This is the story of an extraordinary week in 1997 when events unrelated to football conspired to make the Scottish Football Association and its boss vilified throughout the UK.

I had recently been appointed press officer to the Scottish FA, an opportunity to combine two decades of experience in the media with my love of football. Working at the SFA, then based in a grand Victorian townhouse in Park Gardens, was like stepping back in time. Its antiquated methods and hierarchy took some getting used to, not least the principle that every decision, every comment, every announcement, had to be personally approved by the chief executive, the supreme autocrat, Jim Farry.

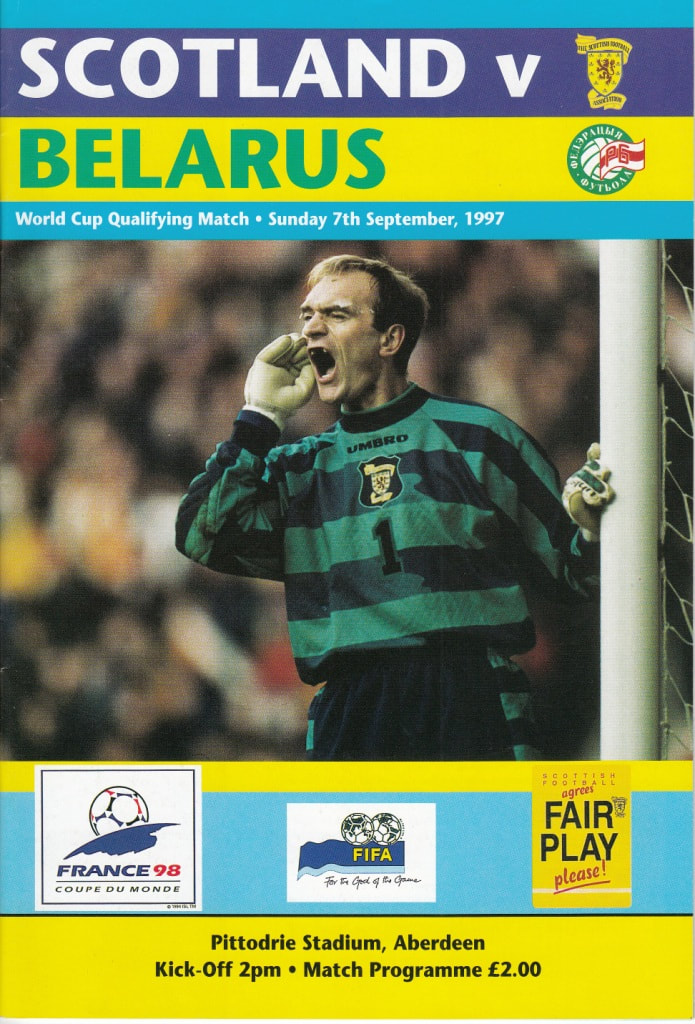

Despite all that, working in football was a dream job for me. As I looked forward eagerly to my first match as an SFA employee, a World Cup qualifier between Scotland and Belarus, nothing could have prepared me for what unfolded.

Like most of Britain, I found out on Sunday morning that the Princess had been killed. As I came downstairs, instead of the usual noise of kids' cartoons on the telly, there was funereal music and hushed voices. The national outpouring of grief for Diana had begun.

In a previous life, ten years earlier, I had once covered a visit by Diana and Charles to the Middle East. I was editing a magazine in Oman at the time and joined the press pack as they followed the royal couple on their round of visits and even to a polo match where Charles fell off his horse. The fun of those few days contrasted acutely with what was about to hit me.

Monday 1 September

I was still living in Perth, house-hunting in Glasgow, so my morning commute was a long one but the news on the car radio gave no cause for concern. The Palace announced that morning that Diana’s funeral would take place on the Saturday, the day Scotland was scheduled to play Belarus in Aberdeen, but a morning funeral and an afternoon match did not seem, to us, to conflict. However, speculation soon started about the viability of the match going ahead on a day of mourning, so the SFA sounded out as many relevant bodies as possible, starting with the competition organisers.

FIFA's view was that it is not uncommon to be faced with such circumstances, she was not a head of state in any case, so the match should go ahead with all normal marks of respect such as a minute’s silence and flags at half mast.

Our opponents, Belarus, were already aware from media reports that the match may have to be moved and in fact they contacted us first. Language proved a difficulty, and discussion was done through German-speaking staff members on both sides. We said we would keep them informed of developments.

Next up was the Sports Policy Unit of the Scottish Office, to ascertain the government’s view. Remember, there was no Scottish Government at the time, although the devolution referendum was scheduled for later that month. The response came back: 'It is not for the government to intervene or seek to make any arrangements in such matters.' They made it clear that it was entirely for the SFA to make a decision.

And finally, the Lord Chamberlain's Office at Buckingham Palace, for protocol guidance. This proved a stumbling block, as you can imagine the switchboard at the Palace was constantly engaged. Finally, a fax went through that evening, expressing condolences and requesting guidance.

I was not involved in these discussions, as at that stage there was no particular media pressure, no cause for concern, and in fact I went to Livingston for a planning meeting ahead of them hosting an Under 21 match the following month. That evening, I drove home at the usual time, and all the signs pointed to the Belarus match going ahead as scheduled on the Saturday afternoon. It was calm. Nobody foresaw the hysteria that would mount so forcefully and quickly.

Tuesday 2 September

In the office, as we carried on planning as normal. I remember the page proofs for the match programme came in for checking – in those pre-digital days they were cromalin sheets. Then, what appeared to be the final piece in the jigsaw fell into place just before one o'clock. A senior official in the Lord Chamberlain’s Office called Farry and gave his view that, provided the match did not conflict directly with the funeral service (which it didn't), there was no protocol problem with the match taking place. He added, 'life goes on'. In our closeted world, that was the green light we were looking for.

A fax duly went to the Belarus FA, confirming that the match would go ahead as planned, and this was then announced via the Press Association at about 2pm.

Matter resolved? Not a bit of it. All hell broke loose. It was the cue for a nationwide outbreak of moral outrage directed at the SFA, and more precisely the person of Jim Farry, for daring to sully the day of mourning. Having tried to play by the rules, a decision taken for logical and administratively sound reasons was portrayed as a treasonable offence. The faxes and phone calls poured in. Suddenly and unexpectedly, the SFA was under siege.

It may just have ridden that storm, being well used to ignoring public opinion, but there was another unforeseen factor: the referendum for the Scottish Parliament was just ten days away.

The SFA lost control of events shortly after 9pm when Donald Findlay QC, the vice chairman of Rangers, appeared on the BBC network news to denounce the SFA, and Farry in particular. Findlay may have been asked to give his opinion on a football matter, but he was not just a football man, he was also a leader of the Think Twice movement which opposed the setting up of the parliament. Even though a halt had been called to referendum campaigning that week because of the tragedy, he seized the opportunity to point out, 'this is what happens when Scots try to run their own affairs'.

He knew the impact his comments would have and he boxed the pro-parliament campaigners into a corner. Late that night Donald Dewar, the Secretary of State for Scotland, phoned Farry to express his 'great concern' about the match going ahead as planned. If that was not enough, he upped the ante by enrolling prime minister Tony Blair's support for a cancellation, and this was quickly echoed by William Hague, the Tory leader. All this was, of course, in complete contradiction to the advice given the day before.

Wednesday 3 September

Some time during the night, someone daubed the front door at Park Gardens with paint: 'Please call the game off'. Mysteriously, it was done just in time for a photo of the message to be published in the Daily Record. The caretaker Mike Kinrade, who lived in a flat above the office, set to work with wire brush and turps.

Farry, meanwhile, did his case no favours by joking about the matter. He responded flippantly to Donald Dewar’s call, saying 'Colin Hendry’s out of the game and big Donald might be a valuable addition to the back four.' More sensibly, he pointed out 'We have taken heed of the various viewpoints, but let’s be reasonable about this – life does and must go on. We know stores will open at 2pm on Saturday. We agree with that. It is a mark of sensitivity. We will open at 3pm.'

His voice of reason, and his argument that there were 'insurmountable difficulties' made little headway in the face of intense political and public pressure. Labour MP Jimmy Hood thundered 'The decision of the Scottish FA has brought shame on Scotland.' And it was not just politicians: Denis Law said 'I would ask not be to be selected if the game was going ahead. The whole nation will be joined in mourning and showing their respect. You just feel the SFA have got to have a rethink.'

Yet there appeared little room for manoeuvre. Belarus were prepared to move the kick-off back a few hours but that idea was blown out of the water when the Rangers players in the squad - Ally McCoist, Gordon Durie and Andy Goram - told Craig Brown they would not play on the Saturday at any time.

The Scottish Office had suggested Friday, but the Belarus FA could not play on Friday evening as several of their players were involved in matches in Russia on the preceding Wednesday. And, as they had another World Cup qualifier to play against Austria on the following Wednesday, they said initially that Sunday was not a possibility either.

There were other significant practical considerations: the host club, Grampian police, the referees, the catering and stewarding, and not least the 20,000 supporters who had bought tickets and made travel arrangements.

Meanwhile, our main rivals in the World Cup qualifying group, Austria and Sweden, pointed out that Scotland would gain an unfair advantage by postponing the match and playing it at a later date. In any case, there were no realistic dates available.

Throughout Wednesday, the SFA international committee made efforts to resolve the crisis, meeting at Park Gardens behind closed doors. It proved such an intractable problem that SFA president Jack McGinn revealed that they had even considered withdrawing Scotland from the World Cup altogether.

Meanwhile, I was oblivious to these deliberations. I had escaped Glasgow to travel up to Aberdeen to be with the Scotland squad, where a press conference was scheduled that afternoon at the team hotel, the Marcliffe. It was ostensibly for Craig Brown to preview the match, but there was only one topic on the agenda. I sat next to him at the top table, still in the dark about the progress of the negotiations, and totally unprepared to face questions. Not surprisingly, I was savaged by the impatient media who wanted answers. The SFA had yet to learn how to explain its decision-making process in a crisis.

I had also yet to learn that these new-fangled mobile phones didn’t have limitless power. With incessant calls from journalists seeking updates, my battery expired and, rather embarrassingly, I had to spend much of the evening standing at the hotel reception so I could use their phone to keep in contact with head office.

Back in Glasgow, the breakthrough came when the Belarus FA agreed to accept Sunday, but only after the SFA undertook to cover the additional £25,000 costs of their charter aircraft and hotel accommodation for Saturday night. Finding sufficient bed space in Aberdeen during a major oil conference was just another of many local difficulties!

Even reaching a formal agreement with the Belarus FA on this basis was problematic as their president, Evgeni Shuntov, did not speak English. His wife did, but she would not be home until 7pm to act as translator. Then further difficulties arose with permission being needed from the Belarus Minister for Aviation for the charter flight to be delayed, and this was only achieved after pressure from the Belarus Ambassador to the UK.

The other pieces gradually slotted together. Donald Dewar agreed that Sunday afternoon would be acceptable. Grampian Police and Aberdeen FC consented. Austria and Sweden concurred, albeit grudgingly. FIFA proved more difficult, as all the relevant people were in Cairo at a conference and could not be contacted, but the message did eventually get through. The referee team from the Netherlands and the Czech delegate were rescheduled.

Finally, just after 9pm, I took a call from Farry, who dictated a statement to me and five minutes later, having called the journalists and TV crews into the hotel lobby, I read out his words. At the same time, he did so on the steps of Park Gardens: 'The SFA, in an attempt to find a solution, has received a tremendous level of co-operation from Belarus. They have been considerate and helpful. We are proposing to FIFA by fax that the match be played on Sunday, probably at 2pm. If that necessary approval is forthcoming then we have a solution. In satisfying the majority it will be necessary to inconvenience the spectators. We hope for their understanding and look forward to welcoming them on Sunday.'

Craig Brown answered the follow-up questions in his usual diplomatic manner: 'The SFA has told me the game is now planned to go ahead on Sunday and I will have a team ready. In the circumstances I am sure it was the correct decision to take.'

Shortly afterwards I headed for home, a three hour drive down the road to Perth. It has been a long day.

Back in Glasgow the following morning, the key issue may have been resolved, but the recriminations continued. 'Go now!' was the Daily Record’s headline advice to Jim Farry, while the Scottish Sun screamed 'Off – and so should you be'.

The nation was angry and wanted to let us know. This was long before social media, and even email was not yet widespread, so people phoned, wrote or even came to the front desk.

The limitations of the SFA's antiquated switchboard became abundantly clear: it could only handle six calls at a time, in or out. Only a few senior staff (and certainly not the press office) had direct lines. The calls flooded in, and to keep the lines operating they were spread throughout the office to anyone available. Many of them came my way, and there was little I could do except acknowledge the callers' bitterness, much of it personal against Farry. I remember one call particularly, where the man on the phone backed up his complaint by asserting 'Well he’s no oil painting, is he?' as if to say Diana’s beauty had been defiled by him.

There was a fax machine which spewed out letters of protest all day long, and even the old Telex sputtered into action, the only time I ever saw it operating. The post arrived with the first wave of sackloads of letters.

Not all the messages were critical, in fact about a third of them were supportive. It would have been easy to bin them but, in line with Farry’s policy, every one of them got an answer, which of course kept the clerical staff busy for weeks. They are still filed away in boxes somewhere, I believe.

Friday 5 September

Things were calming down by Friday although Farry, reflecting to the press on what had happened, was clearly aggrieved: 'It seems obvious to me there has been an awful lot of cant and hypocrisy about this matter. Worse, there has been deliberate massaging of reports and clever juxtapositions of truths which has raised media spin to an art form.' He was unrepentant: 'I don’t feel any inclination to apologise. I may feel an inclination to review it with the benefit of hindsight but I don’t think an apology would be an appropriate response at this time.'

The staff rallied round and we returned to planning the match itself, with Farry making it clear to everyone round the table that this was one game where every aspect of our organisation had to be perfect. The welcome message in the programme was rewritten, and the date was changed on the embroidered match pennant.

Some football even got played that evening and I went to see Scotland Under 21s lose 3-0 to their Belarussian counterparts at McDiarmid Park.

Saturday 6 September

After watching the funeral on TV I went into Perth city centre. It was busy: the shops opened at 2pm, and they were not short of customers. There were many people by that time fed up with the whole affair and wanting to get on with their lives.

Up in Aberdeen, there was an unreported element of farce. Being a FIFA match, the players had to show their passports to the referee and one player had forgotten his. David Hopkin's wife posted it to the team hotel but by Saturday morning it had not arrived and our security chief, Willie McDougall, had to persuade staff at the local Royal Mail sorting office to wade through the mountain of mail to find the missing package.

Shortly before 2pm, a lone piper stood in the middle of Pittodrie and played a lament, Flowers of the Forest. That was Farry’s idea. The capacity crowd stood in silence, but as soon as the music stopped a roar went up and normal service was resumed. Scotland won 4-1 and Hopkin, armed with his passport, scored twice. Qualification was secured a month later and the following summer we faced Brazil in the opening match of the World Cup Finals.

The whole affair seemed over in a flash. In my opinion, it was whipped up and sustained by the media, who feared a public backlash against their own hounding of Diana, which had led indirectly to her death. They needed a scapegoat for the killing of the nation's favourite princess, and latched onto the first available target to deflect that criticism.

Jim Farry not only fitted the bill, he played into their hands as the pantomime villain. He once told me that media relations was his forte, but in that he was deluded. Regardless of the challenging circumstances, he could have handled it much better, displaying not just a lack of sensitivity but an inability to read the public mood until it was too late. He was on borrowed time and two years later he was out of a job.

For me, it was my baptism of fire, a major learning curve. However, I soon realised that crises and public scorn were common currency at the Scottish FA. Over the next ten years I had plenty of practice dealing with that side of things.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed