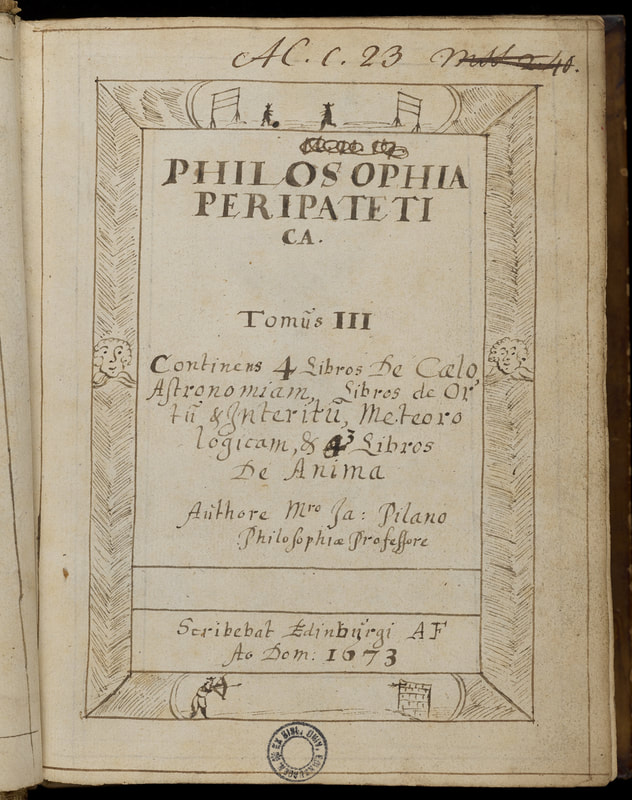

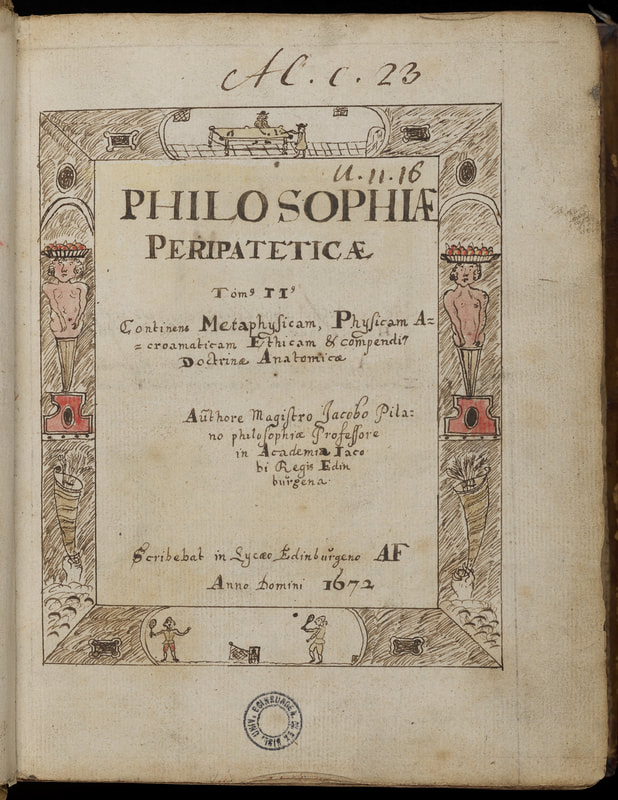

It was drawn by Archibald Flint, a student who graduated from Edinburgh University in 1673. He doodled extensively in the margins of his lecture notes (known as dictates) and on the title pages of two surviving volumes are four little pen sketches which show men – presumably students – taking part in sport. They depict billiards, tennis, football and target archery.

The importance of these drawings was first recognised by Charles Pringle Finlayson, who was keeper of manuscripts at Edinburgh University library. He wrote a lengthy analysis in the Scottish Historical Review, published in 1958, but his paper has been largely forgotten and deserves to be better known among sports historians.

Finlayson also notes that the Latin translation of one of James VI’s works calls football 'pila Scotica quae pede propellitur' (a Scottish ball which is propelled by the foot).

The drawings confirm that sport of various kinds had became respectable in late 17th century Scotland, when attitudes relaxed again after the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660. It was not just football: emerging from years of negativity by the Kirk and the civic authorities, golfers started to knock balls around Bruntsfield and Leith Links, horse racing began again on Leith Shore and Musselburgh, and bowling greens were laid out in the city by landowners on their estates.

Archery was strengthened by the founding in Edinburgh of the Royal Company of Archers in 1676, the nation's first sporting society. From Alexander Flint’s drawings we can deduce that tennis was popular – there was a tennis court at the Abbey of Holyroodhouse – and so was billiards.

Golf was also considered a suitable game for a student of that era, as Thomas Kincaid, an Edinburgh surgeon’s son, reveals in his diary for 1687-88. Aged about 26 years old, he played golf on Bruntsfield Links, 'near the Tounis College', and on Leith Links. Kincaid went on to describe 'the only way of playing at the Golve', giving instruction on how to adopt the correct stance and hit the ball, and elsewhere in his diary he outlined how golf clubs were made. He also developed a talent for archery and went on to be an active member of the Royal Company of Archers, becoming just the third winner of the Edinburgh Arrow in 1711.

It all goes to show that football games, archery butts, tennis courts and billiard tables were an accepted part of the landscape for Edinburgh gentlemen towards the end of the 17th century. The enthusiasm of the university authorities for some of these sports appears to have waned in the following century, before John Hope and his friends revived football as a respectable pastime when they founded their club in 1824.

With thanks for the Centre for Research Collections, Edinburgh University Library, for rephotographing Archibald Flint's dictates, and giving permission for reproduction.

CP Finlayson's article was entitled: Illustrations of Games by a Seventeenth Century Edinburgh Student. The Scottish Historical Review, Vol. 37, No. 123, Part 1 (April 1958), pp. 1-10.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed