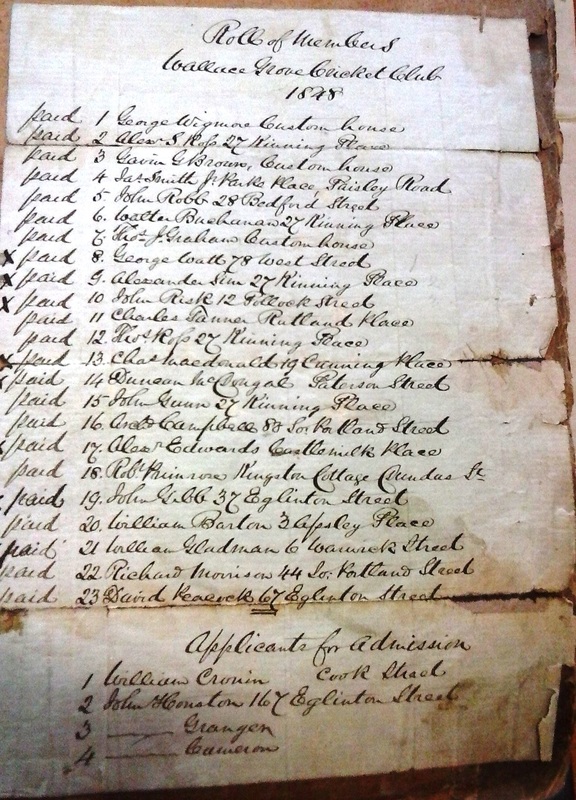

His scrapbook contains an extensive collection of early Scottish cricket material, including ephemera such as scorecards, tickets and posters from the 1850s onwards. There are even membership cards and fixtures lists from Clydesdale Football Club in the 1870s.

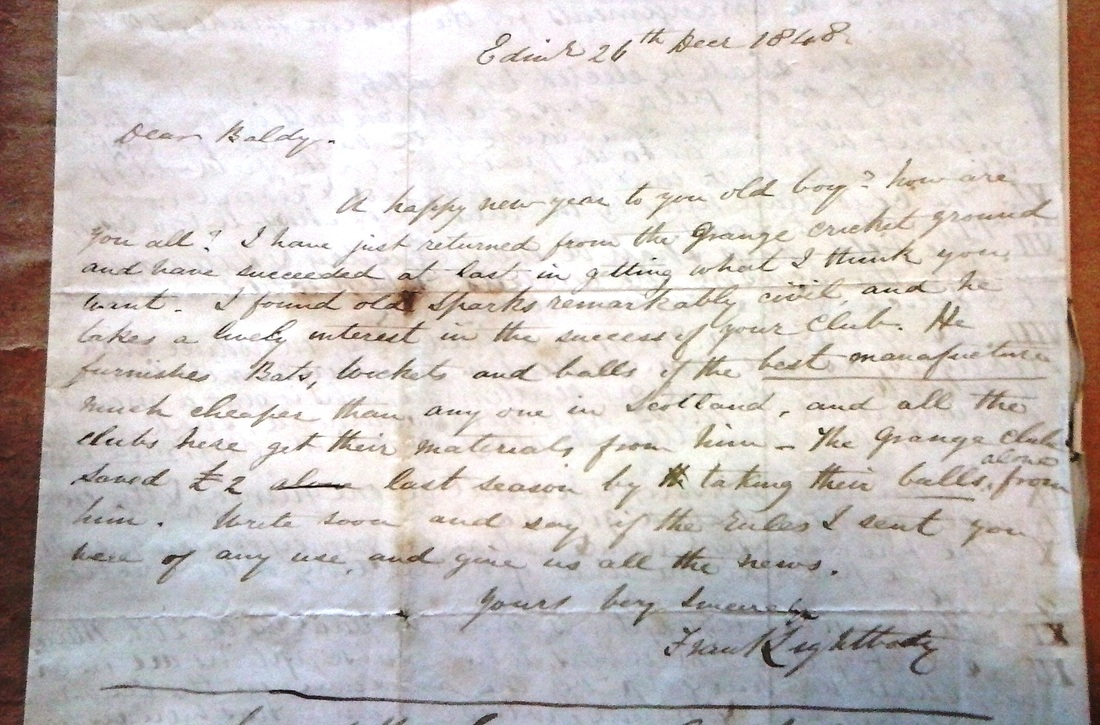

While there will be plenty of material for future articles, I've taken a closer look at the very first item, a letter which captures one of the challenges in setting up a cricket club. It is addressed to 'Dear Baldy' from a friend in Edinburgh who was able to give him some good advice on where to buy essential equipment.

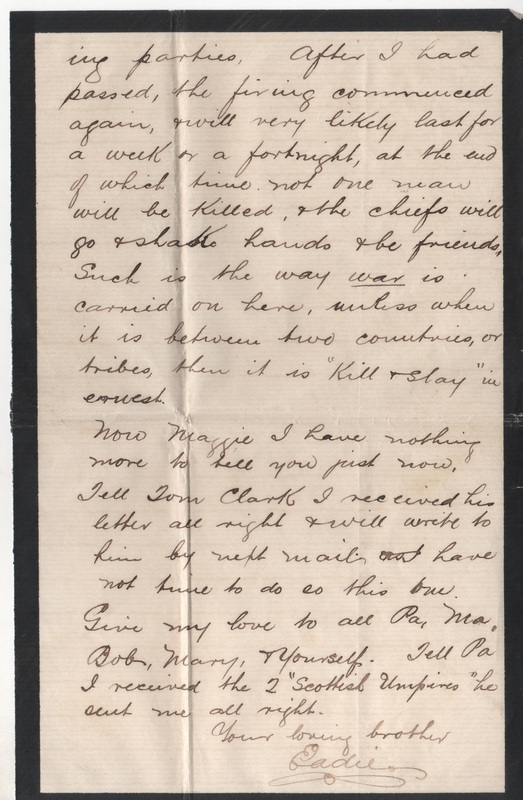

Dear Baldy,

A happy new year to you old boy! How are you all? I have just returned from the Grange cricket ground and have succeeded at last in getting what I think you want. I found old Sparks remarkably civil, and he takes a lively interest in the success of your club. He furnishes bats, wickets and balls of the best manufacture much cheaper than anyone in Scotland, and all the clubs here get their materials from him. The Grange club saved £2 last season by taking their balls alone from him. Write soon and say if the Rules I sent you were of any use, and give us all the news.

Yours very sincerely,

Frank Lightbody

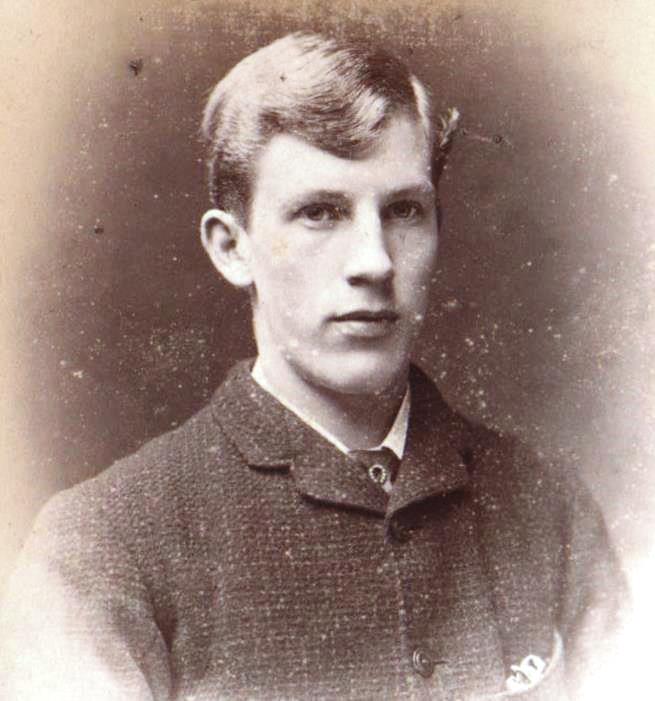

Lightbody (1824-1896) was a young civil engineer in Edinburgh, and although his personal connection to Campbell is not clear his advice was certainly useful. Which sent me off on a tangent - who was 'Old Sparks'? This turned into another story.

John Sparks has a unique place in Scottish sport as he was the country's first cricket professional. Born in Surrey in 1778 he had played many times for the MCC and was brought to Scotland in 1834 by the Grange Cricket Club (which was founded two years earlier). He was recruited by Edward Horsman, a Cambridge cricket blue who was studying for the bar in Edinburgh, who wrote to his friend James Moncrieff: "Try to get up a good field on Tuesday. I am going to bring down Sparks with me. He is the finest slow blower in England, and is exactly the style of practice our men want. I have made an agreement with him that he is to bowl all day, bowl in our games on practice days if required, stand umpire in matches, and do everything for £20, he paying his own expenses to and front Scotland."

Sparks had been a celebrated player in his younger days and was still able to bowl 'all day' as expressed in Horsman's letter. And he did so, often bowling five or six hours a day to members in practice, and when not bowling he was busy with his spade, levelling and repairing the turf. His style was 'slow round with much work from leg to off'.

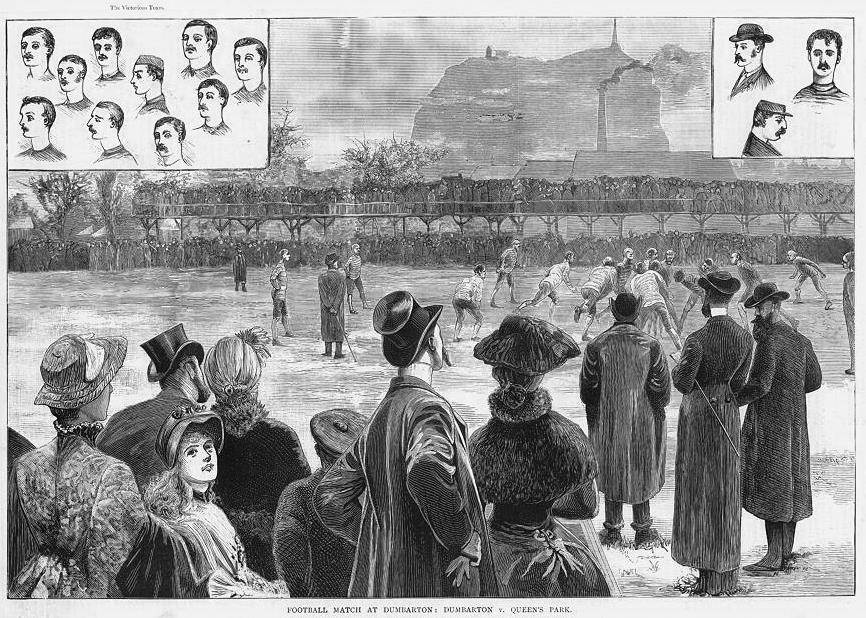

When Grange moved in 1836 to Grove Street, they gained possession of Scotland's first enclosed sports ground which allowed admission money to be charged (and helped keep out undesirables). John Sparks was installed in Grove Cottage, and as coach and groundsman he ran the show. It soon became known as Sparks's Cricket Ground.

His income was boosted by hiring out the ground: to celebrate Queen Victoria’s coronation in 1838 a grand cricket match was played there by the Holyrood and Caledonian clubs, while it was also used for sports as diverse as pigeon shooting, pedestrianism (1841) and football (1851). It was even a home for the schoolboys of Edinburgh Academy, who paid Sparks twopence each for the privilege of playing cricket on his ground.

Sparks is only recorded as playing in a couple of matches for Grange, and when his practice bowling began to fail with old age the club invested in a bowling machine, the 'catapulta', then a succession of English professionals. However, he remained in place until his death in 1854.

Sparks's Ground at Grove Street hosted the first international match, Eleven of England against Twenty-two of Scotland, in 1849. It remained the home of Grange CC until 1862 when the land was needed for city development, and the Fountain Brewery was built on the site.

Little else is known of John Sparks, but there are comments on his fearsome character. Records show he had a family as in the 1851 census he is living with a daughter and grand-daughter. He was secretive and would never reveal his age; an anecdote in a Grange CC history reveals that even on his deathbed, when his age was required by a doctor to get medicines from a charitable dispensary, the only answer he would give as "Say I am a hundred".

Links:

John Sparks cricket playing record

Archie Campbell, Hawick's forgotten sporting hero

Clydesdale Cricket Club archive references

RSS Feed

RSS Feed