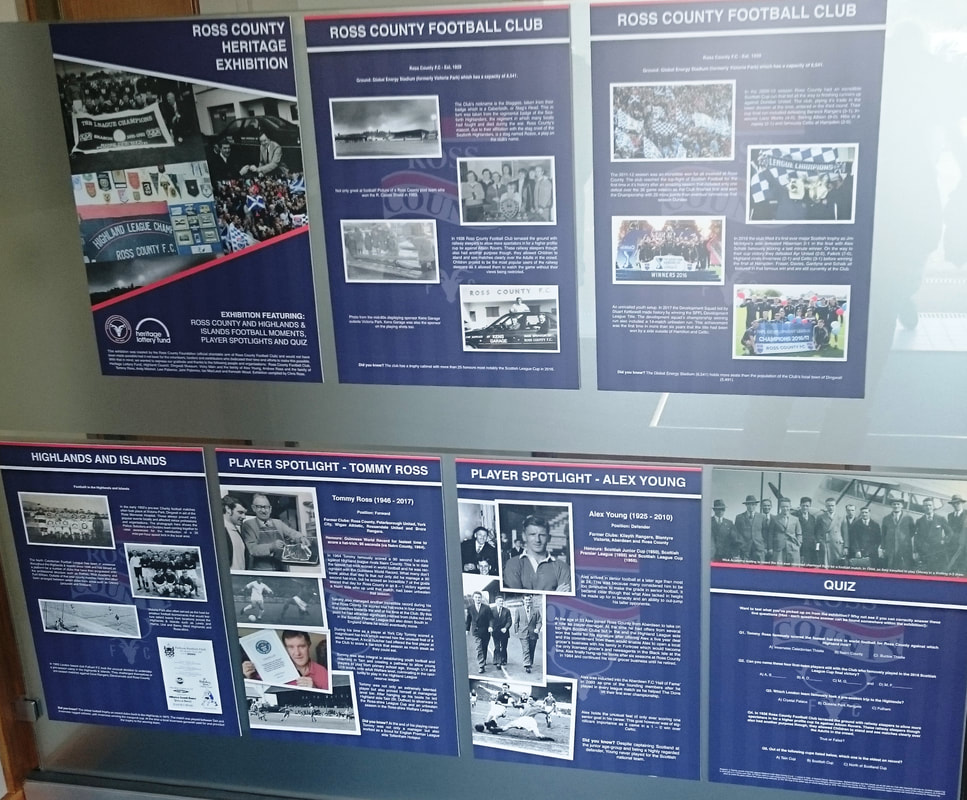

The display panels are portable so they can be taken to schools, and should be a great tool for generating a wider interest and appreciation of how Ross County got to where they are now. Formed as late as 1929 as the northernmost club in the Highland League, their rise in recent years to the top level of Scottish football is nothing short of extraordinary.

Just thirty years ago, in 1987, the club finished bottom of the Highland League in the midst of a cash crisis, yet it bounced back to win two titles in the early 90s and was then elected to the Scottish League in 1994. Steady progress through the divisions saw them reach the Premier Division in 2012, and then win their first national trophy, the Scottish League Cup, in 2016.

There is a risk that the younger generation might take this level of success for granted, so this kind of exhibition is a great way of reminding (or introducing) people of the area's footballing roots.

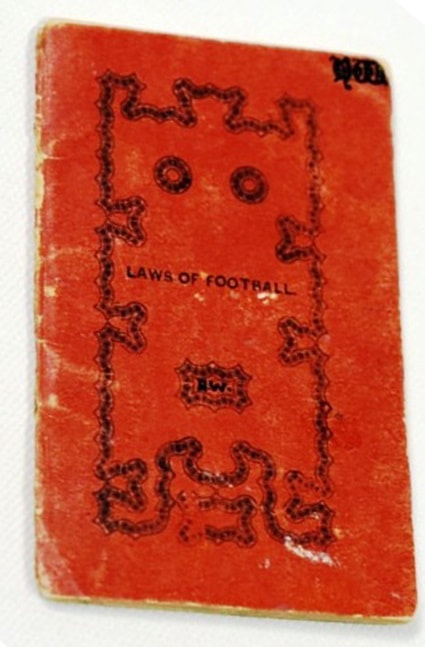

There is also a celebration of the wider football heritage of the Highlands, and one story that particularly intrigues me is the little known fact that Scotland's first football cup was contested in Tain, four years before our oldest national trophy, the Scottish Cup.

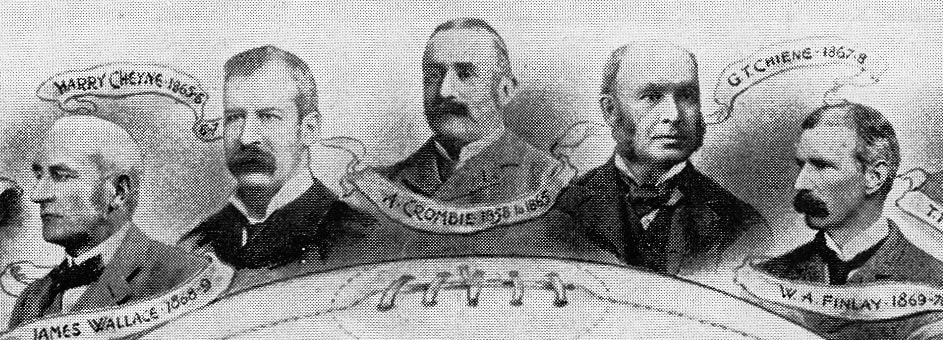

In June 1870, a local businessman, Thomas Beales Snowie, paid £5 for a silver cup to be awarded to the winners of a match between Tain Ragged School and Inverness Reformatory School. There was a joint team photo before the match, which was won by Inverness. They were presented with the cup while the Tain boys were presented with a football to practise with. However, although there were proposals for a rematch the following year it was a one-off.

This historic trophy's whereabouts are now unknown, and it would be a fantastic find it it could be located. Hopefully this exhibition will inspire a local historian to find out what happened to it.

With thanks to Chris Ross of the Ross County Foundation for the invitation to the launch and the match.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed