Early in 1886, Reverend Alex Miller hurried to a Sydney hospital where he had heard a family friend from Scotland lay dying. He was too late. The young man called Eadie Fraser had already passed away, and the minister could only undertake the sad task of conducting the 25-year-old’s funeral, before writing to his family - news which took six weeks to arrive.

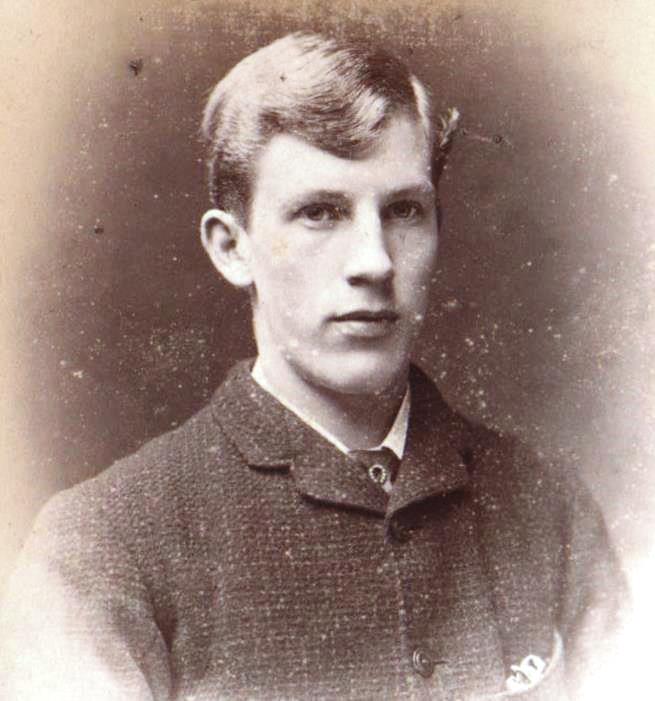

With this death in Australia, Scotland lost one of her most gifted footballers. The precocious talent known as ‘Graceful Eadie’ had broken into an exceptional Queen’s Park team as a teenager and won five Scotland caps along with two Scottish Cup medals. “His movements were perfect,” wrote the club historian. “His popularity was extraordinary. On the field and off it he was a thorough gentleman, and never descended to those tricks which tend to bring the game into disrepute.”

The recent rediscovery of Fraser’s personal diaries has shed new light on a short but extraordinary life that spanned four continents: born in Canada, he grew up in Scotland, went to work in Nigeria and died in Australia.

Born in 1860 to a deeply religious family in Ontario, where his father John (originally from Grantown-on-Spey) was a Presbyterian minister, he was named after Dr John Eadie, a professor of biblical literature. Two years later he came to Scotland when his father took charge of a congregation in the Gorbals.

Young Eadie started out in football with Kerland, a team in Crosshill, and at 18 was invited to join Queen’s Park. After making the Glasgow select team he won his first cap for Scotland against Wales in 1880 and further international honours followed as he enthralled spectators with his effortless dribbling down the left.

There was almost a party atmosphere on board the SS Benguela as a group of 18 young men headed for postings in the colonies, putting on light entertainments and playing deck games. Fraser was the only non-drinker which gave him at least one advantage on the voyage: “The chaps are all up and many of them are wishing they had been like me last night and they would have no headaches this morning.”

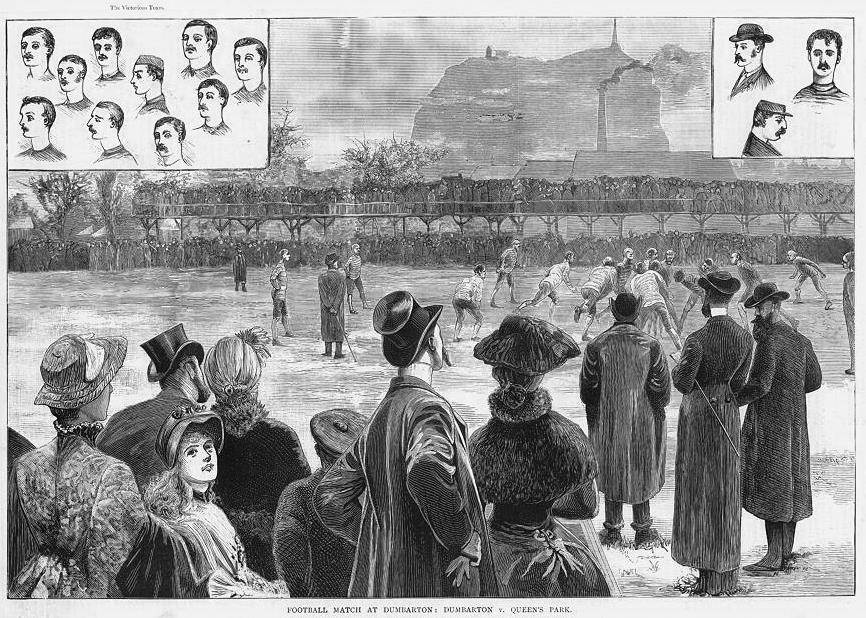

Stopping over on Madeira, he had a surprise encounter: “We were sitting on the roadside when two gentlemen on a bullock car passed us. I noticed one of them looked very hard at me. About a dozen yards further on the car stopped and the gentleman got out. He came back to us, and looking at me he asked “Is your name Fraser?” I felt astonished but said “It is”. “Is it Eadie Fraser?” he asked again. “Man, man, the last time I saw you was when your club the QP were playing against the Dumbarton at Boghead in the cup-tie last year”.”

Fraser’s first impressions were positive: “Opobo is a very nice place, indeed it is the prettiest and healthiest of all the rivers on the West Coast. There are five factories on the one side of the river, and ours is the only one on this side. I make the third white man in the employment. We have a splendid dwelling house – it is very airy and has a splendid veranda all around it. The food is very good. I have a black boy to wait on me alone. He works from 6 in the morning until 6 o’clock in the evening and we rest on Sunday.”

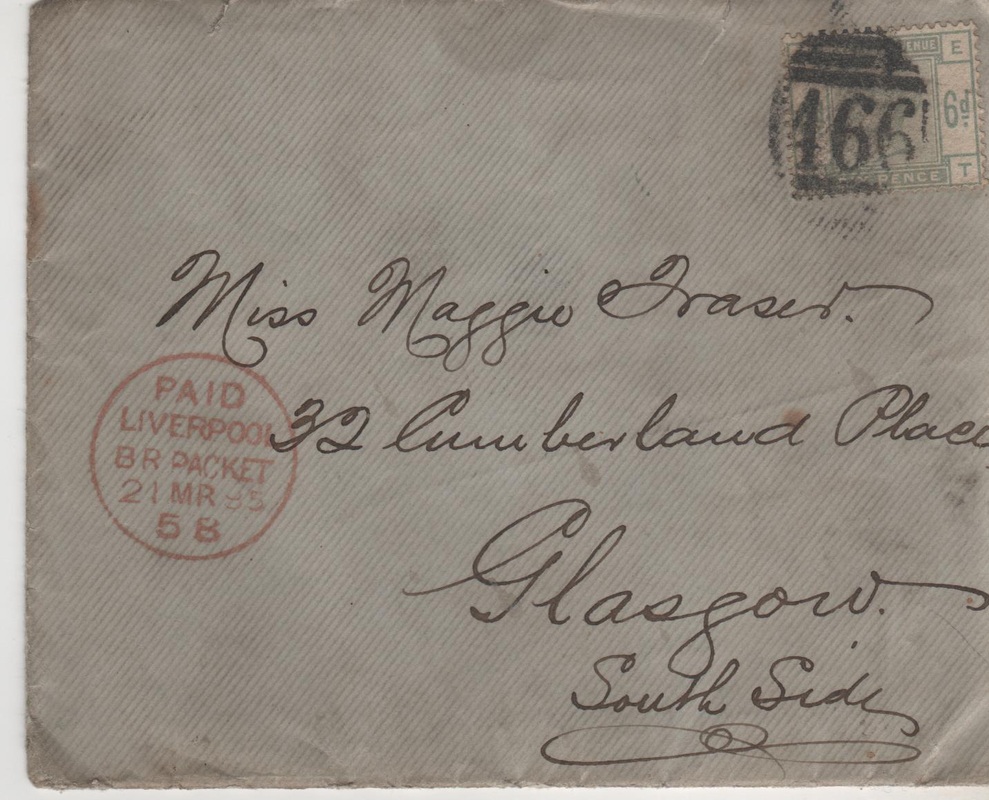

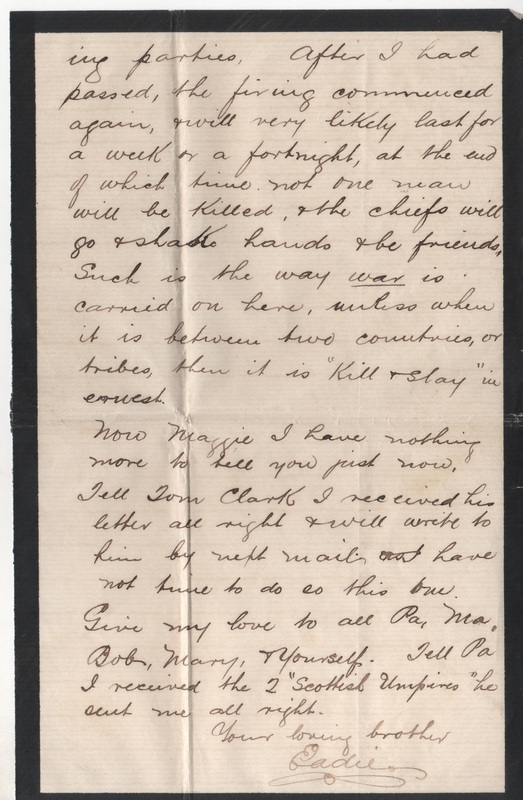

The first year went well, his father sent him copies of Scottish Umpire to keep him up to date with football news, and in a lively letter home early in 1885 he talked of hosting a successful visit from the firm’s agent, Captain Hooper, who was “awfully well pleased with us and the way the business has been carried out”.

Ominously, he also mentioned the oppressive heat reaching 130 degrees F (54C) and he soon fell seriously ill with tuberculosis, returning to Scotland to convalesce in a nursing home, before being advised to try the dry climate of Australia to effect a cure. Queen’s Park and Rangers played a benefit match to send him on his way and in September 1885 he bade a tearful farewell at Greenock, seen off by his brother Bob (who, although not so talented, would later win the Glasgow Cup with Queen’s Park).

In stark contrast to his African trip, the three month voyage to Australia was a desperate trial as his health went downhill. The sole paying passenger on the cargo ship Ardmore, Fraser was utterly miserable and after catching a chill he collapsed, coughing up blood, and spent much of the trip in delirium, confined to his bunk, getting bedsores as he could only lie on one side.

He was taken straight to hospital on arrival where, reviving briefly, he wrote what turned out to be his last letter home: “I hope to be all right in a couple of months. I am in the finest hospital in Sydney, best attention medical and nursing,” he said, but made it clear he was worried about finance: “I am paying £1 a week and I have only £8 altogether so I badly require money.”

Even on the other side of the world, Fraser was well known and was visited in hospital by David Walker, chairman of the Sydney YMCA and a keen footballer, who then summoned a Presbyterian minister, Alex Miller, who had studied divinity with one of Fraser’s Queen’s Park colleagues, WW Beveridge. He came too late, and Miller had the sad task of returning the young man’s belongings to his family.

Miller also set up an Eadie Fraser Memorial Fund in Sydney to pay for a headstone at his grave, but the appeal failed to gather sufficient funds from local footballers; even a request for a contribution from Queen’s Park fell on deaf ears. Sadly, his final resting place in the city’s vast Rookwood Cemetery remains unmarked.

Fraser’s African adventure and the struggles of the final voyage might have remained unknown had it not been for the rediscovery of his diaries and letters by his great great nephew Alex Cochrane. While some of the originals are too fragile to handle, they have been transcribed: “They were copied to my mother from a North American member of the extended Fraser clan,” he said. “The final letter is the most poignant with a description of the awful time he had.” Mr Cochrane, who lives in Glasgow, also has photos of Eadie alongside some of the Queen’s Park greats.

The diaries bring home the tragedy of a brief but much celebrated life, which one contemporary sports writer summed up: “I question very much if any forward of that time exercised such a potent influence over the spectators, and no style of play was more followed by the younger dribblers than that of Fraser.”

Malcolm John Eadie Fraser

Born 4 March 1860 at Goderich, Ontario

Died 8 January 1886 at Prince Alfred Hospital, Sydney

RSS Feed

RSS Feed