Two of them featured former players George Sinclair and Paddy Crossan, which adds an extra dimension to the interest of the booklet. Much could be, and has been, written about the relationship between football and alcohol, but it is fascinating how many players went into the pub trade, perhaps using a testimonial pay-off to set themselves up.

|

When I recently digitised the 1928 Hearts booklet Tales from Tynecastle (now available for download on my Sporting Anthology page), I was intrigued by some of the adverts.

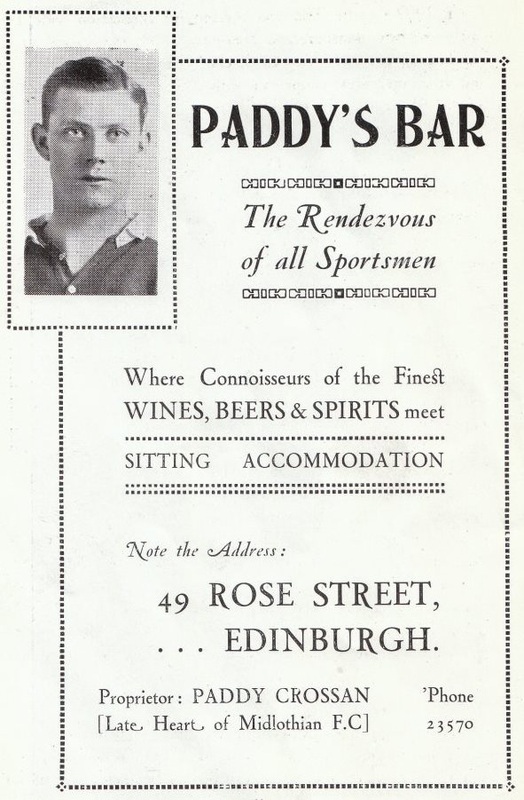

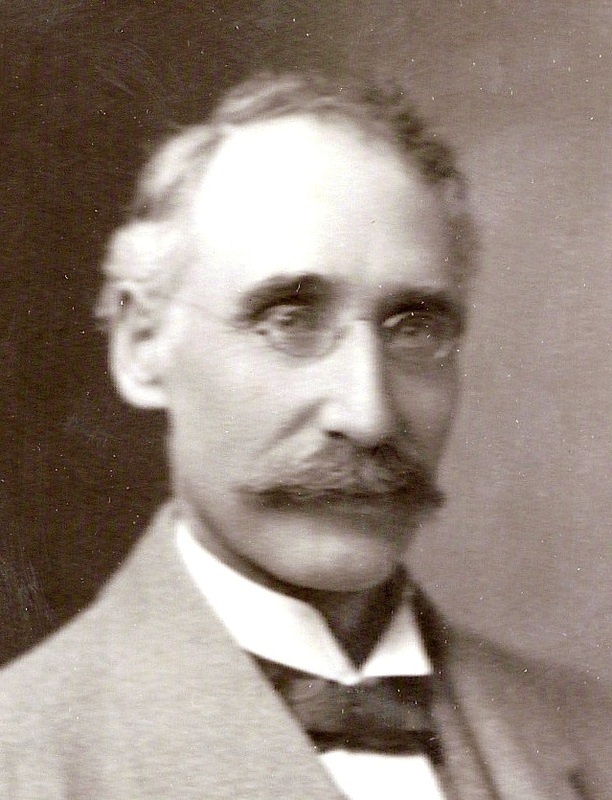

Two of them featured former players George Sinclair and Paddy Crossan, which adds an extra dimension to the interest of the booklet. Much could be, and has been, written about the relationship between football and alcohol, but it is fascinating how many players went into the pub trade, perhaps using a testimonial pay-off to set themselves up. Paddy's Bar felt obliged to advertise that it offered 'sitting accommodation' for 'connoisseurs of the finest wines, beers and spirits' which is probably a reflection of how basic some pubs could be in the 1920s. It remained an institution in Rose Street long after the player died in 1933, in fact until recent living memory, but has since changed identity a few times and is now the Black Rose. Sinclair made a surprising choice of location for a Hearts player, as Montrose Terrace is at the top of Easter Road, but promised his customers 'prompt attention, excellent quality and civility' with Dryburgh's Starbright Ale always in the best of condition. It was obviously a good business as he kept it until his death in 1959. The bar retained his name to about the end of the century but now it is a rather douce coffee and deli bar called Just the Ticket.

2 Comments

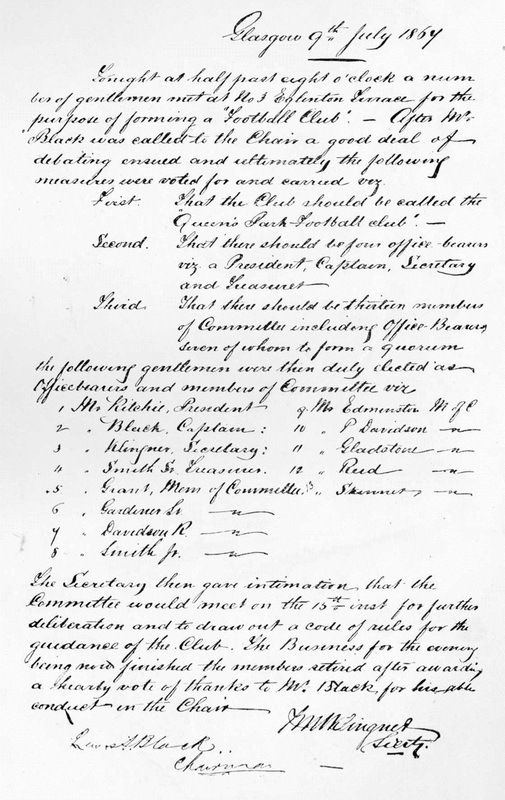

It's a crucial part of our sporting legacy, but hardly anyone knows where it is. On 9 July 1867 a group of men met at 3 Eglinton Terrace on the south side of Glasgow 'for the purpose of forming a Football Club'.

Scotland's first association football club duly came into being, named Queen's Park after the nearby recreation ground where they played. The club became an institution that almost single-handedly introduced the association game to the city, organised the first international match in 1872 and provoked the formation of the Scottish FA the following year. The story of the club is well known, but what about the location of this historic meeting? It is a puzzle that is hard to answer satisfactorily as Eglinton Terrace no longer exists: it disappeared as an address in 1891 when its parent street, Victoria Road, was absorbed into the city of Glasgow and renumbered as one long thoroughfare. The site is now occupied by four-storey tenements, which Historic Scotland considers to be sufficiently important in architectural terms to be worth listing Grade B. They date the tenements to the 1880s, but the buildings are somewhat older as Victoria Road was first laid out in the late 1850s, linking the city with the open spaces to the south, including the new Queen's Park. Eglinton Terrace started to be built in 1864, a terrace of tenements on the west side of Victoria Road, running south from Allison Street to Prince Edward Street. Press adverts indicate the original properties were self-contained flats, with shops at street level. The first notice appeared in the Glasgow Herald in March 1864: 'To Let, at Eglinton Terrace, houses of 3 and 4 rooms and kitchen, bathrooms &c, with garden plots if required.' This was bigger than many people required, and some of the residents took in lodgers; Mrs Cook of 3 Eglinton Terrace advertised 'Two young men may have share parlour and bed room'. A few of the tenants at Number 3 can be identified from Glasgow street directories, including a bookseller and an accountant, although none of them appear to be founders of Queen's Park FC. One of the earliest residents, listed in the valuation rolls from 1865, was a wine and spirit dealer called James Cook at No 1. His pub was on the corner with Allison Street, and it has been suggested that it had a meeting room at No 3. Certainly, there are reports of later meetings taking place in James Whyte's, as the pub was later called before being transformed into the art deco Victoria Bar at the turn of the century. It seems unlikely that a pub would extend two doors along, but James Cook and his wife Jane, referred to above, owned a flat at Number 3 so potentially they had the space to host a meeting in their home over the pub. So why did the Queen's Park founders chose to meet in this particular property? A potential clue comes from an advert in the Glasgow Herald on 8 July 1867, just one day before the meeting: 'To Let at 3 Eglinton Terrace, Victoria Road, Parlour and Bed Room. Plunge and shower bath in house.' Would that vacant parlour have had enough room for 20 people to gather? While the definitive answer to that question will probably never be known, the precise location of 3 Eglinton Terrace can be pinpointed to what is now the tenement entrance at 404 Victoria Road, between the Victoria Bar which occupies 400-402 and Optical Express at 406-408. A close examination of the Glasgow street directories shows clearly the evolution of Eglinton Terrace and its residents up to the 1890s. This unremarkable suburban tenement is the location for the foundation of Scotland’s first association football club, and is therefore of great significance for our sporting heritage. At present, however, there is nothing to mark the spot. Commemorative plaque, anyone?  Since Andy Murray's amazing victory at Wimbledon, there has been much comment about him being the first Scots-born men's singles winner since Harold Mahony in 1896. But Mahony's birth in Edinburgh was almost an accident, as his family was Irish and this was essentially a holiday home. Another Wimbledon champion who could be said to have a stronger Scottish link was the little known Herbert Lawford, who won the singles title in 1887. Born in Bayswater in 1851, there is no doubt he was English, being brought up in London and educated at Repton, but he began a lifelong attachment to Scotland when he concluded his schooling at Edinburgh Academy in 1868. He then developed his sporting skills while studying at Edinburgh University between 1868 and 1870, in the university cricket team (he also played cricket for Edinburgh Academicals), and practising his court skills at the Rose Street Racket Court. This was several years before lawn tennis was even invented, but he took up the 'new' game with considerable success after returning to London for a career on the Stock Exchange. He first entered Wimbledon in 1878 and is noted as the first player to introduce topspin, beating Ernest Renshaw in five sets in the 1887 final as well as reaching five other singles finals from 1880 to 1888. He was clearly one of the top players of his day. Among other achievements as a sporting all-rounder, he turned out at least once for the famous Wanderers football club. What makes his connection to Scotland much stronger is that he retained a close affinity to the country. He visited regularly and was a shooting tenant of Lauriston Castle near Montrose from the mid 1890s, eventually retiring in 1909 to Aberdeenshire. He bought a house called Drumnagesk at Dess, near Aboyne, where he spent the rest of his life, adding to his sporting interests by joining Aboyne Curling Club. He died there in 1925, aged 73. A little town in Aberdeenshire can stake a claim as the true birthplace of Scottish football, after my discovery that three of the founders of Queen’s Park went to school there.

Brothers Robert and James Smith, and club secretary William Klingner - among the men who met on 9 July 1867 ‘for the purpose of forming a Football Club’ - were all educated at Fordyce Academy before coming to Glasgow in the 1860s. Long since closed but once known as the ‘Eton of the North’, Fordyce Academy enjoyed immense prestige in the Victorian era and there was fierce competition for places. Klingner recorded that first meeting of the Queen’s Park FC in beautiful script (above), but unfortunately for researchers it is not possible to consult his original, which was lost in a fire at Hampden Park early on Boxing Day 1945. We only have this picture of the minute because it was reproduced in Richard Robinson’s History of Queen’s Park, published in 1920, and widely accepted as the definitive version of how the club was formed, and who its founders were. In the course of my research for my book First Elevens, on the first football internationals, I became aware of a few anomalies in Robinson’s text, which had not really been questioned or re-examined. Dublin-born Robinson was described as the club historian, but he was in fact more of a cycling aficionado in his youth and one of the founders of the Scottish Cycling Union. His day job was managing the post office telegraph office in Glasgow, with a sideline as a sports journalist: he launched the Scottish Athletic Journal while football editor of the Glasgow News. Newly retired at the time of the Queen’s Park jubilee, he was in a good position to write the club’s history. Much of his background research was done in 1916 and 1917, but the book had to wait until after the war. There was, however, copious newspaper coverage of the club’s jubilee and two books of press cuttings are held in the Scottish Football Museum. The story begins with a group of young men from the north of Scotland, who in the mid-1860s exercised together every Saturday on a patch of ground in Strathbungo. One of them was James C Grant who, when interviewed in 1916 for the Athletic News, identified the initial group as comprising himself, Robert and James Smith, Donald Edmiston, Lewis Black, and a couple of others. Grant described how they practised traditional Highland sports like hammer throwing, putting the weight, jumping, wrestling and tossing the caber, but when building work made the ground too confined, they decamped to Queen’s Park Recreation Ground in Langside. Again, they found their space being encroached, but this time it was by about forty youths from the local YMCA who were kicking a ball about. The men from the north joined in for their first game of football, and enjoyed it so much that they went into town to buy their own ball. The fact that footballs could then be bought – there was a range at the Royal Polytechnic Warehouse – indicates the game was becoming popular. They added football to their list of activities, and it soon became their primary sport as more and more people joined in; so many, in fact, that in the summer of 1867 they decided to form a proper club. Hence the meeting at 3 Eglinton Terrace, part of Victoria Road in Crosshill, which was attended by about 20 young men, of whom 13 were elected onto a committee. From among them, four office bearers were appointed to lead the club, and research shows that there is an astonishingly close link to these founders, whose origins are in north of Scotland communities just a few miles apart. The exception was Mungo Ritchie, chosen as president, who at the age of 30 was likely considered a senior figure by the players. Born on a farm at Madderty in Perthshire, his father died when he was just six weeks old so it is little surprise that he came to Glasgow to seek his fortune. By 1867 he was established as a draper – a clothes retailer. The north of Scotland connection starts with Lewis Black, first captain, born in 1841 at Cullen on the Moray coast and brought up in Grantown-on-Spey. He would succeed Ritchie as club president the following year and was also a draper. The beautiful script of the minute was written by 19-year-old William Klingner, a merchant’s clerk, who was elected secretary. (Robinson mis-spelled his name as Klinger, and it is only recently that the discrepancy was spotted.) Klingner came from Portsoy, on the Banffshire coast, the son of an émigré from Dresden who was village doctor. And the fourth office bearer, the treasurer, is minuted as ‘Smith senior’. Robinson identified him as Robert Smith, but James was the elder Smith brother by four years. Robert, then aged 19, was actually ‘Smith junior’, among the ordinary committee members. The Smiths were the sons of the Earl of Fife’s head gardener at Innes House in Morayshire, and were prominent figures in early Scottish football despite moving to London at the end of the decade: both were capped for Scotland against England in the first international of 1872. James died relatively young, but Robert headed across the Atlantic and carved out a fine career as a newspaper proprietor and politician in Wyoming, USA. The extraordinary link between them is that it is just five miles from Lewis Black’s birthplace in Cullen to William Klingner’s home in Portsoy, and right in the middle is Fordyce, where the Smith brothers and Klingner were educated. Supported by bursaries and legacies, Fordyce Academy took pupils as boarders as well as day boys, who had to pass highly competitive entrance exams to be accepted. There is no evidence that the boys played football there in the 1850s, but clearly it gave them a taste for outdoor exercise that they continued into adulthood. While Glasgow can claim to be the birthplace of Scottish football, the roots of the founding fathers can be traced to the other end of the country. Fordyce Academy may have closed in 1964, but its legacy remains. |

Archives

July 2024

CategoriesAuthorAll blog posts, unless stated, are written by Andy Mitchell, who is researching Scottish sport on a regular basis. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed