 1515, the Macdonald clan of Eigg had sheltered from an attack led by MacLeod's ancestors but were discovered, and trapped inside. The attackers burned brushwood at the mouth of the cave, and 395 men, women and children were smoked to death.

Until then, the weather had been kind, but on their way back to Rum a violent storm blew up. The little boats were tossed around by the waves and it was only with great difficulty that the exhausted pair navigated their way back to safety. They could easily have drowned or been dashed on the rocks.

Reunited with Balfour, they rested on Rum until the weather abated, then decided to continue and struck out for the Skye coast; but a few days later, exhausted, they eventually gave up at Portree and loaded the canoes onto carts to return overland to Dunvegan. It is interesting to speculate how the course of world history could have changed if the expedition had indeed ended in disaster, as Arthur Balfour not only became Prime Minister in 1902, he authored the Balfour Declaration of 1917 that remains central to Middle East politics to this day.

Balfour later admitted that 'a Rob Roy canoe was no proper sea-going craft' and called it 'a very hare-brained adventure'. He remarked candidly that the trip could easily have proved fatal, and posed the rhetorical question in his autobiography, 'It may be asked why our legal guardians (I was under twenty) permitted us to run risk so obviously useless? At the time I never heard the question raised.'

*The full story of these adventures is related in First Lord of Football.

The story began in 1866 when the Scotsman John MacGregor, an enthusiast who was devoted to canoeing, published a volume of exploits and daring voyages, A thousand miles in the Rob Roy canoe on the rivers and lakes of Europe. This book brought the sport to a vast audience and he capitalised on its success by forming the Canoe Club in London. It proved immensely fashionable and attracted many young and aristocratic devotees, among them the Prince of Wales, whose patronage led it to becoming the Royal Canoe Club in 1873, the title it still has today at its Teddington base on the River Thames.

Arthur was hooked by the craze and commissioned a carpenter, probably Searle of Lambeth, to build an oak Rob Roy canoe for £15. He named his boat Rossie, which was delivered in time for Arthur to take part in the Canoe Club's first regatta, or grand muster, in April 1867 when 15 canoeists met at the Swan Inn. Led by John MacGregor, they paddled in procession up river to Thames Ditton for the regatta, which was such a success that the Illustrated London News published an engraving of the scene, showing the large crowd of spectators. The paper described how Arthur won the captain’s challenge cup with victory in the canoe chase:

'The great event of the day was the canoe chase over land and water. Four flags were arranged at the angles of a square, and the starting-point was fixed midway between them. Mr. Inwards, the mate, was selected as chevy, and had two minutes law, after which the remaining canoes rushed after him. The course was diagonally across, round all the flags, and back to the starting-point. The excitement was very great when Mr. Kinnaird and the purser (Col. Wright) went for the same flag, and finally emerged from behind a tree, 'heads and tails' to the water side. The purser was in first with the head of his boat in the right direction, so away he went to the next flag. Kinnaird's boat, however, had its nose the wrong way, so he bucketed across, jumped on land, and tore away to the next flag; here the purser rounded the flag together with the owner of the Rossie. In the end Mr. Kinnaird won, the purser being 2nd, and the chevy 3rd.'

That summer, MacGregor was invited by the French Emperor Napoleon to demonstrate his canoes at the Paris Exhibition and Arthur began his summer vacation as part of the delegation of English canoeists who travelled to Paris. MacGregor, ever the opportunist, had paddled all the way there, and in his subsequent memoir, The Voyage Alone in the Yawl Rob Roy, he related the excitement of the canoe chase on 9 July, won by Arthur Kinnaird ('the Englishman'):

'Two prizes were offered at the Paris Regatta for a canoe chase, open to all the 'peoples'. Five French canoes entered, but there was only one English canoeist ready in his Rob Roy to meet all comers. The canoes were drawn up on land alongside each other, and with their sterns touching the lower step of the grand stand. All dashed off together on being started, and ran with their boats to the water. The Frenchmen soon got entangled together by trying to get into their boats dry; but the Englishman had made up his mind for a wetting, and it might as well come now at once as in a few minutes after, so he rushed straight into the river up to his waist, and therefore, being free from the crowding of others, he got into his boat all dripping wet, but foremost of all, and then paddled swiftly away.

'The rest soon followed; and all of them were making to the flag boat anchored a little way off, round which the canoes must first make a turn. Here the Englishman, misled by the various voices on shore telling him the (wrong) side he was to take, lost all the advantage of his start; so that all the six boats arrived at the flag-boat together, each struggling to get round it but locked with some other opponent in a general scramble. Next, their course was back to the shore, where they jumped out and ran along, each one dragging his boat round another flag on dry land, amid the cheers and laughter of the dense group of spectators, who had evidently not anticipated a contest so new in its kind, and so completely visible from beginning to end.

'Once more the competing canoes came swiftly hack to shore, and were dragged round the flag, and another time paddled round the flag-boat; and now he was to be winner who could first reach the shore and bring his canoe to the Tribune: a well-earned victory, won by the Englishman, far ahead of the rest.'

Arthur's appetite for adventure was whetted and on his return from Paris he was invited with his Cambridge (and Eton) friend Arthur Balfour to Dunvegan Castle on the Isle of Skye, ancestral home of family friend Reginald MacLeod, later Chief of the Clan MacLeod. The trio had decided to circumnavigate Skye in their canoes, a trip which nearly ended in disaster.

On the first two days' journey down the west coast they found hospitality in a shooting lodge and a farm, but on the third night the spirit of adventure started to wane as they found only a deserted cottage. Things took a turn for the better as they headed across 16 miles of open water to the island of Rum, where they stayed a few nights as guests of Captain William MacLeod of Orbost, who rented the island from Balfour's grandfather. Leaving Balfour on Rum, Arthur and MacLeod crossed to Eigg, where they camped overnight in a cave with a grisly history: it was where, in 1515, the Macdonald clan of Eigg had sheltered from an attack led by MacLeod's ancestors but were discovered, and trapped inside. The attackers burned brushwood at the mouth of the cave, and 395 men, women and children were smoked to death.

Until then, the weather had been kind, but on their way back to Rum a violent storm blew up. The little boats were tossed around by the waves and it was only with great difficulty that the exhausted pair navigated their way back to safety. They could easily have drowned or been dashed on the rocks.

Reunited with Balfour, they rested on Rum until the weather abated, then decided to continue and struck out for the Skye coast; but a few days later, exhausted, they eventually gave up at Portree and loaded the canoes onto carts to return overland to Dunvegan. It is interesting to speculate how the course of world history could have changed if the expedition had indeed ended in disaster, as Arthur Balfour not only became Prime Minister in 1902, he authored the Balfour Declaration of 1917 that remains central to Middle East politics to this day.

Balfour later admitted that 'a Rob Roy canoe was no proper sea-going craft' and called it 'a very hare-brained adventure'. He remarked candidly that the trip could easily have proved fatal, and posed the rhetorical question in his autobiography, 'It may be asked why our legal guardians (I was under twenty) permitted us to run risk so obviously useless? At the time I never heard the question raised.'

*The full story of these adventures is related in First Lord of Football.