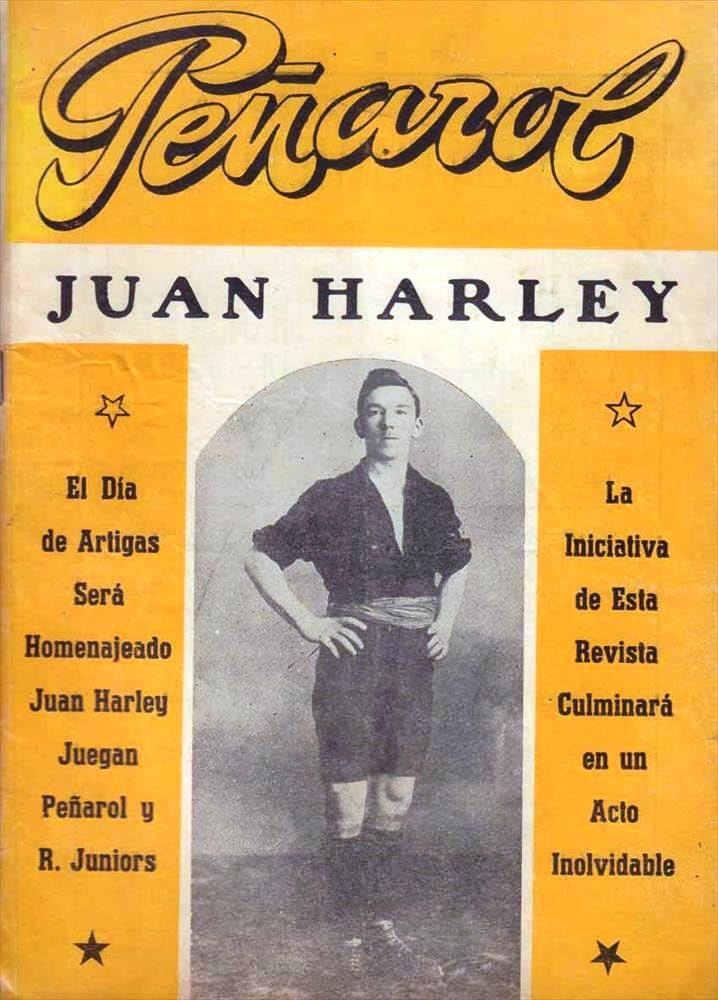

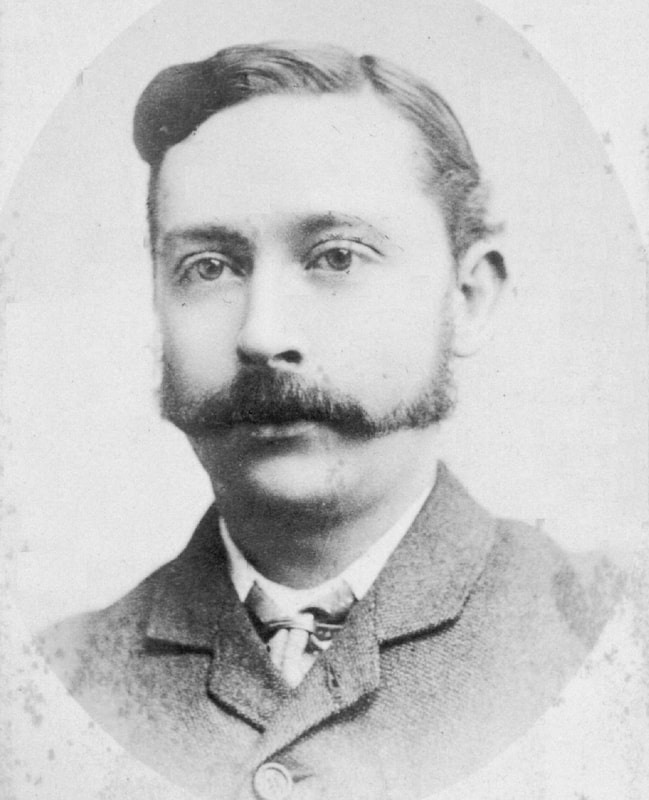

He overcame tragedy and challenges in his early life to be celebrated as the 'father of Argentine football' thanks to his work in establishing the game as a national obsession. Having set up a football league in 1893, then created a dominant football club, Hutton's footballing story is fairly well known (more so in Argentina than his native land, it has to be said) but his life in Scotland remains something of an enigma.

That prompted me to research the formative years of a boy orphaned before he was five years old, his entire family wiped out by disease, who found his vocation in education and sport.

Hutton's life events detailed below shed light on his family, childhood, school, university and early teaching career.

Family origins

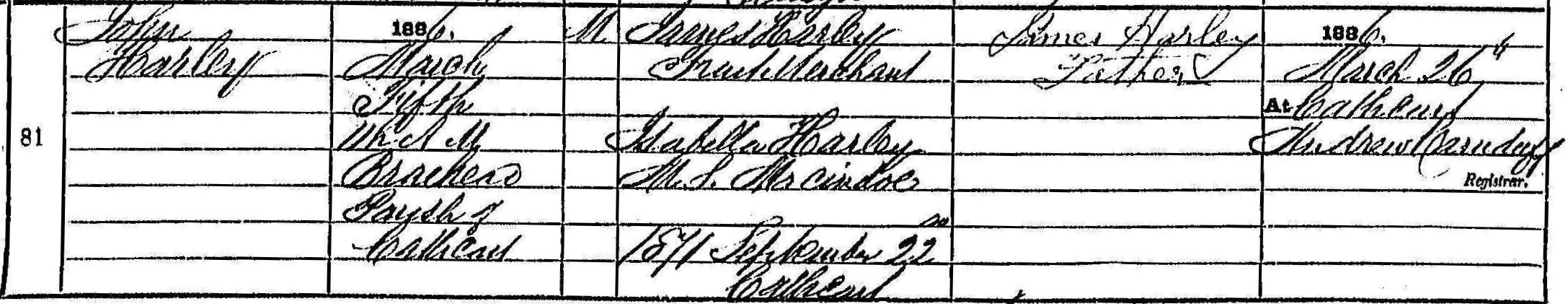

Alexander Watson Hutton was the second son of Robert Hutton, a grocer, and Helen (or Ellen) Watson. His parents were originally from the Dunfermline area in Fife but Robert moved to Glasgow in the 1840s to work as a grocer at the heart of the bustling Gorbals community of Laurieston, just south of the River Clyde in Glasgow. In time he opened his own shops, first in Bedford Street, then Norfolk Street and Nicholson Street.

Meanwhile Helen had been living with her family in Edinburgh, but after she married Robert on 12 November 1850 they set up home in the Gorbals in a tenement flat at 29 Eglinton Street. At first, everything went well: their first son, also Robert, was born in August 1851, while the grocery business prospered. Robert Hutton was able to employ shop staff and he opened a new outlet at 55 Eglinton Street, just along from the family home.

He was baptised the following month at Eglinton Street United Secession Church, which has also gone: it was converted to a cinema in 1921 and then destroyed by fire in 1932; it is now the site of the O2 Academy.

Multiple tragedies

Fate dealt the first cruel blow to the family as Robert Hutton fell seriously ill with tuberculosis and had to give up his shops. In January 1855 he moved with his wife and sons to live near Helen's family in Edinburgh, but it was a lost cause and he died there on 25 February. In an extraordinary twist of fate, the following day Helen gave birth to their third son, George.

Alexander, then just 20 months old, would never return to Glasgow as his father's death marked the start of a series of tragedies to hit the family. Younger brother George died aged 2 in May 1857, then his mother succumbed in January 1858, both from tuberculosis. They were buried together with Robert at Warriston Cemetery, although there is no headstone.

This left Alexander and his brother Robert as orphans, and they were taken under the wing of their grandmother (Helen's mother), Helen Bowman Watson who lived in Logie Green in Edinburgh. Sadly, the arrangement did not last long as she too died of tuberculosis early in 1862.

The Hutton brothers did well at the school, with Robert being a medallist in 1866, and Alexander was never to forget its positive influence; in the 1920s he endowed the Robert Hutton Prize for Modern Languages in memory of his brother, and also created a similar prize in his own name at George Watson's College.

Alexander left Daniel Stewart's in 1867 when he turned 14, with a solid grounding that would enable him to embark on adult life. He is recorded in the 1871 census as an apprentice grocer - the same trade as his father - but then switched his focus to education. That may have been prompted by the death of his brother Robert, who had been living with his uncle George in Cupar where he worked as a clerk but succumbed to tuberculosis and died in October 1871. Alexander was now the only survivor of the entire family.

A new family

Equally importantly, he also found a new family in Edinburgh.

By 1871 he was lodging in Brown Square, off Chambers Street, with Mrs Alexandrina Waters and her children Elizabeth, Catherine and William. Alexander became so close to the Waters family that when they moved in 1874 to 4 St Patrick Square, he joined them there and remained in the household until he emigrated.

After he went to Argentina the Waters family followed on and their lives remained intertwined in work, football and marriage: the teaching staff at the Buenos Aires English High School included Elizabeth and William, Mrs Waters was later on the staff as a house superintendent, and Catherine became his second wife.

University degree

Despite holding down a teaching job at George Watson's, Alexander was determined to further his own education and in 1877 he embarked on a four year Arts degree at Edinburgh University. It must have been a challenge to combine work with study, but he was helped by winning the Dundas Bursary which provided about £20 a year to fund his course.

His progress at the university can be followed by the class results published in The Scotsman: in April 1878 he passed his exams in Mathematics, a year later in Mental Philosophy, then in 1881 he graduated with an MA in Philosophy, gaining Second Class Honours.

Before he left, however, he needed a recruit. In December he placed his own advert for a female teacher to join the Scotch School as Infant, Junior and Sewing Mistress. The job went to Margaret Budge, also a teacher at George Watson's, and as he went on to marry her, the suspicion is that they were already close and he used the opportunity to ensure she could travel out with him.

The last mention of Alexander in the local press came in mid-January when he advertised for sale a 50 inch Hillman & Herbert 'Premier' bicycle, which conjures up images of this pioneer riding round the streets of Edinburgh on his penny-farthing.

Leaving his life in Scotland behind, he set sail for Argentina, arriving in Buenos Aires on 25 February 1882 to start work.

Football in Scotland

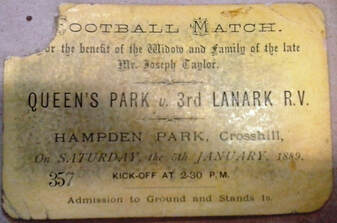

Despite uncovering so much detail of his early life, there is one thing missing: football. A detailed search of the Scottish press has so far failed to turn up any mention of him taking part in a football match, or indeed any kind of sport. Later interviews he gave in Argentina simply said that he played football as a young man in Scotland without giving any specifics, so he may have been enthusiastic but he was clearly not a top level player.

In some respects it is curious that he was so passionate about football after an Edinburgh upbringing (he had no real connection to Glasgow apart from his birth). During his schooldays at Daniel Stewart’s there was no organised recreation for the boys, while George Watson's did have a sporting ethos but the emphasis was on rugby in the winter and athletics and cricket in summer. As he taught at the junior school, presumably he supervised recreation for the boys in his charge, but he had no recorded involvement in school sporting activities or team games.

Life in Argentina

After two years at the Scotch School he left to found the English High School in 1884 where he had the opportunity to encourage sport for the pupils. He built an open air swimming pool and is said to have imported the first leather footballs to the country.

In a lengthy interview he gave to El Grafico in 1933 to mark his 80th birthday, 'Alejandro' reminisced about the early days, and told how the balls were impounded by customs officials who demanded to know what they were for.

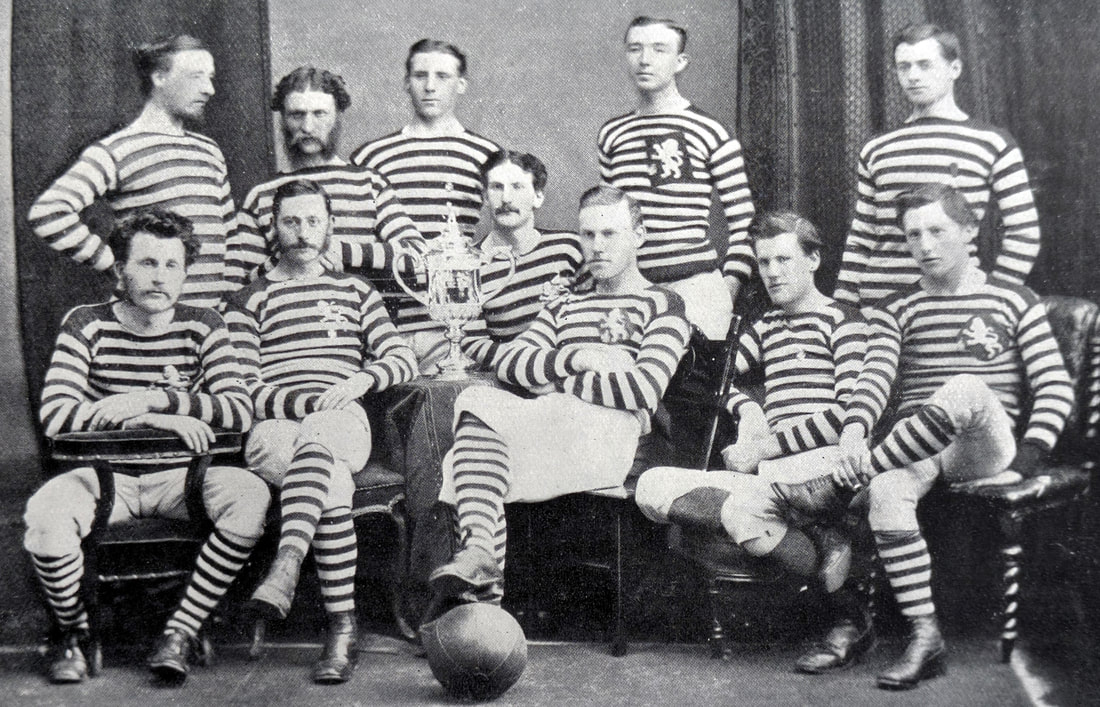

That may have coincided with the arrival of William Waters to work at the school, which some accounts date to the summer of 1886 although he was already a member of staff the previous year. Born in 1865, William (known as Guillermo) certainly made an impact on the football field as he went on to captain St Andrews, winners of the country's first league competition, before his early demise in 1906.

Also on the school staff was Margaret Budge, who Alexander married on 27 March 1885 at St Andrew's Church in Buenos Aires. They had three children: Arnold Pencliffe Watson Hutton 1886-1951 (who became a prominent footballer and an Argentina international), Edith Elena Watson Hutton 1888-1971 (married name Stocks), and Mabel Lilian Watson Hutton 1890-1979 (married name Mitchell).

Margaret died in August 1893 of pancreatic cancer and Alexander remarried Catherine (or Kate) Waters on 19 June 1902, with no further children.

By the time of his retirement from teaching in 1910, the English High School was said to be the largest, the best ventilated and the healthiest private school in Buenos Aires.

While he remained in Buenos Aires, he retained close links to Scotland and returned several times for visits. He died on 9 March 1936, age 82, and was buried in British Cemetery at Chacarita, where his grave remains a place of pilgrimage for football fans.

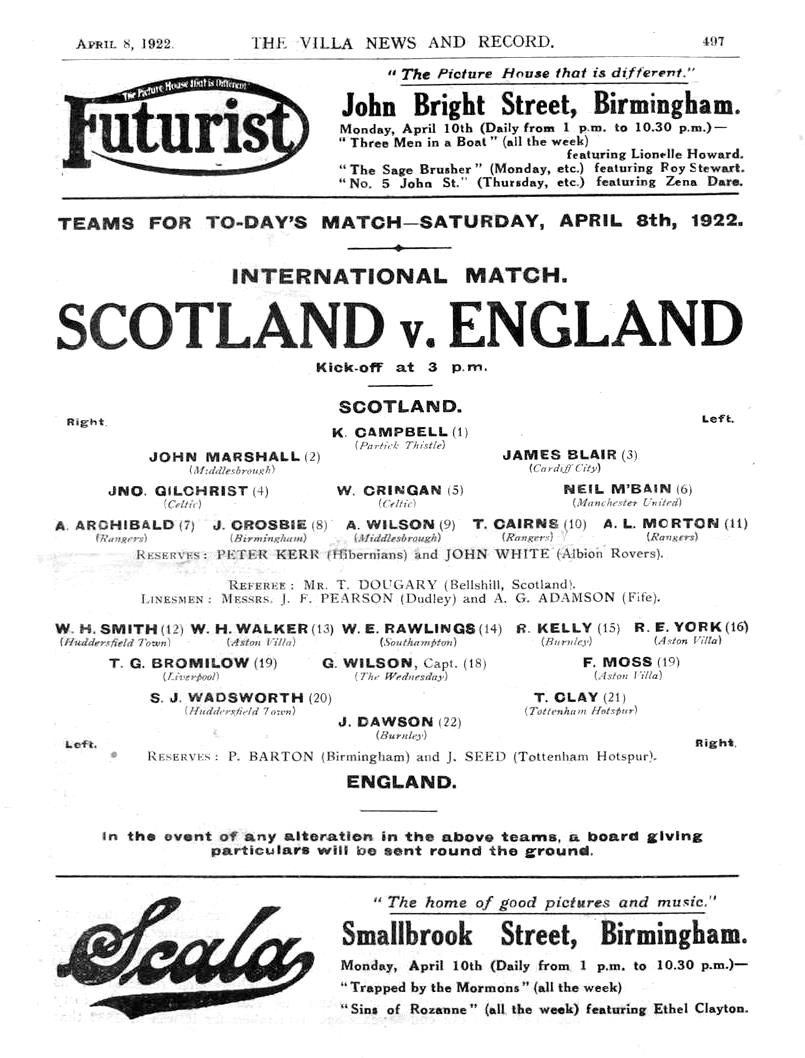

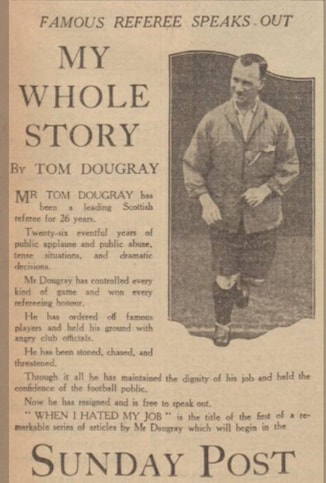

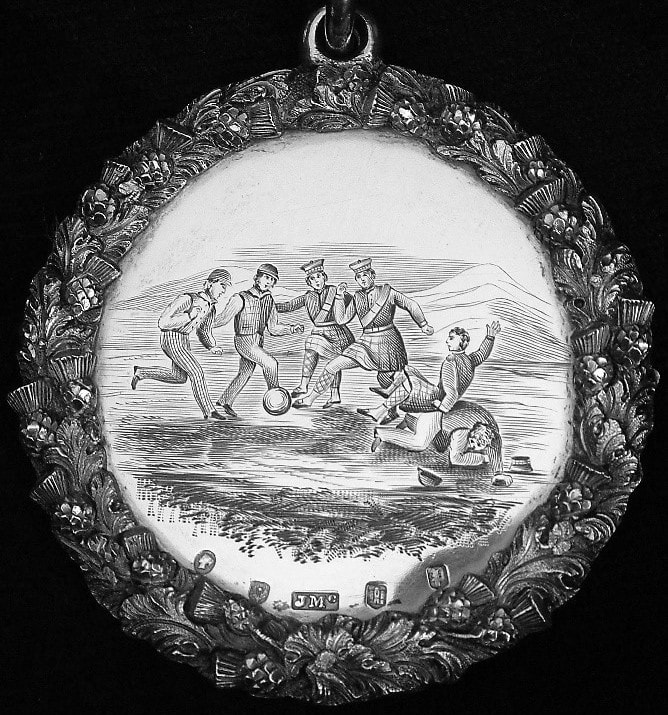

Hutton's legacy as the 'father of Argentine football' relates to his prominent role in establishing the sport on a sound footing. In February 1893 he was appointed President of the relaunched Argentine Association Football League (an earlier attempt in 1891 had foundered with the death of the President, Frank Woolley), which later became the Argentine Football Association. Then in 1898 he backed the foundation of the English High School football team (later Alumni) which won the First Division ten times by 1910 before it was disbanded.

The football fame of Alexander Watson Hutton belongs to his adopted country, and his impact can be explored in more detail through the links posted below. But his story really started back home in Scotland, and I hope this research contributes to a better understanding of the challenges he overcame.

Further links and research

A film of his life, Escuela de Campeones, was made in 1950 (see poster below) and is available on youtube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FmU3nD3y4Pc

A new book Alumni - El Mito [The Mythical Alumni] tells the story of Hutton's football club. Superbly illustrated, it is published in Argentina by Martin Emanuel de Vita who has made it available as a free download: https://heyzine.com/flip-book/3c5bfe5b66.html

Hutton first came to national notice in Scotland thanks to Dan Brennan's article in The Scotsman in 2008: https://www.scotsman.com/sport/argentine-football-returns-to-roots-of-its-scottish-founder-2474037

Scots Football Worldwide has a detailed account of Hutton and the other Scots who brought football to Argentina: https://www.scotsfootballworldwide.scot/argentina

In 2023 adidas launched the Argentum 1893 as the official ball in Argentina, in celebration of Hutton's legacy (pictured above). You can watch a short promo video here: https://x.com/GustavoYarroch/status/1691446667709390849

A memorial plaque, donated by the Argentina Football Association, is on display in the Scottish Football Museum: www.scottishfa.co.uk/news/the-scottish-trailblazer-who-paved-the-way-for-maradona-and-messi/

Alexander Watson Hutton is also commemorated on the Scottish Diaspora Tapestry: https://www.scottishdiasporatapestry.org/au03-alexander-watson-hutton/

RSS Feed

RSS Feed