At a time when society was overwhelmingly white, the team from Govan had no less than three ethnic minority players: Andrew Watson and Robert Walker who were black, and a goalkeeper of Asian heritage called Tommy Marten.

His existence was highlighted in 25 Years Football, which was published in 1896 by the former Rangers player Archie Steel, writing under the pseudonym 'Old International'. He described his book as 'the most authentic and exhaustive treatise on football ever written', and his little paperback is indeed an invaluable resource with anecdotes of many clubs and players from the early years of Scottish football.

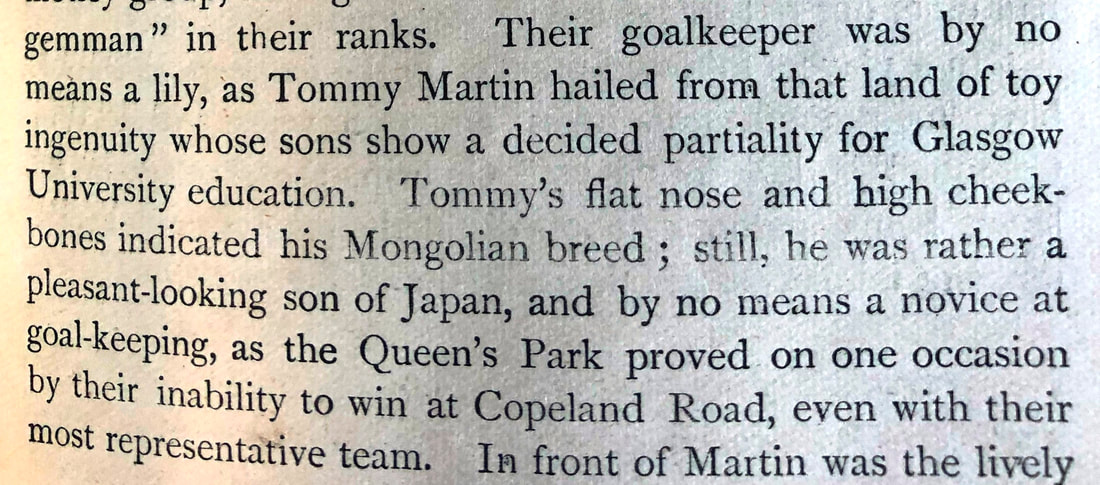

Steel, who played against Parkgrove in a Scottish Cup tie in 1878, also said: 'Their goalkeeper was by no means a lily, as Tommy Martin hailed from that land of toy ingenuity whose sons show a decided partiality for Glasgow University education. Tommy's flat nose and high cheek-bones indicated his Mongolian breed; still, he was rather a pleasant-looking son of Japan, and by no means a novice at goalkeeping.'

The historian Richard McBrearty, of the Scottish Football Museum, first highlighted the importance of the Parkgrove trio in an article for Show Racism the Red Card.

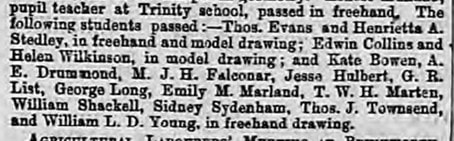

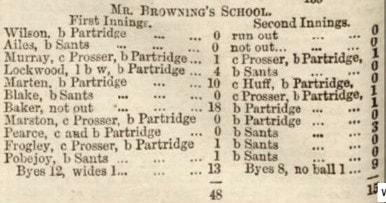

That inspired me to researched the background to Tommy Marten's life. It soon became apparent that Archie Steel's paragraph, although interesting, is somewhat misleading. He spells his surname wrong, he was not from Japan, and nobody called Thomas Marten (or Martin) matriculated at Glasgow University.

Here, for the first time, is his story.

Thomas William Henry Marten was born in 1857 in Surakarta, a town in Java which was then part of the Dutch East Indies, now in Indonesia. His parents were an English shipping merchant called Elliott John Marten and his ethnic Chinese partner Oeij Sieuw Nio, who were unmarried at the time although they did eventually tie the knot in 1877. The wider Marten family had extensive shipping interests in the area.

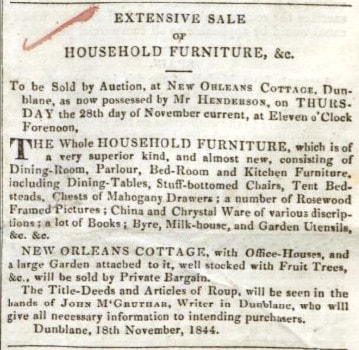

Another reason for him coming to Scotland as a young adult could have been his family links: his uncle William Marten, who was also in business in Java, had married Elizabeth Rodger of a well-known Glasgow shipping family with strong links to the China trade. It would have made sense for Tommy to start his career in a family firm.

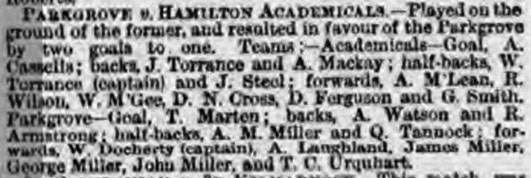

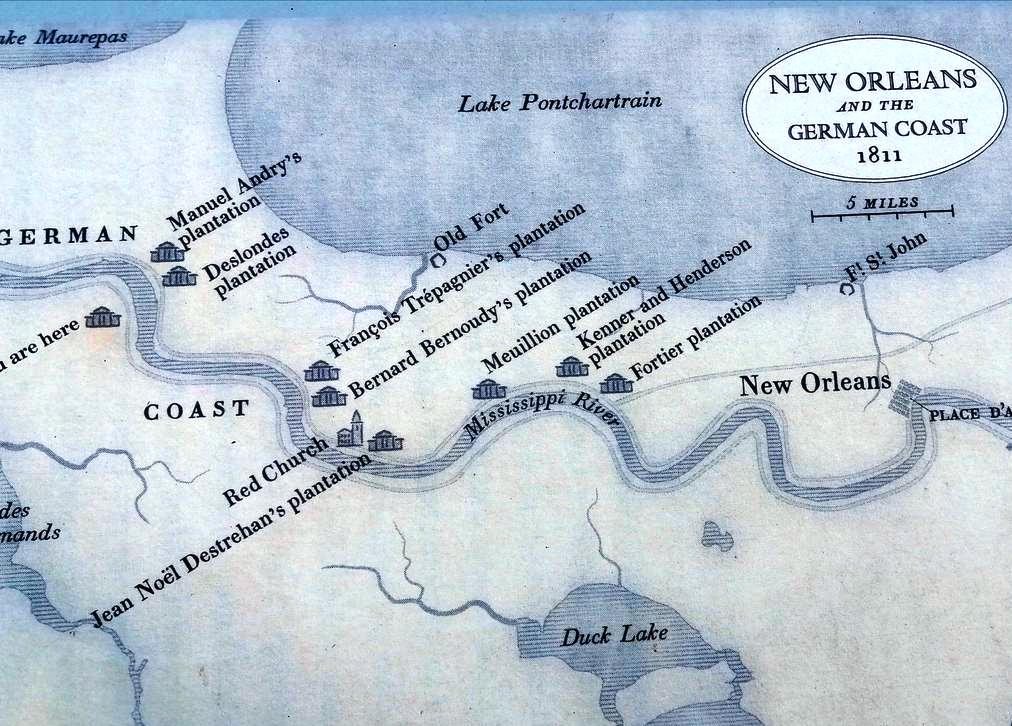

The earliest mention of him playing football was for Parkgrove against Hamilton Accies in October 1876, when he kept goal in a team which was led by Andrew Watson.

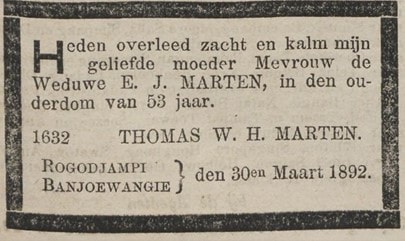

He appears to have spent the rest of his life based in the town of Banyuwangi (also spelled Banjoewangie) on the east coast of Java, where he was a successful commercial and shipping agent, at one point running the ferry service to Bali. He never married and died in 1911, aged 55.

The three association footballers at Parkgrove were emulated in that decade by prominent rugby players Alfie Clunies-Ross (mother from Malaya) and James Robertson (mother from Gambia). However, although those pioneer footballers were able to play in Scotland without any obvious discrimination due to their colour, nobody followed in their footsteps.

It is a long story, but after Andrew Watson's departure in the 1880s Scottish football had an almost complete dearth of BAME players for generations. Apart from the brief appearances of Willie Clarke and John Walker at the turn of the century, Scotland's next homegrown black footballer was Dougie Johnson at Brechin City in 1964 and it is a sad fact that there were more BAME players in Scotland in the 1870s than in the 1970s.

This makes it all the more important to recognise the coming together of Tommy Marten, Andrew Watson and Robert Walker at Parkgrove FC, and celebrate Scotland’s first multi-racial sporting club.

Thomas William Henry Marten

Born 19 February 1857 in Surakarta, Central Java.

Died December 1911 in Banyuwangi, East Java.

NB as he lived in a Dutch colony, his name is also recorded as Thomas Willem Henri Marten.

I have not been able to track down a photograph of Tommy Marten, and would be delighted if someone could find one!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed