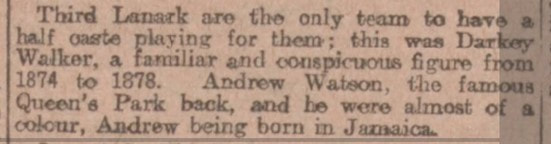

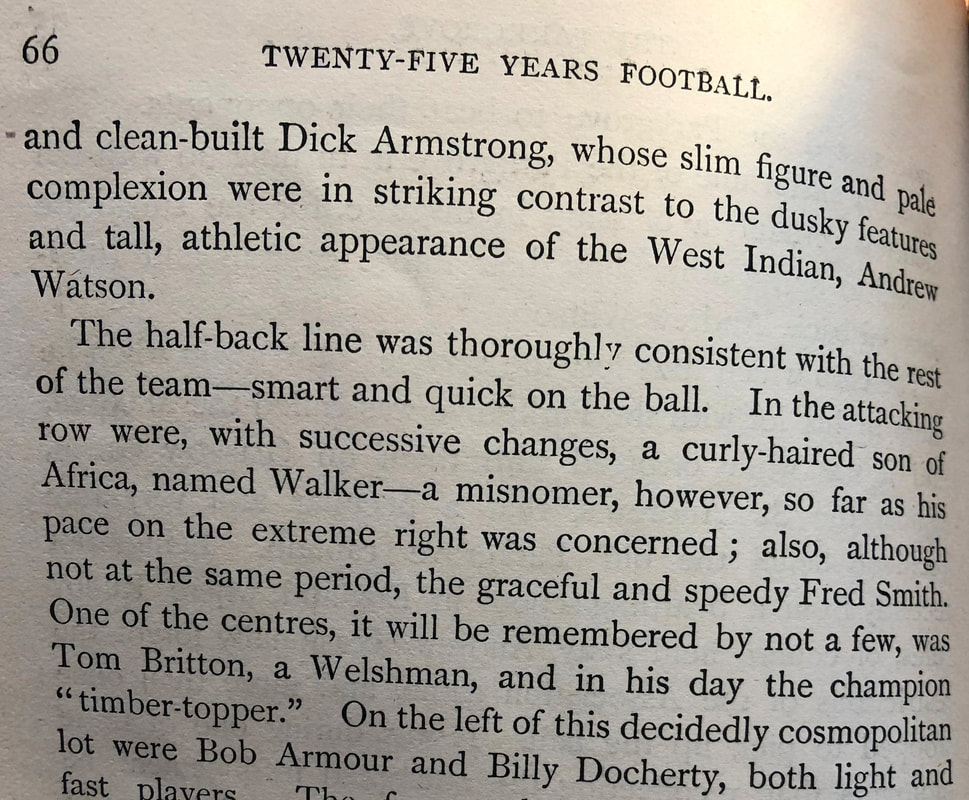

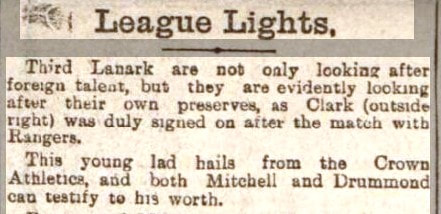

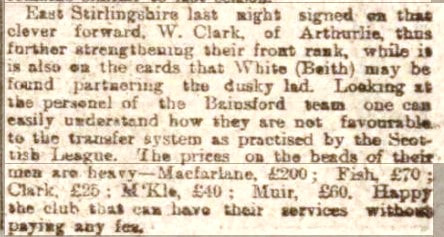

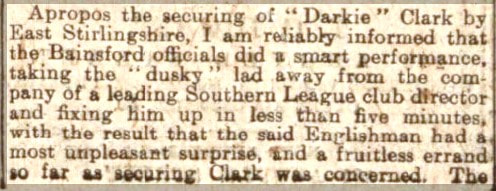

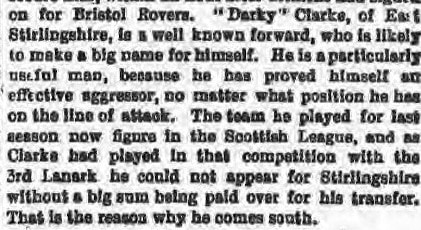

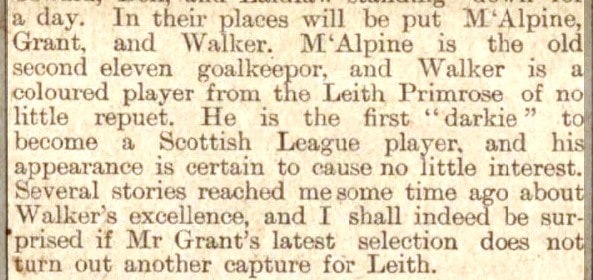

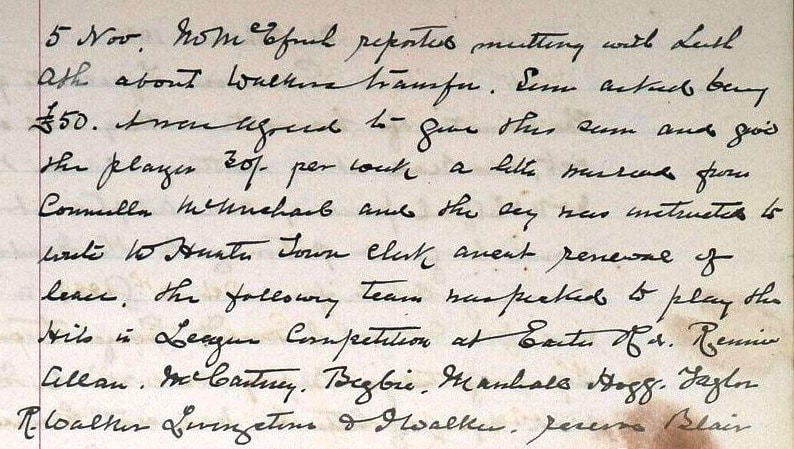

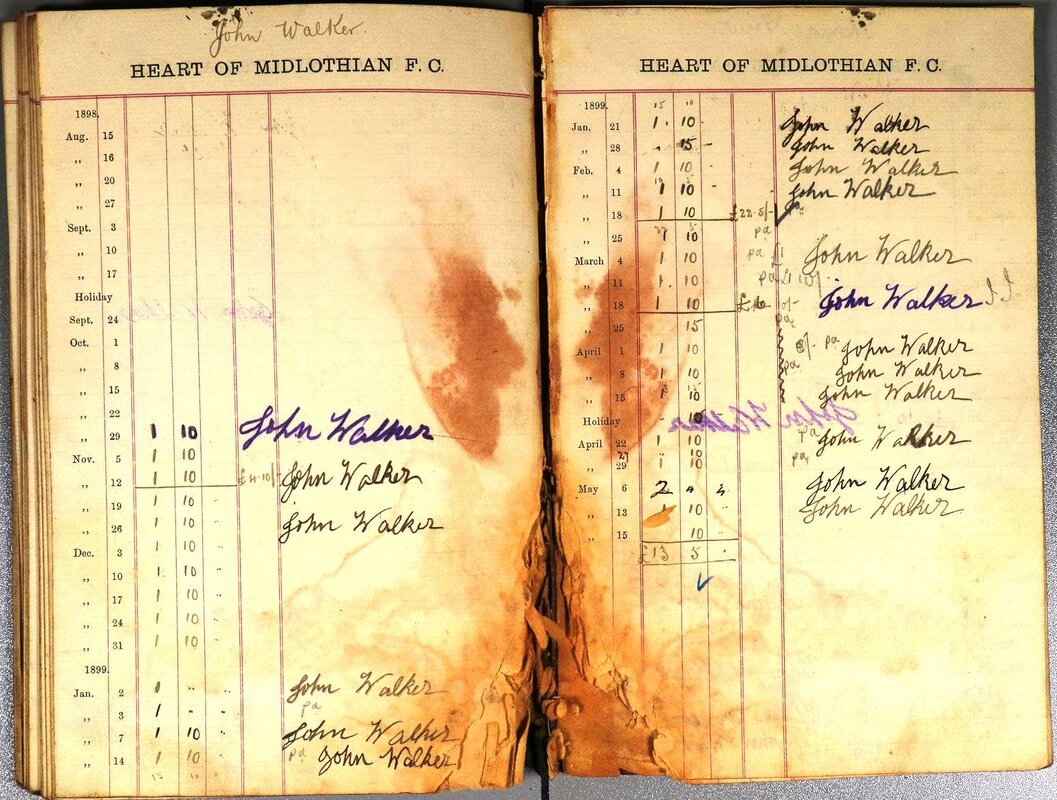

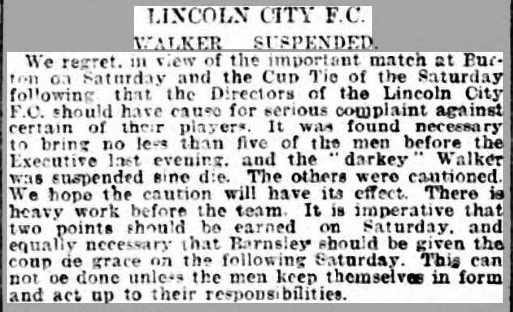

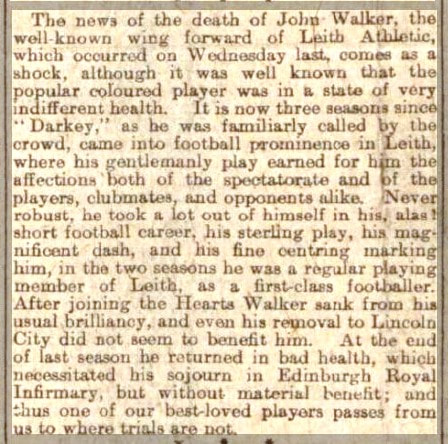

I have written recently about the early black pioneers of Scottish football, starting with Andrew Watson and Robert Walker in the 1870s, then Willie Clarke and John Walker at the turn of the century. It would be nice to think that their example inspired generations of other black footballers, and that their influence on the Scottish sporting scene was long-lasting. Yet the opposite was true: after Willie Clarke's departure for England in 1900, Scottish football closed in on itself.

A new book, Football's Black Pioneers, describes the challenging experiences of black players in England, and that has prompted me to research what happened in Scotland. I am going to take the story up to 1990.

Meanwhile, Dougie's half-brother and friend Peter Foley (same father, different mother) was carving out a career in the English lower leagues at Workington, where he was top scorer, then at Scunthorpe and Chesterfield. The story of how Dougie and Peter came to find out their shared paternity is astonishing.

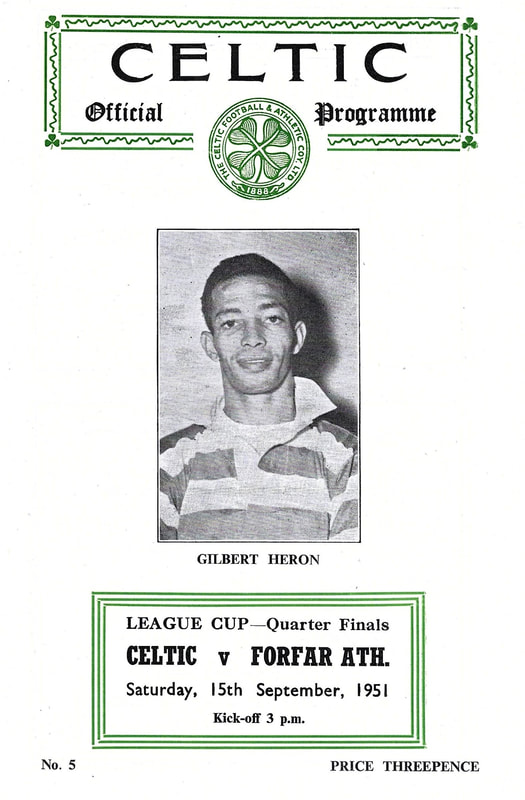

After that breakthrough, in the next two decades there were a few BAME (Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic) Scottish players, although nothing compared to the numbers in England.

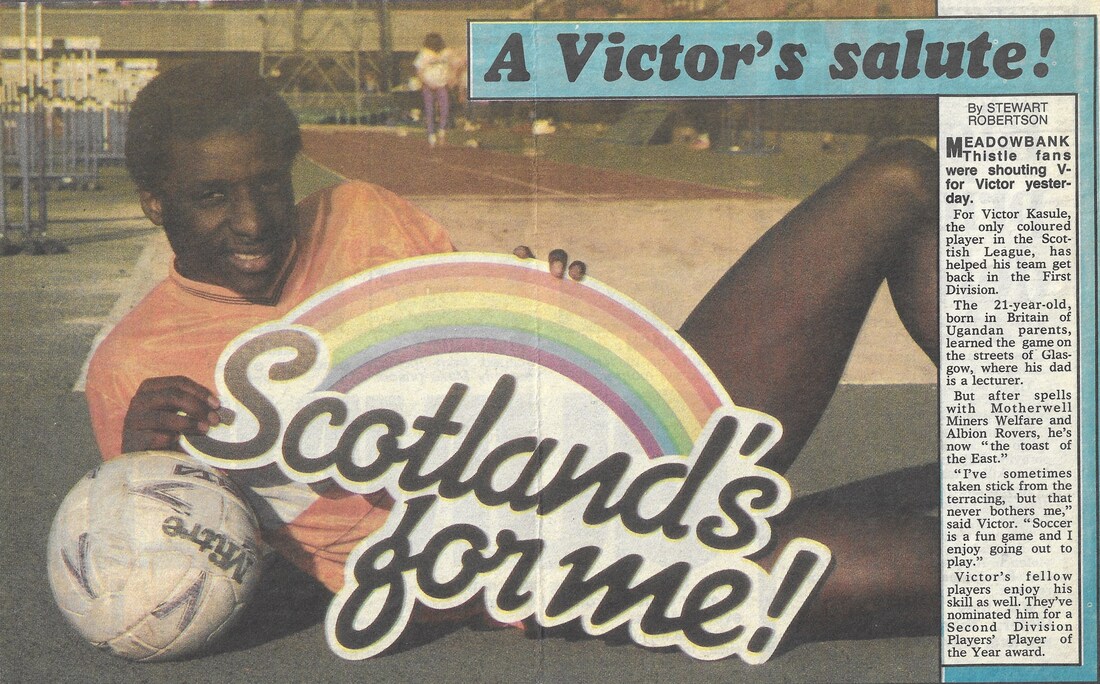

He was transferred to Meadowbank Thistle in 1987 for a club record fee of £28,000, helped them clinch the Second Division title and moved on the following season to Shrewsbury Town where his exploits off the field made a few headlines. He later played for Hamilton Academical and a few other clubs.

Also in the mid-1980s, Rashid Sarwar made 25 appearances for Kilmarnock and may have been the first Scot of Pakistani heritage to play professionally in Scotland. Mike McArthur played three first team games for Aberdeen in April 1988 and had a similarly brief spell at Kilmarnock.

And that was about that, as far as black Scots were concerned. In Emy Onuora's superb book Pitch Black he wrote about the English experience: 'The early pioneers had been largely looked upon as exotic embellishments to what had always been considered a white working-class game'. From a Scottish perspective, it is hard to disagree with his view.

Most black players seen in Scotland were in visiting teams, notably thanks to the new European Cup, such as Eugène N'Jo-Léa of St Etienne who featured on the front cover of the Rangers programme in 1957 and Paul Bonga Bonga of Standard Liège who played at Hearts the following year.

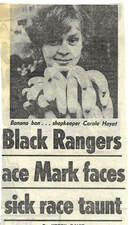

They were rarities, and while they generally provoked curiosity rather than abuse, Scotland could be a hostile place. Ruud Gullit recalled 'the saddest night of my life' in 1983 when he experienced racism as a footballer for the first time, in a UEFA Cup tie for Feyenoord at St Mirren. In 1985 the Commission for Racial Equality criticised Scotland supporters for barracking black England players at Hampden, while Rangers disparaged the 'appalling stupidity' of their own supporters for booing a black FC Twente player in a pre-season friendly.

Walters stuck at it and was soon followed by Raphael Meade at Dundee United, Paul Elliot at Celtic, Wes Reid and Gus Caesar at Airdrie, and Richard Cadette at Falkirk. With tedious regularity, all these black players were abused on and off the pitch and their treatment was sufficiently shocking to launch the first anti-racist movement in football, Supporters Campaign Against Racism in Football (SCARF). It began in Edinburgh and set out an action plan for football clubs to combat racism. In turn, this led to the formation of wider campaigns such as Kick it Out and Show Racism the Red Card.

Thirty years on, the game here is considerably more cosmopolitan and things have certainly improved, but Scottish football does not yet have a clean bill of health. There are still virtually no BAME referees, coaches and administrators, while abuse from fans still occasionally rears its ugly head. I hope this article helps people to understand where we have come from and why anti-racism campaigns are still necessary.

Players from elsewhere

Before Mark Walters arrived here in 1988, a number of black players from around the world made a fleeting acquaintance with the game in Scotland. I have listed them below, but I acknowledge this is a subject which is poorly recorded and there may well be others.

Three Egyptians played for Scottish clubs in the inter-war years, starting with Tewfik Abdullah at Cowdenbeath in 1922-23. Born in Cairo he played 6 league games and 2 Scottish Cup ties in a season interrupted by a broken arm. He had played for Egypt in the 1920 Olympic Games, joined Derby County, and after leaving Scotland went to Bridgend and various other clubs.

Mohammed Latif joined Rangers in 1934 after playing for Egypt in the World Cup but spent most his time with the reserves in the Scottish Alliance. He made a single league appearance against Hibs on 14 September 1935, as well as a friendly at Falkirk on 30 April 1936, then returned to the national team to compete in the 1936 Olympics.

Mohammed Abdul Salim, an Indian from Calcutta, played two reserve matches for Celtic in the Scottish Alliance in 1936, scoring a penalty in the second against Hamilton Accies. He attracted a lot of interest as he played in bandaged feet rather than wearing boots, but decided to return home where he resumed his career with Mohammedan Sporting Club.

During the war a young black striker called Fred Hanley, who had been on the books of Chelsea and Clapton Orient without making a first team appearance, was posted to Perth. He spent two seasons with junior side Jeanfield Swifts and made two appearances for Raith Rovers in March 1942 before heading to North Africa on active service.

Outside the senior leagues, the story of Biawa Makalaga, brought here as a child from Matabeleland and who played in goal for Rothes Victoria in the 1920s, deserves to be better known.

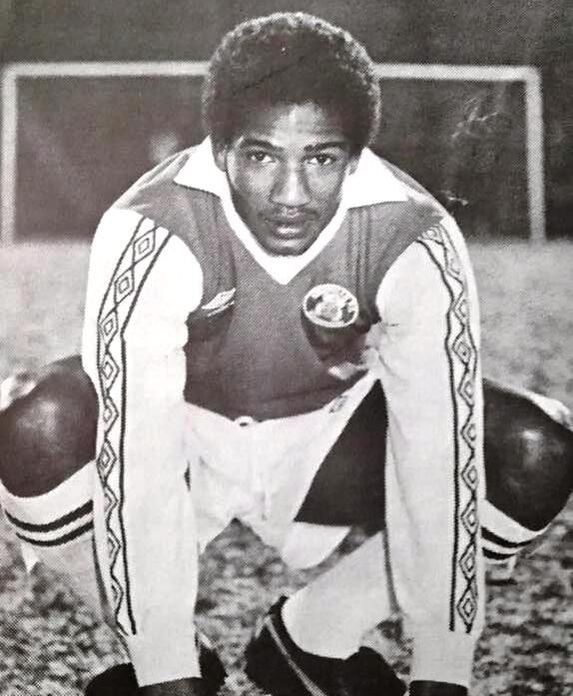

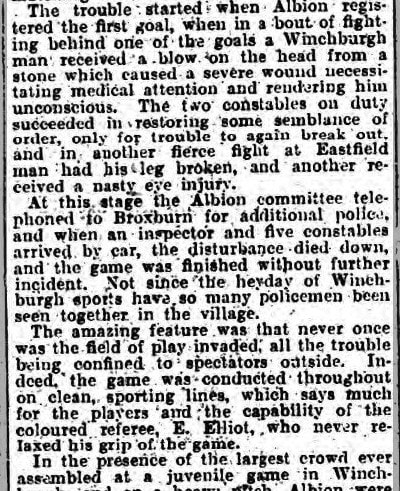

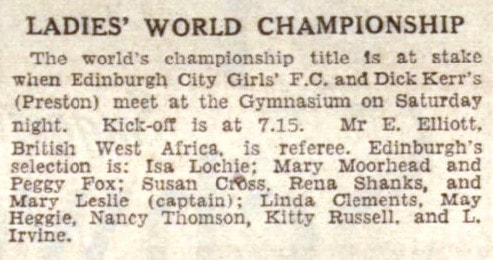

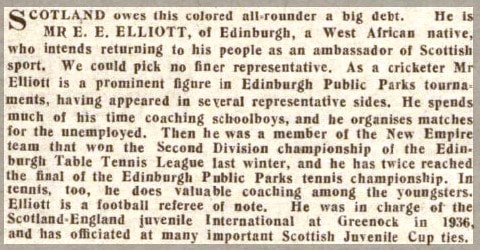

Also, referee Eustace Elliott from Sierra Leone took charge of non-league matches in and around Edinburgh, including a women's Championship of the World between Edinburgh City Girls and Dick Kerr's in 1939.

The only other significant instance of black players from abroad came in 1965, when Scottish football enjoyed a brief influx of Brazilians. There were eight in total.

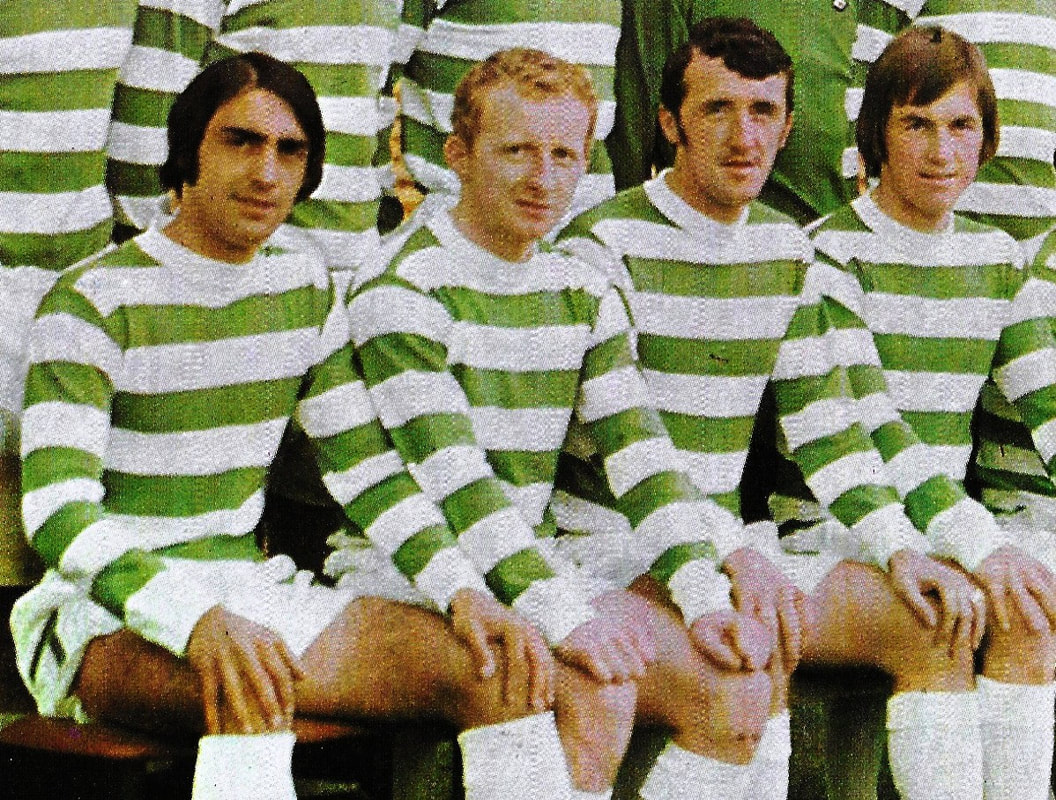

Celtic gave trials to Marco di Sousa and Airton Inacio, both of Sao Paolo, who played for the reserve team. Then Jorge Farah and Fernando Consol arrived, but all four were released in September.

Airton Inacio remained in Scotland after being released by Celtic and had a brief association with Dougie Johnson's Albion Rovers, scoring against Forfar Athletic on 29 September 1965 in his one match for them. He then left to play for Vitória Guimarães in Portugal and Stade Français in France but returned to these shores in the winter of 1967-68 and made three appearances for Clydebank.

Dunfermline also had two Brazilians but only one of them, Francisco 'Chico' Filho, played in a league match, against Morton on 18 September 1965. He went on to a fine coaching career in France and at Manchester United, where he worked alongside Sir Alex Ferguson – who had been his strike partner in the Dunfermline attack in 1965. Another trialist, Alexandre Gabrielle, was released and had a further unsuccessful trial for St Mirren in a friendly against Neilston.

Two other Brazilians went to St Mirren, where Fernando Azevedo (who was not black) played once against Morton on 11 September 1965 but left the following month and ended up in the USA. Roberto Faria played a trial for Saints alongside Azevedo in a Renfrewshire Cup semi-final.

My impression is that all these players found it hard to settle in Scotland, and were given few opportunities to adapt their game to 'the Scottish way'. With a bit more flexibility and understanding on the part of Scottish clubs, our game could have been so much different.

If you can add any further names to this article, please feel free to comment below, or contact me directly.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed