by Andy Mitchell

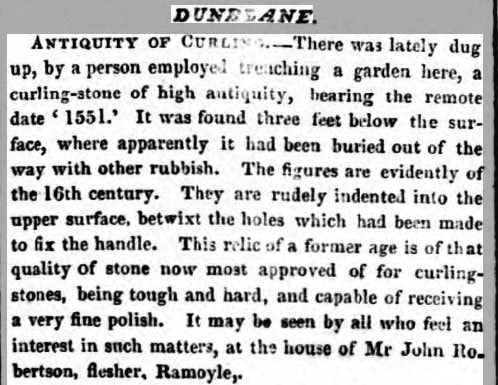

When I was researching a talk on the history of sport in Dunblane, I came across the story of an ancient curling stone which was found in 1834. Buried in a cottage garden on the outskirts of town, it was inscribed with the year 1551 and was claimed to be the oldest stone in existence.

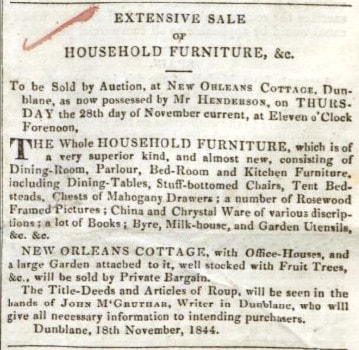

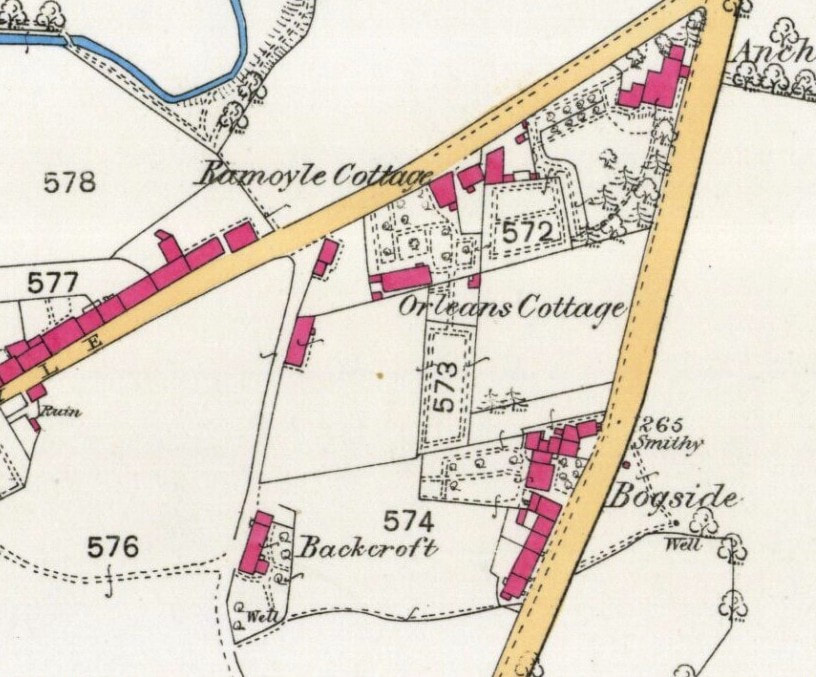

The stone's age was later trumped by an even older example found in Stirling, and in any case it has since disappeared. It could have been merely a footnote in the town's sporting heritage but what intrigued me was the name of the property where it was discovered: New Orleans Cottage. Why on earth would someone in Dunblane call their home after a city in the deep south of America?

My search for the answer revealed a shameful link to the American slave trade, as well as a bitter legal battle for the fortune that was amassed on the back of human misery.

After Patrick died there in 1811 his family - wife Janet, son Thomas and daughter Jean - returned to Scotland where his widow remarried to John Maiklem, a former soldier now working as a weaver in Stirling.

When Thomas grew up he bought a piece of land and built his cottage in Ramoyle, a small community on the edge of Dunblane. He could afford it because he had a rich uncle in America, his father's younger brother.

Quite how rich his uncle Stephen was became clear when he died in New Orleans in 1838. He had somehow accumulated a fortune that was reported to be worth £318,750, the equivalent of upwards of £30 million in today's money.

We sometimes have a conceit of ourselves in Scotland that the people who profited from slavery were the rich and powerful, the tobacco lords and sugar aristocracy, nothing to do with the common folk. Yet Stephen Henderson was a humble mason's son from Dunblane.

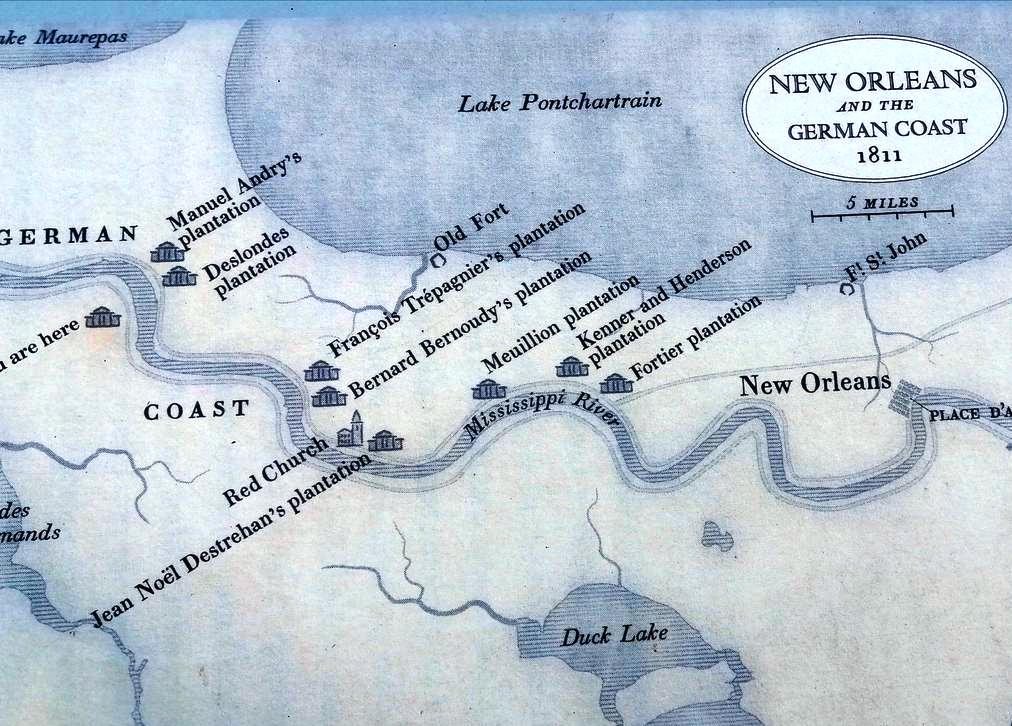

Born in 1773, he had crossed the Atlantic to seek his fortune in the New World where, after a while, he joined forces with a man called William Kenner. They set up a trading company based in New Orleans and their firm of Kenner, Henderson & Co bought cotton and sugar from the Louisiana estates and shipped it to Liverpool, while for the return journeys they imported English and European goods to sell in local stores. Henderson was an astute businessman and became known locally as 'Monsieur Croesus' and 'the Scottish Marvel'.

But that was not all he bought and sold. Behind those accolades the Scot had a dark mercenary attitude that exploited the laws on slavery. The direct importation of foreign slaves into Louisiana was outlawed early in the 1800s but it remained legal to bring slaves from elsewhere in the United States, a loophole which meant that slaves could still be transported and sold internally. Many were shipped from South Carolina to Louisiana to meet the plantations' insatiable demand for labour.

The Kenner & Henderson sign announced their 'showroom' in New Orleans where planters could buy anything from building materials to human life. The slaves were packed into pens to await a purchaser, and for example in June 1806 the firm advertised the sale of 74 'prime slaves of the Fantee nation' (modern day Ghana) who had been brought from Charleston on board the schooner William, while in October that year they sold 66 'prime young slaves of the Congo nation' brought on the Carolina.

Prices were inflated because of the legal restrictions and a single adult male slave might sell for upwards of $600. The slave market profits were enormous but so was the potential for misery, as while the slaves enriched their owners they were often treated appallingly. Conditions on the sugar cane estates which lined the Mississippi were known to be so brutal that slaves spoke with dread of being 'sold down the river', a phrase which resonates to this day.

Meanwhile Henderson continued to prosper and was already a very wealthy man when he took a step towards respectability in 1815 by marrying Zelia Destrehan, the daughter of a prominent plantation owner. Soon, he acquired her father's estate at Destrehan, which he added to his portfolio of properties, including estates in Louisiana (Elm Park, Forest and a half share of Mount Houmas) and elegant mansions in Virginia and New Orleans.

Then, in a dying man’s crude attempt to rewrite history, he stated: 'I have always trusted my blacks with much indulgence and even personal kindness. I have always been opposed to slavery.' Essentially he claimed he had only gone along with it to fit in, ensuring that his own slaves were well treated. He specified that his slaves should be freed after his death and sent to Liberia, but there was a significant catch: most of them had to wait 25 years for their liberty.

The truth is that Henderson left a legacy of misery: his 'property' included hundreds of slaves, while his money derived not just from their labour but from the profits of buying and selling their lives.

He left detailed instructions about what was to happen to his money, scattering it with largesse, although he found space to slander his parents: 'My whole family may be considered as drunkards, and this misfortune must have come upon the side of my father; although that he was an antiquarian, learned and intelligent, to get drunk once a month was to him a jubilee. My mother was a Drummond, good natured but without much capacity. They were profligate and indolent; being poor, they were always in bankruptcy.'

He showed he had not forgotten his roots as he wanted his home town to benefit from a large legacy. He allocated two thousand dollars a year to go to the poor of Dunblane, to be administered by the resident minister of the Presbyterian Church and the two highest civil officers of the town. He also left two thousand dollars a year for ten years for the erection of a school house in Dunblane and for the education of the poor. 'I feel no obligation for these acts of charity; it is only done to help the poor who like myself may be thrown upon the world without a penny or a friend,' he wrote.

Even at the exchange rate of about five dollars to the pound, this money would have transformed many lives in what was then a poor community, described by a contemporary visitor as 'Dirty Dunblane'. But the money never came.

However, Rost stood to be a significant beneficiary of the will, having also married into the Destrehan family, and he had taken over the Destrehan estate (and its slaves) following Henderson's death. Conveniently, John Grierson died in 1840 so his story could not be contradicted; then a court in Louisiana ruled that Henderson was of unsound mind when he made his bequests, and that the money should go to his wider family instead, including nieces and nephews on both sides of the Atlantic.

That might have been the end of it as far as Dunblane was concerned, until a court case in Scotland in 1842 revealed some of the sums at stake. John Maiklem, step-father of Thomas Henderson and his sister Jean, successfully sued for ten per cent of their bequest from their late uncle. The case revealed that Thomas and Jean had already received £4,875, and were due a further £2,600, the equivalent of well over half a million pounds today.

This alerted James Boe, the new minister in Dunblane, who together with the Sheriff Substitute launched a legal bid to unlock a substantial windfall for the people of the town. They appear to have had no knowledge of (or had no qualms about) the slavery origins of the money.

It was a complicated case, fought at every step by the Henderson relatives, and the wheels of justice moved so slowly that a final decision was not reached by the Court of Session until 1862. By a majority, Scotlands law lords ruled against the Dunblane claim, which ended the matter.

The bulk of the legacy appears to have remained in Louisiana, claimed by the extended family of Henderson relatives, although they would likely have lost it in the American civil war.

Today, Stephen Henderson's role in promoting and profiting from slavery has been airbrushed in a kind of collective amnesia. An epitaph on a grand churchyard memorial near New Orleans talks of his 'moral worth' and claims that he passed through life with 'an unblemished character'. His old estate at Destrehan, which was used to shoot scenes for the film 12 Years a Slave, is now a tourist attraction which focuses largely on the lifestyle of the white planters although it does make an effort to interpret the slave experience. Another of his grand houses at White Sulphur Springs in Virginia is part of the Greenbrier luxury resort, known as the President's Cottage after it was stayed in by several US Presidents.

There are no known portraits of Stephen but he did leave a little-known memorial in Dunblane Cathedral. His 'profligate and indolent' parents were originally buried in the kirkyard but in 1831 he paid for them to be disinterred and reburied in crypts below the medieval building. Two large stone slabs on the floor, hidden underneath the carved oak pews, mark their final resting place.

One wonders how life for the people of Dunblane might have been transformed if Henderson's legacy had been spent in the way he intended. Perhaps it is better, after all, that the town was untainted by the profits of the untold misery he inflicted on thousands of his fellow human beings.

NB Dunblane Cathedral also has a memorial to William McCowan, a local man who opposed slavery and signed up to fight for the Union in the American Civil War. It is the tallest monument in the cathedral graveyard. You can read the article I wrote about William McCowan here.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed