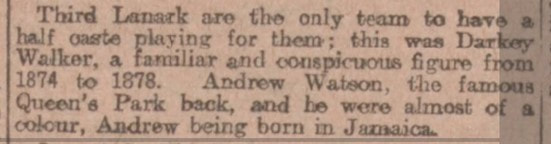

That honour belongs to Robert Walker of Third Lanark and Parkgrove, who played in the 1876 Scottish Cup final and was a trialist for Scotland.

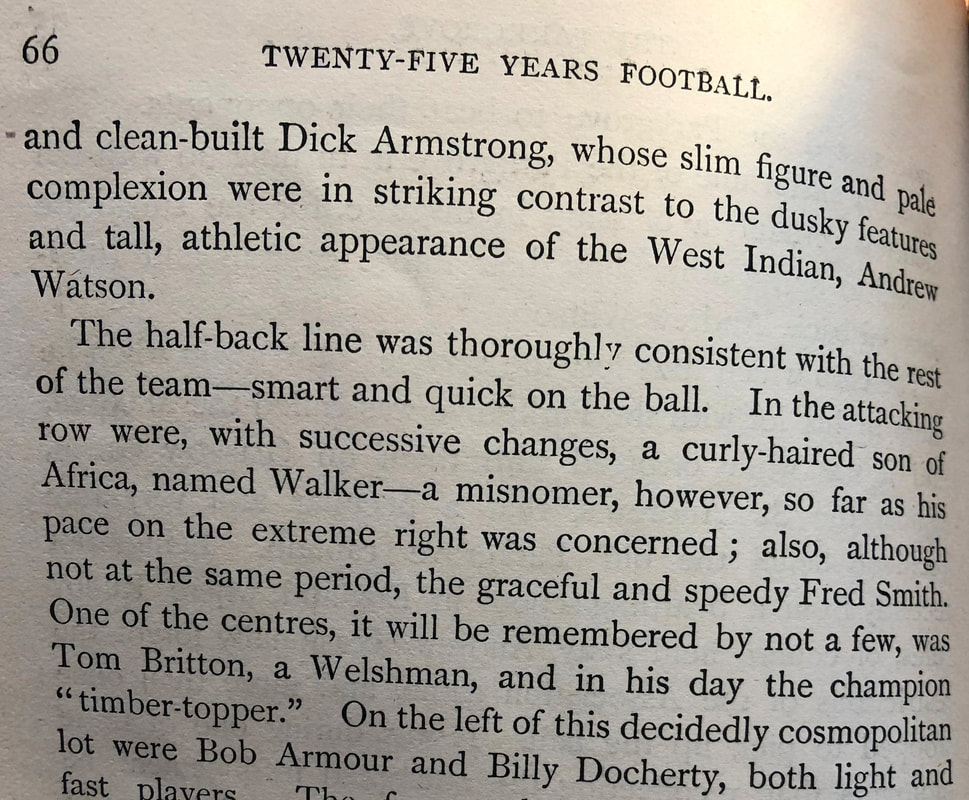

Once described as a 'curly-haired son of Africa', Walker was largely forgotten until his existence was highlighted in 2015 by Richard McBrearty of the Scottish Football Museum. However, with a common surname and a fleeting connection to Glasgow, his identity remained a mystery.

I can now tell his story and give him his due place in football history.

Although he played for Queen's Park Juniors he never got into the first team and in the summer of 1875 he moved to near neighbours Third Lanark. Aged just 18, his pace on the right wing was a great asset to the team in 1875-76, and he played his part as Thirds reached the Scottish Cup final, scoring against Western in the quarter final and against Dumbarton in a semi-final replay. They came desperately close to lifting the trophy in March 1876, taking the lead in the final only for Queen's Park to equalise, and the Hampden giants then won the replay 2-0.

Walker's precocious talent was recognised as he was selected twice that season for Scotland international trial matches, for the Blues on 19 February and the Improbables on 1 March, without making the final cut. Perhaps if he had given a better showing he might have been our first internationalist.

Like many footballers, in summer he took part in sports meetings, and in September 1876 at the Queen's Park Sports he came across Andrew Watson, perhaps for the first time. Walker placed second in the half mile race for members, while Watson competed in the high jump.

Throughout the 1876-77 season Walker continued to feature on the right wing for Third Lanark, occasionally scoring goals, and again was asked to play in a Scotland trial in February, representing Mr McGeoch's team. However, that was as close as he came to an international cap.

I would love to have witnessed the fifth round tie between Parkgrove and Partick, which was full of players whose names still resonate today. The Partick team included Fergie Suter and Jimmy Love, whose move to Darwen in the autumn of 1878 would be the catalyst for professionalism in football.

Parkgrove, meanwhile, had Walker and Watson who were black, their goalkeeper was Tommy Marten of Chinese extraction, with Wales internationalist Thomas Britten thrown in for good measure. It was a more cosmopolitan and ethnically diverse team than any other Scottish club in the next hundred years.

The teams actually had to meet twice, a 1-1 draw followed by a 2-1 victory for Parkgrove, who were no doubt helped that between the two Scottish Cup ties Partick made a New Year trip to Lancashire for friendlies against Darwen and Blackburn Rovers.

In 1878, Walker's football career came to an end when he left Scotland for Liverpool to pursue a career in marine engineering.

This is one of several striking similarities between his life and that of Andrew Watson: they were the same age, both sons of a relationship between a white Scot working abroad and a local woman; they were both sent back to the UK for their education and barely knew their fathers; both took up football when they arrived in Glasgow as young men; and both retired to London when their maritime career was over.

His father was Alexander Walker, a Scottish merchant who spent most of his working life in Sierra Leone where he was a prominent figure, at one point president of the Chamber of Commerce. Alexander came home on leave to Dumfries in 1852 to get married to Jane Haig, but it appears it was a marriage of convenience as he soon went back to Sierra Leone without his new wife, and the following year the first of three sons was born to his black partner, Judith Jarrett. Their youngest son was baptised in Freetown on 23 January 1857 as Robert Gustave Walker.

Robert spent very little time in Sierra Leone and he and his elder brothers Walter and Allan were brought up by their great aunt Agnes at Preston Mill, south of Dumfries, where he was known locally as 'Black Bob' and probably went to Kirkbean parish school (whose most famous former pupil was John Paul Jones, father of the American Navy). The boys may have finished their schooling in Dumfries.

Their father continued to be based mainly in Sierra Leone, although latterly he worked as a shipping agent in London until his death in 1870. He left a comfortable legacy to his four surviving children (Allan had died young while he had a son and daughter from yet another relationship), albeit they had to wait until they were 24 years old to access it.

Walter became a farmer near Dumfries and Robert (Bob) chose his own path. He came to Glasgow in 1874 but whether to study or to work is currently unknown. There is a family story that he may have studied medicine, but he is not in the matriculation lists of Glasgow University and student records of other colleges have not survived.

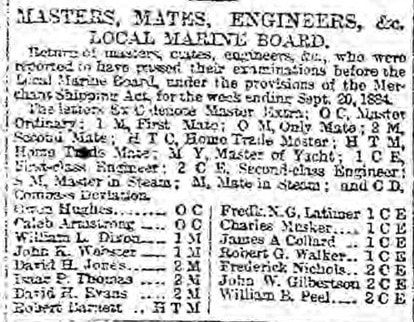

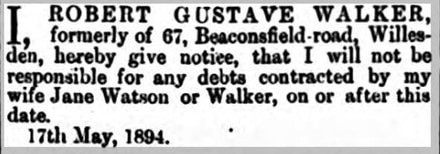

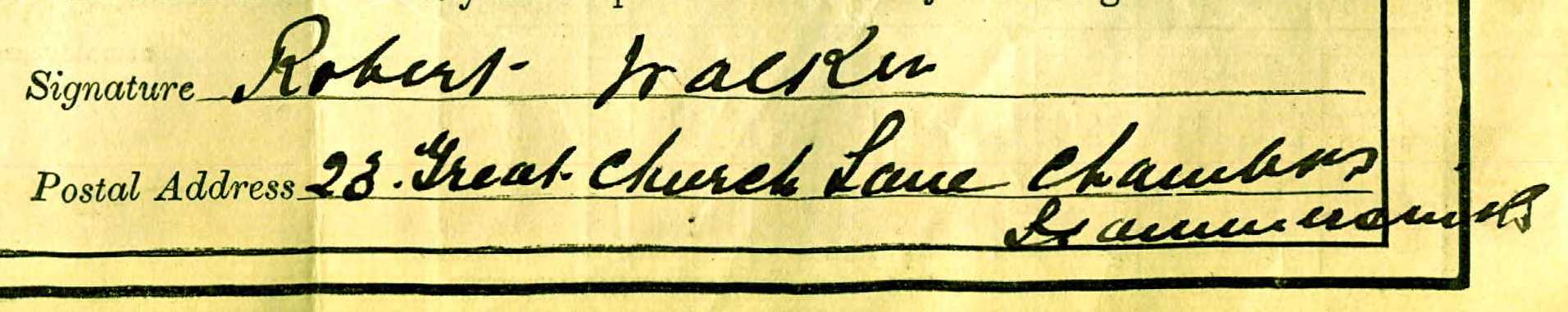

After four years in Glasgow he went to Liverpool to embark on a maritime career. He married there in 1881 to Jane Watson, daughter of a Scottish engineer, and over the next few years on Merseyside he served on a variety of merchant navy ships and passed his exams as a Second Engineer and then First Engineer (exactly the same Local Marine Board certificates that Andrew Watson would take later in the decade).

It was the springboard to a successful career as he rose to become Chief Engineer for the Elder Dempster line, which plied routes between Britain and Africa and no doubt gave him the opportunity to visit his birthplace in Sierra Leone.

When his sea-going career was over he lived with Alice in London and died in Hammersmith in 1936, aged 79. Sadly, there is no gravestone to mark his last resting place in Hammersmith Cemetery.

What of his legacy? Walker succeeded in football (and in his career) despite being black, and it is remarkable that Scottish sport in general was so ethnically diverse in the 1870s, a phenomenon which does not appear to have been replicated elsewhere in the UK.

It was not just the footballers Watson, Walker and Marten: looking at the bigger picture, I have previously written about rugby player James Robertson and athlete William Forman, both black, while Scotland rugby internationalist Alfie Clunies-Ross was of Malayan descent. And those are just the ones we know about – there may well be more, waiting to be discovered.

All of these black or Asian sportsmen appear to have been judged on their skill rather than their race, and were able to compete without any obvious discrimination or adverse comment in the press. This is in stark contrast to, say, attitudes towards the first women footballers, or the sectarianism and racism that became so pervasive in the twentieth century.

Robert Walker is important as Scottish football's first black pioneer, and now that his story has finally come to light, his place in history can be assured.

Born January 1857 (baptised 23 January) in Freetown, Sierra Leone.

Died 11 March 1936 in Hammersmith, London.

Football career:

Queen's Park 1874-75 (did not play for first team).

Third Lanark 1875-76 (Scottish Cup finalist) and 1876-77.

Parkgrove 1877-78.

Scotland trial matches (3): 19 February 1876, 1 March 1876, 17 February 1877.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed