In the autumn of 1878, two Scottish footballers moved to Lancashire. James Love and Fergus Suter left Partick to join Darwen, where they became, almost certainly, the first professional players.

That much is recorded in histories of the game. But what is not explained is why those particular men chose that particular moment to move between those particular clubs. In this paper I will demonstrate that it was not a random event, outlining the specific circumstances that led to Love and Suter exchanging a Glasgow suburb for an East Lancashire mill town, 200 miles away. And I will also, for the first time, reveal the identity of James Love.

To begin with, however, some context. It is a challenge for historians to say definitively who the first professional football player was, as payments were made illicitly in various round-about ways, and nobody ever confessed. Some claim it was the Glaswegian JJ Lang, who went to Sheffield Wednesday in 1876, but he seems to have benefitted from a benevolent employer giving him time off, rather than taking any direct payment from the football club.

To complicate matters, in fact many players moved across the border, in both directions, usually because of their work. To take just one example, the Smith brothers, Robert and James, had both been founders of Queen’s Park in 1867, and moved to London for work a couple of years later; both played for Scotland in the first international match of 1872, just a week after turning out for South Norwood in the FA Cup. But there is no question that they were amateurs.

Cross-border connections such as these were crucial for the spread of association football. Queen's Park was first club from Scotland to undertake matches against English sides but it was not until New Year's Day 1876 that a second Scottish club fulfilled a match in England. That team was Partick, who travelled to face Darwen.

The explanation for the link lies with a footballer who crossed the border, going north. He was called William Kirkham (1854-1909), born and brought up in Darwen but who had gone to Partick for work - he was a colour mixer in the textile industry, a skilled job. While in Scotland he was a founding member of Partick football club in 1875, and when he returned south a couple of years later, he resumed playing for Darwen. Kirkham was the catalyst for inaugurating the relationship between Partick and Darwen, and it quickly developed, on and off the field. But there is much more to this than the personal link with William Kirkham, which was only the first piece in the jigsaw.

That first match in 1876 launched a series of matches between the two clubs, which gave rise to further contacts in Lancashire as Partick also played Blackburn Rovers three times in 1878 and 1879, and later faced Turton and Bolton:

1 January 1876 Darwen 0 Partick 7

10 November 1877 Partick 5 Darwen 0

1 January 1878 Darwen 3 Partick 2

2 January 1878 Blackburn Rovers 2 Partick 1

9 November 1878 Partick 2 Blackburn Rovers 0

1 January 1879 Darwen 0 Partick 7

2 January 1879 Blackburn Rovers 2 Partick 4

1 January 1880 Turton 3 Partick 5

2 January 1880 Bolton & District 3 Partick 3

2 October 1880 Darwen 4 Partick 1

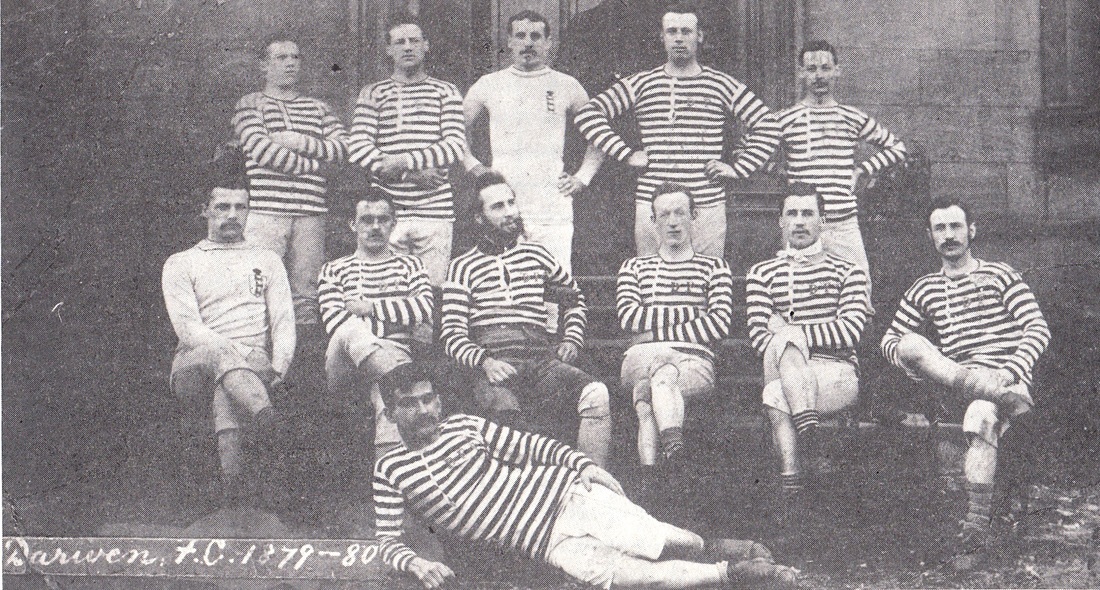

Through these games, Partick became extraordinarily influential by supplying players for Lancashire football. They effectively acted as a 'shop window' for talented Scots who would become the earliest paid players in England. Have a closer look at the teams from 1 January 1878:

Darwen: J Booth, J Duxbury, A McWetherill, R Crookes, T Hindle, T Marshall, R Kirkham, J Knowles, J Lewis, T Bury, J Hayes.

Partick: E Suter, F Suter, A Stewart; R Love, A McGaw; J Love, J Keay, WH Kirkham, WG Struthers, W McLachlan and JN Boag.

Of the Partick players I have highlighted, five played for Darwen before the end of the decade – the Suter brothers Edward and Fergus, Jimmy Love, William Kirkham and William McLachlan – and for good measure William Struthers went to Bolton Wanderers, while John Boag later married a Bolton girl. In subsequent years several other Partick players also joined clubs in Lancashire.

And among the Darwen players was Tommy Marshall, a future England football international who won numerous cash prizes as a champion sprinter on the professional athletics circuit, and Ralph Crookes, employed as the club's cricket professional.

Clearly, Darwen was open-minded towards the morality of rewarding sporting talent with payment. And crucially, the club also acquired the means: as early as March 1878 they played local rivals Turton and drew a gate of £18, which prompted the local press to remark that the Darwen committee 'were almost at a loss as to what to do with such an enormous sum'. The answer soon became apparent, especially as that £18 figure was soon dwarfed by gate receipts which reached well into three figures within the next couple of years.

So, we come to the 1878/79 season, which was memorable for a number of reasons. Jimmy Love was first to arrive and a few weeks later Fergie Suter made his Darwen debut at full back. Their presence had a revolutionary effect as they were schooled in passing and combination play, which not only raised standards, it took Darwen to the FA Cup quarter final, the first northern team to reach that stage.

They faced Old Etonians over three matches, all played in London, and the story is well known. In the first game, Old Etonians led 5-1 at half-time, but a whirlwind response levelled it at 5-5 including two goals from Love. The Etonians, fearing defeat if the match carried on, refused to play extra time. In the replay Darwen drew 2-2, and it was only at the third attempt that Old Etonians prevailed. A fortnight later they won the FA Cup itself.

That cup run brought nationwide publicity for Darwen, especially as there was an element of mystique about Scots 'professors'. It was good box office, Darwen wanted more, and other clubs soon latched on.

So, how did it come about? At the time there was no mention in the press whether Love and Suter were paid to pay football, but Suter was candid enough to admit it later in life, when interviewed about his career:

'On what plan were you paid in those days?' he was asked, responding: 'Well, we had no settled wage, but it was understood that we interviewed the treasurer as occasion arose. Possibly we should go three weeks without anything, and then ask for £10. We never had any difficulty.' [Lancashire Daily Post, 13 December 1902]

This is as near as you can get to proof that Love and Suter were paid directly by the football club. And if the occasional tenner wasn't enough, at a time when a working wage was less than two pounds a week, Darwen played a benefit match for Love and Suter in April 1879.

But the relationship was short-lived. While Suter spent the rest of his life in Lancashire, Love played his last game for Darwen in October 1879, just a year after his debut. He then turned out once for Blackburn Rovers, made an appearance for Haslingden in January 1880, and promptly disappeared.

So what happened to him? Who was James Love, a key figure in football history, probably the first man ever to receive payment for playing the game? He has never been identified until now. There was no mention of his background or his circumstances in the papers, while Keith Dewhurst, who recently wrote a book [Underdogs, 2012] about the Darwen team, wrongly identified him as a shipyard worker – but that man remained in Partick all his life and died in an accident at work in 1894.

Tracking him down was not easy. Years later, there were cryptic clues in press articles that he had been killed in the bombardment of Alexandria in 1882 – but Love was not listed among the few British casualties. Then, searching more widely, I found that a Corporal Love of the Royal Marines had died of illness in Egypt, a couple of months after the bombardment of Alexandria. This led me to a family notice in the Glasgow Herald:

At Ismailia, of enteric fever, on 27 September aged 24, Corporal James Love, Royal Marine Light Infantry, eldest son of James Love, late of Greenock. [Glasgow Herald, 9 October 1882]

Now, Greenock is a fair distance from Partick, but this seemed as good a lead as any. After a lot of painstaking research, piecing together his life story, I found sufficient evidence not only to confirm that this was indeed him, but also to shed light on his reasons for going to Darwen.

James Love was born in Gushetfaulds Cottage in Glasgow in 1858, his father the manager of a coal depot attached to South Side railway station and goods yard. When he was nine, his father – also James Love – gave up this job to set up a contracting business, which included coal supply, street cleaning and disposal of horse manure. The family moved to Greenock then on to Glasgow and, to cut a long story short, in the summer of 1877 the business failed and the father was declared bankrupt.

Meanwhile, James junior also set himself up as a street-cleaning contractor in Partick but before long he too got into financial difficulties and a horse dealer called in an unpaid debt.

In October 1878, his two horses and his equipment, including a street-sweeping machine, were sold off at a public warrant sale. A couple of weeks later he was summoned to the Glasgow bankruptcy court but when he failed to show up, the court postponed the case for a month. On 21 November 1878, he again failed to appear, so Sheriff Walter Spens issued a warrant for his arrest. It was never served: James Love had run away from his debts. He had gone to Darwen.

That escape route was open to him thanks to his skills as a footballer and his friendship with William Kirkham. Also, Love had already visited Lancashire with Partick at New Year 1878. Going straight into the Darwen team, he formed a right wing partnership with Tommy Marshall and soon there was a steady diet of goals, cup ties and an admiring public. He had an income from the football club and may also have done some odd jobs.

But a year later, after this initial excitement, he dropped out of the Darwen team for reasons which are not clear. This left him in a quandary. The football income would have dried up. He had no job. He could not go home because of the arrest warrant hanging over him. So he took perhaps the only option open to a fit young man: he joined the army.

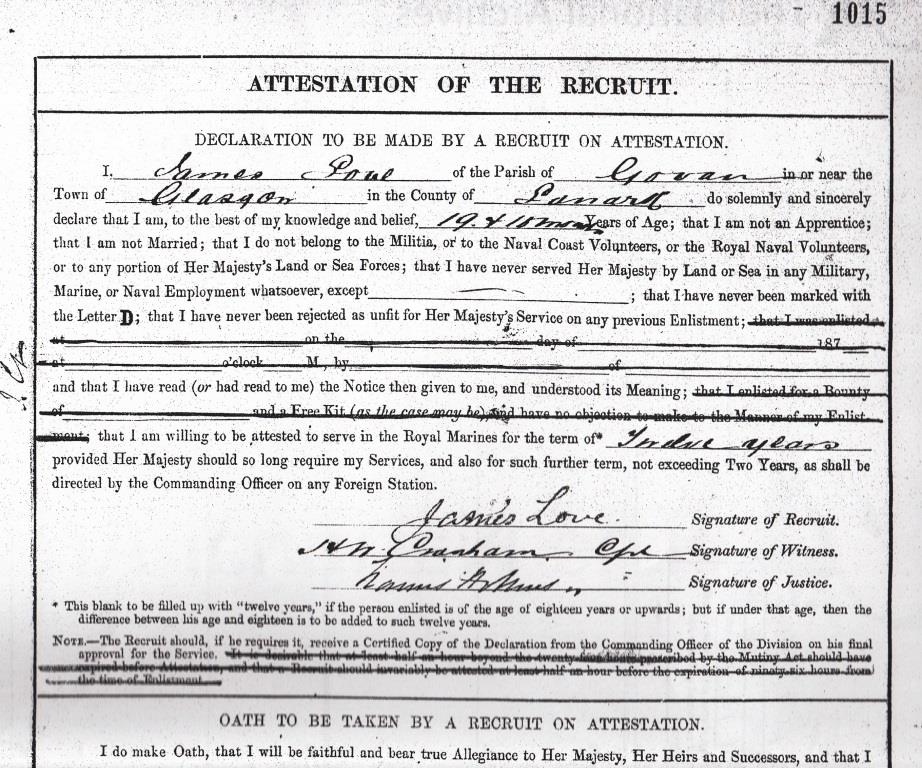

To be precise, he signed up with the Royal Marines in Liverpool on 24 February 1880 and I found his attestation papers at the National Archives.

By the 1881 census he is at Chatham Barracks, having been promoted to Corporal. Then in the summer of 1882 the Marines were called into action and embarked for Egypt, where the British were putting down a nationalist uprising by Ahmed Urabi. His forces had occupied Alexandria but after a defiant stand-off they were forced out by a two-day naval bombardment of the city. Love would have taken part in the subsequent occupation of Alexandria by the Royal Marines, and perhaps some of the fighting thereafter. But then he fell ill with a fever and, sadly, died in the military hospital in Ismailia. Corporal Love is commemorated on the memorial in Tel-el-Kebir cemetery.

But the story doesn't quite end there as there is one final, poignant, connection with Partick FC. After his death, Love's elder sister Jessie married one of the other Partick players, David Muirhead, and they named their son James Love Muirhead. He too met a sad end, killed in action in the first world war.

So that covers the story of Jimmy Love. What of Fergie Suter? His basic story is better known, and he even has an entry in the Dictionary of National Biography, albeit with errors. Suter was born in Glasgow in 1857, the third son of a stonemason recently arrived from Ireland. He grew up in Partick where he was an apprentice mason like his father, and appears in Partick teams from 1876 onwards. He was well established as a footballer when, out of the blue, he also had a strong financial imperative for leaving.

In October 1878, the City of Glasgow Bank collapsed suddenly and spectacularly, incurring huge losses for its 1200 shareholders who had unlimited liability. It sent financial shockwaves through Scottish society as the directors were jailed for fraud, and 80 per cent of the shareholders were bankrupted.

One of those shareholders was a prominent Partick builder called Peter McKissock, who immediately halted work on his projects and dismissed all his men including the stonemasons. Among them, it seems likely, was 21-year-old Fergus Suter. To make matters worse, in November the Partick masons went on strike in protest against reduced rates of pay.

So, with little prospect of finding work locally Suter must have cast envious eyes at Jimmy Love in Darwen and wrote to ask if he, too, could be found a position. Suter had already played there for Partick, so it was not exactly a leap into the unknown, and according to the Lancashire Evening Post article I have already quoted, Suter 'came in the guise of stonemason, but only worked in that trade for a week or two. After that he purely played football, and though this was years before professionalism was legalised, he never lacked money.'

I have to point out that there is an erroneous story, which has appeared in many books and articles, stating that Suter played for Turton before coming to Darwen. This story originates in Tony Mason's Association Football and English Society (1980), but from an examination of the original source material, a 1909 history of Turton FC, it is clear that Suter's appearance for Turton was at the end of the 1878/79 season, not the start, although it does confirm he was paid cash by Turton for an appearance in their Challenge Cup team. I have since found a report of the Turton Challenge Cup final, and it was played on 29 March 1879 - ie two weeks after the defeat to Old Etonians. Suter played as a guest for Turton, who lost 1-0 to Eagley, and so did Jimmy Love; it stands to reason that if one of them was paid, so was the other.

Suter had made his debut for Darwen on 30 November 1878 at Accrington, where a spectator recalled 'he simply electrified players and spectators alike with points in the game of which they had never previously dreamt'. A week later, he and Love played in their first FA Cup tie, against Eagley on 7 December.

If anything, Suter's immediate impact was greater than Love's as within two weeks of arriving he played a trial for Lancashire and went on to represent his adopted county on numerous occasions, while Love was never selected. Suter certainly found his vocation in football. In his second season, 1879/80, he was appointed club captain of Darwen, led the team to victory in the first Lancashire Cup final, and his brother Edward also joined from Partick.

But in the summer of 1880, without warning, he jumped ship and moved to local rivals Blackburn Rovers. Darwen protested furiously that Suter had been financially induced, but there was, of course, no proof - and precious little sympathy for Darwen in any case as they were suspected of paying Suter themselves. The chances are that Rovers made Suter an offer he could not refuse, either a straight cash payment or a large loan on easy terms to set up a pub.

However, I did discover another possible reason for Suter wanting to leave Darwen. According to a family legend, he fathered an illegitimate son by a servant girl, and the time of his move to Blackburn would have coincided pretty much exactly with the discovery that she was pregnant.

Whatever, it was a successful move and Suter was the first man to make a career as a professional footballer. He remained with Blackburn Rovers through a glorious decade in which they were the first northern side to appear in the FA Cup final, in 1882, and subsequently won the FA Cup three times in a row, in 1884, 1885 and 1886. Suter just found time to make one appearance in the Football League's inaugural season in 1888, and continued to live in the town as a publican until shortly before his death in 1916.

So there, in brief, is the background to the players who gave birth to professionalism in football. Love and Suter changed the game forever through a specific set of circumstances which provided the means, the motive and the opportunity to earn a living from the game.

Partick and Darwen were unlikely bedfellows, but between them they established the rationale for paying football players. It is quite a legacy.

Article copyright Andy Mitchell, not to be reproduced without permission.

Click here to read an article about this research in the Sunday Herald.

NB In the course of researching Love and Suter, I have accumulated a large amount of background material, references and family trees. If other researchers would like to consult this archive, please get in touch through the contact form on the home page.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed