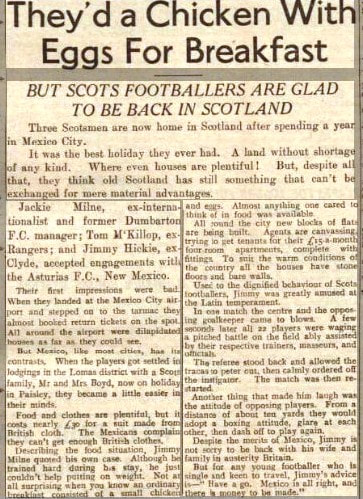

Little wonder that three of our international starts jumped at the opportunity, and for a full year Jackie Milne, Tom McKillop and Jimmy Hickie lived the dream in Mexico City. This little-known episode was brought to mind as Scotland's national team prepare to face Mexico in the Azteca Stadium for the first time.

The adventure was chronicled in a series of articles by Jack Harness in the Sunday Post, starting in May 1946 when he revealed that William Raeside, the Scottish coach of Asturias FC, had come home from Mexico to recruit players. The three he selected were approaching the end of their careers and were all able to negotiate free transfers. Jackie Milne was player-manager of Dumbarton after a career with Blackburn Rovers, Arsenal (where he was part of the team that won the Football League in 1937/38) and Middlesbrough. Tom McKillop had spent a decade with Rangers, winning the Scottish League twice, while Jimmy Hickie was an established defender with Clyde, winning the Scottish Cup in 1939. They all had pre-war international honours, Milne having twice played against England, McKillop won one cap against Holland in 1938, while Hickie was selected for the Scottish League the same year.

After a rush to get passports and negotiate their release from their clubs, they duly set off for Mexico in June 1946, flying from Prestwick via New York in an era when transatlantic air travel was a rare luxury. They were immediately pitched into the Asturias side for a cup-tie.

Asturias was a mid-table Mexican side when they joined league and there was to be no fairy tale season as their league position hardly changed, finishing ninth in 1946/47. Still, it was a great experience and the three were preparing for the second year of their contracts when the club's Spanish and American owners suddenly withdrew their support. The players were effectively abandoned and had to return home.

Nonetheless, they told Jack Harkness of the wonderful experience, away from the shortages of post-war Britain. They lodged with a Scottish couple in the Lomas district of Mexico City, and found that food was plentiful, while the city was booming. The football took some getting used to - there were stories of mass fights and appalling refereeing - but they fitted in well.

The other factor in the tale is the role of Paisley-born William Raeside, who recruited them in the first place. He has a fascinating story as a Scottish coach abroad, having taken charge of clubs as diverse as Celta de Vigo in 1927 (under the assumed name of WH Cowan), and later across the Atlantic with Nacional of Uruguay, Newell's Old Boys in Argentina, Guadalajara in Mexico, and - somewhat incongruously - back in Britain with Cheltenham Town in the 1952/53 season. I'm going to look into his life in more detail in a future blog.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed