Brothers Robert and James Smith, and club secretary William Klingner - among the men who met on 9 July 1867 ‘for the purpose of forming a Football Club’ - were all educated at Fordyce Academy before coming to Glasgow in the 1860s.

Long since closed but once known as the ‘Eton of the North’, Fordyce Academy enjoyed immense prestige in the Victorian era and there was fierce competition for places.

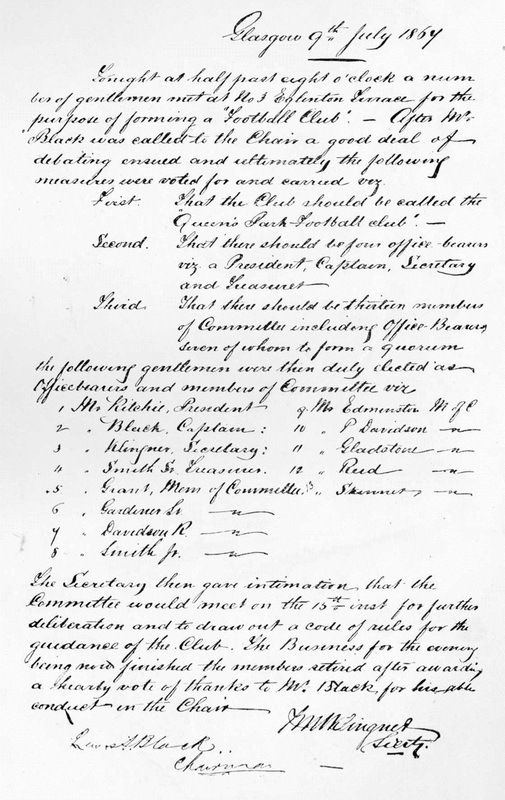

Klingner recorded that first meeting of the Queen’s Park FC in beautiful script (above), but unfortunately for researchers it is not possible to consult his original, which was lost in a fire at Hampden Park early on Boxing Day 1945. We only have this picture of the minute because it was reproduced in Richard Robinson’s History of Queen’s Park, published in 1920, and widely accepted as the definitive version of how the club was formed, and who its founders were.

In the course of my research for my book First Elevens, on the first football internationals, I became aware of a few anomalies in Robinson’s text, which had not really been questioned or re-examined. Dublin-born Robinson was described as the club historian, but he was in fact more of a cycling aficionado in his youth and one of the founders of the Scottish Cycling Union. His day job was managing the post office telegraph office in Glasgow, with a sideline as a sports journalist: he launched the Scottish Athletic Journal while football editor of the Glasgow News. Newly retired at the time of the Queen’s Park jubilee, he was in a good position to write the club’s history.

Much of his background research was done in 1916 and 1917, but the book had to wait until after the war. There was, however, copious newspaper coverage of the club’s jubilee and two books of press cuttings are held in the Scottish Football Museum.

The story begins with a group of young men from the north of Scotland, who in the mid-1860s exercised together every Saturday on a patch of ground in Strathbungo. One of them was James C Grant who, when interviewed in 1916 for the Athletic News, identified the initial group as comprising himself, Robert and James Smith, Donald Edmiston, Lewis Black, and a couple of others. Grant described how they practised traditional Highland sports like hammer throwing, putting the weight, jumping, wrestling and tossing the caber, but when building work made the ground too confined, they decamped to Queen’s Park Recreation Ground in Langside.

Again, they found their space being encroached, but this time it was by about forty youths from the local YMCA who were kicking a ball about. The men from the north joined in for their first game of football, and enjoyed it so much that they went into town to buy their own ball. The fact that footballs could then be bought – there was a range at the Royal Polytechnic Warehouse – indicates the game was becoming popular.

They added football to their list of activities, and it soon became their primary sport as more and more people joined in; so many, in fact, that in the summer of 1867 they decided to form a proper club. Hence the meeting at 3 Eglinton Terrace, part of Victoria Road in Crosshill, which was attended by about 20 young men, of whom 13 were elected onto a committee.

From among them, four office bearers were appointed to lead the club, and research shows that there is an astonishingly close link to these founders, whose origins are in north of Scotland communities just a few miles apart.

The exception was Mungo Ritchie, chosen as president, who at the age of 30 was likely considered a senior figure by the players. Born on a farm at Madderty in Perthshire, his father died when he was just six weeks old so it is little surprise that he came to Glasgow to seek his fortune. By 1867 he was established as a draper – a clothes retailer.

The north of Scotland connection starts with Lewis Black, first captain, born in 1841 at Cullen on the Moray coast and brought up in Grantown-on-Spey. He would succeed Ritchie as club president the following year and was also a draper.

The beautiful script of the minute was written by 19-year-old William Klingner, a merchant’s clerk, who was elected secretary. (Robinson mis-spelled his name as Klinger, and it is only recently that the discrepancy was spotted.) Klingner came from Portsoy, on the Banffshire coast, the son of an émigré from Dresden who was village doctor.

And the fourth office bearer, the treasurer, is minuted as ‘Smith senior’. Robinson identified him as Robert Smith, but James was the elder Smith brother by four years. Robert, then aged 19, was actually ‘Smith junior’, among the ordinary committee members.

The Smiths were the sons of the Earl of Fife’s head gardener at Innes House in Morayshire, and were prominent figures in early Scottish football despite moving to London at the end of the decade: both were capped for Scotland against England in the first international of 1872. James died relatively young, but Robert headed across the Atlantic and carved out a fine career as a newspaper proprietor and politician in Wyoming, USA.

The extraordinary link between them is that it is just five miles from Lewis Black’s birthplace in Cullen to William Klingner’s home in Portsoy, and right in the middle is Fordyce, where the Smith brothers and Klingner were educated.

Supported by bursaries and legacies, Fordyce Academy took pupils as boarders as well as day boys, who had to pass highly competitive entrance exams to be accepted. There is no evidence that the boys played football there in the 1850s, but clearly it gave them a taste for outdoor exercise that they continued into adulthood.

While Glasgow can claim to be the birthplace of Scottish football, the roots of the founding fathers can be traced to the other end of the country. Fordyce Academy may have closed in 1964, but its legacy remains.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed