Three deaths, in different decades, and all relate to the same man: Claud Lambie, Scottish footballer. Twice his demise was mistakenly reported in the press, but there was no doubting the outcome when it finally came on a summer's night in 1921. He found a deserted spot on a suburban railway line and lay down in front of an approaching train to end his eventful life.

Lambie is best remembered as the man who transformed Burnley Football Club in 1890. He joined a club which was rock bottom of the Football League, banged in enough goals to lift them to respectability, and maintained an average of a goal a game over the next season. Then he left as suddenly as he came, because of issues with drink and discipline.

Born in Renfrewshire in 1867, Lambie and his family moved to Dennistoun in Glasgow’s east end when he was about 12. His first name was spelled Claud although it was widely reported with an 'e' at the end.

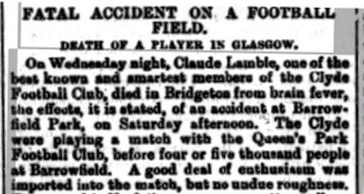

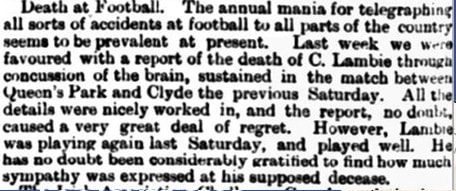

Where he started his football career is not clear, it may have been locally with Shettleston, but he suddenly found himself at the centre of national attention aged 19, after he played for Clyde against Queen's Park in November 1886. A collision with Welsh international Humphrey Jones left him winded but he picked himself up and played until the end of the match.

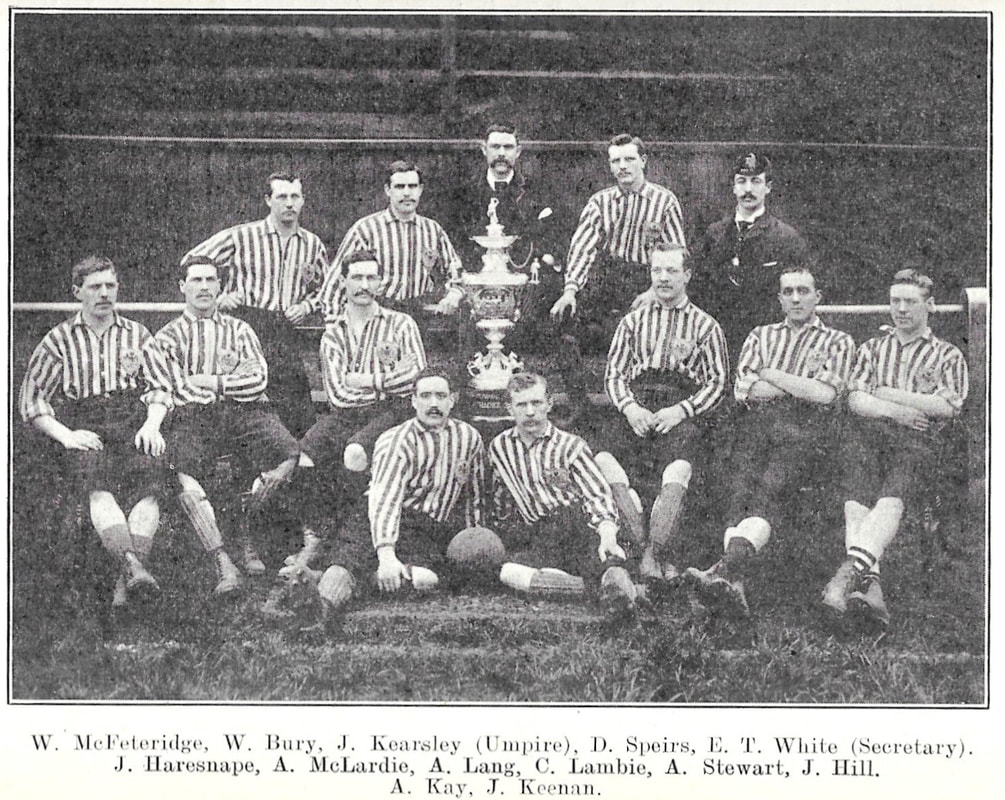

Over the next four years he developed into a capable centre forward as he moved around various clubs. From Clyde he probably had a year at Arthurlie and then played for Shettleston and Glasgow Thistle. Later biographies stated he was selected for Renfrewshire, his birth county, and that appears to have been in 1888 while he was at Arthurlie.

For all that Lambie was a decent player, it was something of a surprise when Burnley persuaded him to turn professional, but Burnley were desperate, having not won a single match all season. Their offer would have been hard to refuse, a signing fee of £40 on top of a wage of £2 10s a week, and in January 1890 he went south along with the Glasgow Thistle goalkeeper, Archie Kay.

Although it took a few weeks for Lambie to find his shooting boots at Turf Moor, on 1 March he hit the jackpot as Burnley hammered Bolton Wanderers 7-0 to win their first league game of the season. Lambie was the star of the show, scoring a hat trick, also having two goals disallowed and hitting the post. Burnley went on to win four games in a row and Lambie finished as the club's top scorer with eight goals in seven appearances.

It seemed Lambie could do no wrong as he was direct, forceful and just as good with his head as his feet, which earned him the nickname 'the Leap'. However, the summer of 1890 brought the first indication that all was not well with his personal life, as he was prosecuted before Burnley magistrates for drunkenness, although the case was ultimately dismissed.

In the new season he continued his fine form at centre forward, knocking in the goals for Burnley with three hat tricks along the way, but in October the club suspended him for a fortnight for 'misconduct'. And although he was top scorer, they did so again in March which caused him to miss the last three league games.

He went home to Glasgow where he took advantage of a Scottish FA amnesty for professionals (the game was still notionally amateur) and rejoined Clyde in time for their end of season fixtures. However, the press were not quick to notice that he was a shadow of his former self and Clyde's form in the 1891/92 season, with Lambie leading the attack, was utterly unpredictable. Incredibly, two league matches ended with a 10-3 scoreline: a thrashing of Vale of Leven in August and a humiliating defeat to Hearts in October. By then, Lambie was so far off the pace that Clyde showed him the door.

He next popped up in the unlikely setting of Auchterarder in Perthshire, where he played a county cup-tie for Vale of Ruthven. Back in Glasgow he joined Glasgow Wanderers, a short-lived side in the Scottish Federation, and also played a Scottish Cup tie for Cowlairs against Celtic in January. This brought the comment: 'He has been under a cloud for some time and when at last he emerged from obscurity he did not create a very favourable impression, on the contrary he was far too fleshy and palpably unfit. He scored all the same.'

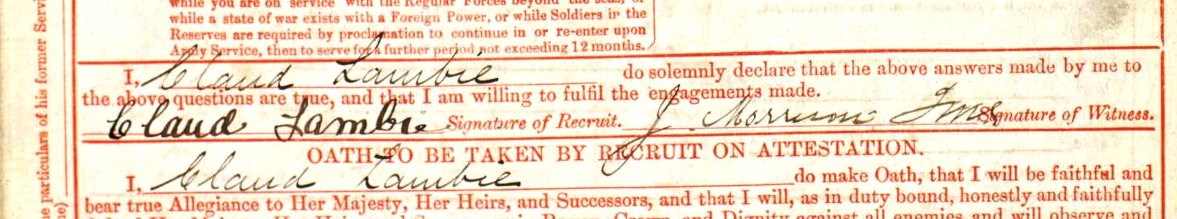

With his fitness and form having deserted him he took drastic action: in March 1892 he joined the Army, signing a seven year term for the Highland Light Infantry.

He played for them in the Army Cup and FA Cup and even represented the British Army against the London FA. Next time he went home on leave, at the end of 1894, he played once more for Clyde in a friendly.

His regiment was posted abroad to Malta early in 1895 and while there he won a medal when his team won the Governor’s Cup, although his old demons were still there as he was sentenced to a month in military prison for drunkenness. Next stop was Crete for six months in 1898 when the HLI were sent to help suppress an uprising, and he was released from the Army in March 1899 when his seven years were up.

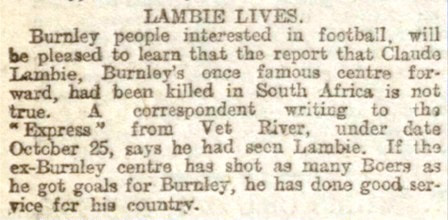

Like all former soldiers he went on the Reserve list and just a few months later after the South African War broke out he was recalled. He spent the next three years on active service, which entitled him to campaign medals with clasps; he also suffered another month in prison for being drunk.

When the war was over he was unscathed and came home to be discharged. Now a veteran, there was still time for a final piece of football action, playing for and coaching Auchterarder Thistle in 1902-03. Remarkably his team qualified for the Scottish Cup where they were drawn against Rangers, although he did not play in the 7-0 defeat at Ibrox.

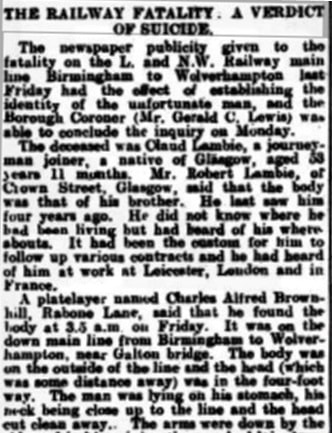

Settling back into mundane life as a joiner in Glasgow, he married Jessie McAlpine in 1904 but there were no children and she died ten years later. Distraught and alone, he went where the work was, and although his base was Glasgow there were frequent contracts south of the border.

So it was in 1921 he was working in the Midlands. He turned up at a Burnley match in Leicester, which prompted the Burnley Express to remind its readers what transformative player he had been. Then during the summer, who knows what his state of mind was, but 54-year-old Claud was now out of work and decided to end it all.

In the small hours of 22 July 1921 a railway guard reported a man walking on the main line from Birmingham to Wolverhampton. Then just after 3am a headless corpse was found near Galton Bridge in Smethwick; the head was some distance away.

Even thirty years on he was still fondly remembered as one of Burnley's greatest players and the papers paid fulsome tributes to his goalscoring exploits. Sadly, this time, there was to be no retraction of the news of Claud Lambie's death.

Claud Lambie

Born 30 July 1867 in Barrhead, Renfrewshire to William Lambie and Ann Dunipace

Died 22 July 1921 near Galton Bridge, Smethwick, Staffordshire

Football career

Shettleston 1885-86 (unconfirmed)

Clyde 1886-87

Arthurlie 1887-88

Shettleston 1888-89

Glasgow Thistle 1889-90

Burnley Jan 1890-March 1891

Clyde May-Oct 1891

Vale of Ruthven Nov 1891

Glasgow Wanderers Dec 1891-Feb 1892

Cowlairs Jan 1892 (Scottish Cup tie)

Highland Light Infantry 1892-1902

Burnley Dec 1892 (four matches)

Clyde Dec 1894 (one match)

Auchterarder Thistle 1902-03

Honours

Renfrewshire v Dunbartonshire, 1888

British Army v London, 1894

Governor's Challenge Cup (Malta), 1896

NB there are references in the press to appearances for other representative teams including Renfrewshire, Glasgow and even reserve for Scotland but I have been unable to substantiate these.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed