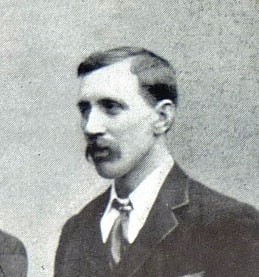

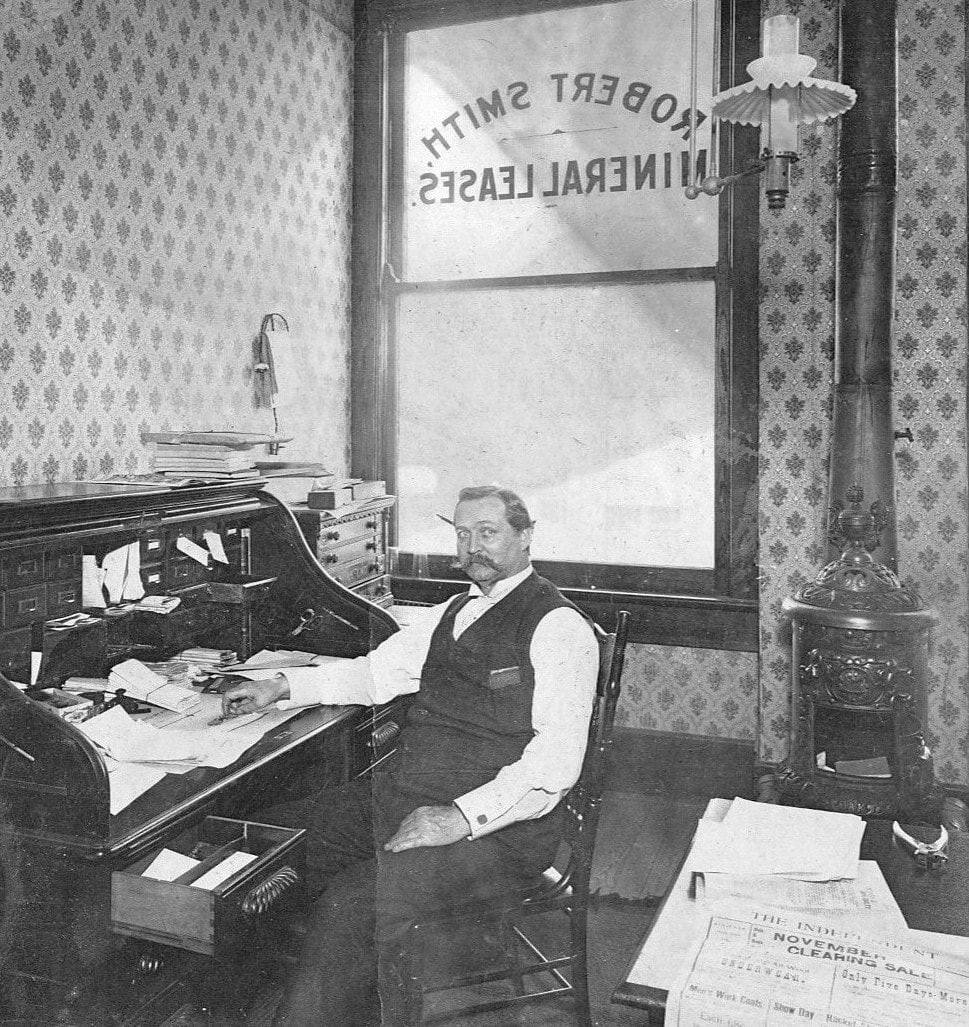

Yet there is an amazing mystery behind the man, as his true identity has been hidden for over a hundred years: Robert was his surname, not his first name, while Guérin was a suffix he adopted in adult life.

I would like to introduce you to Maurice Robert. That was the real name of FIFA's first President.

Little is known about the first two decades of his life but he must have learned English - a skill which was essential in years to come - as in 1898 Maurice Robert was accepted into the Society for the Propagation of Foreign Languages. By then he was working in commerce and living in Paris, in a narrow street in Montmartre that was to remain his home for the rest of his life.

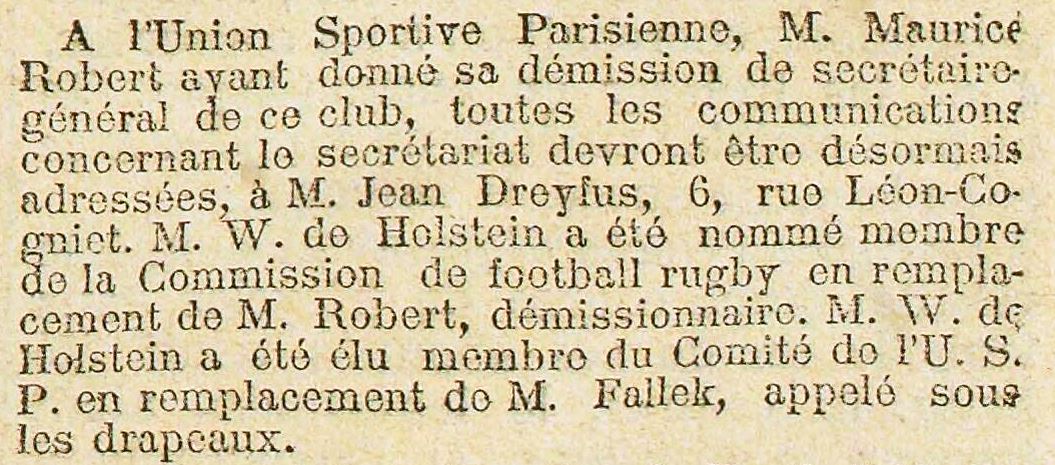

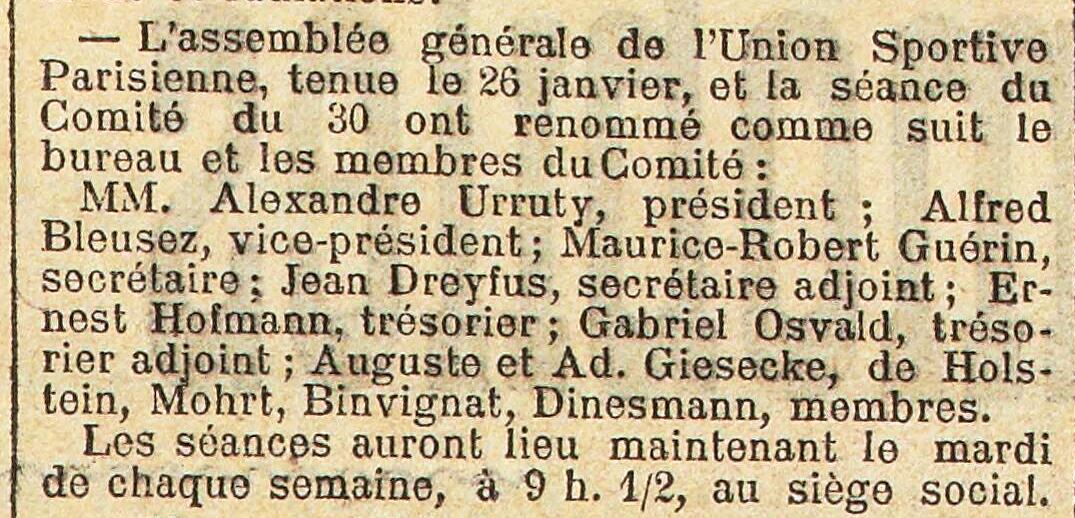

He joined Union Sportive Parisienne, a multi-sports club founded in 1896, but was not much of a player and became its secretary between 1900 and 1904. He was therefore mentioned regularly in the press as the club's contact for fixtures, which reveals that he was known as Maurice Robert until the end of 1900, then early in 1901 he changed his surname to Robert-Guérin.

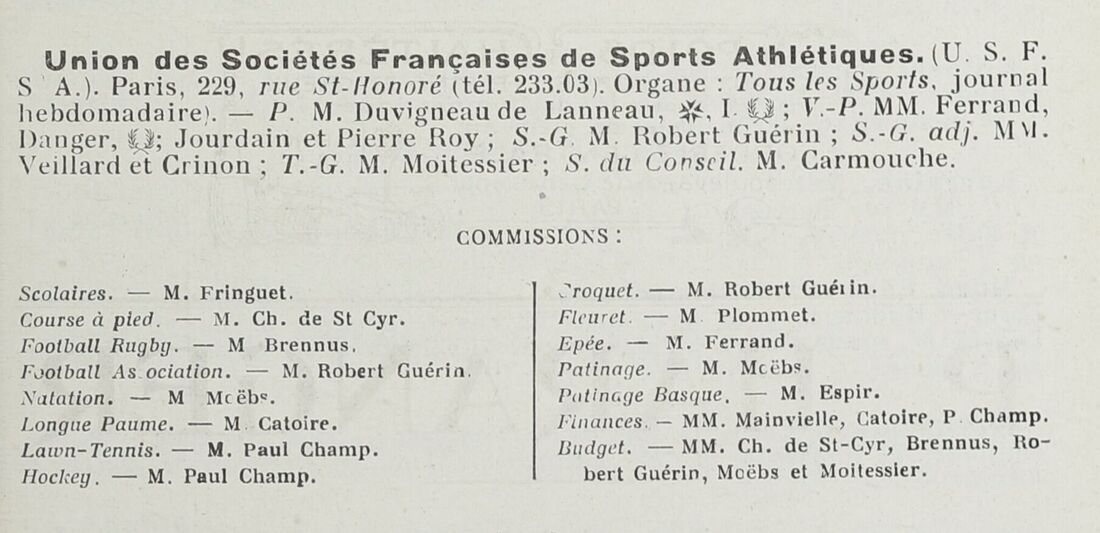

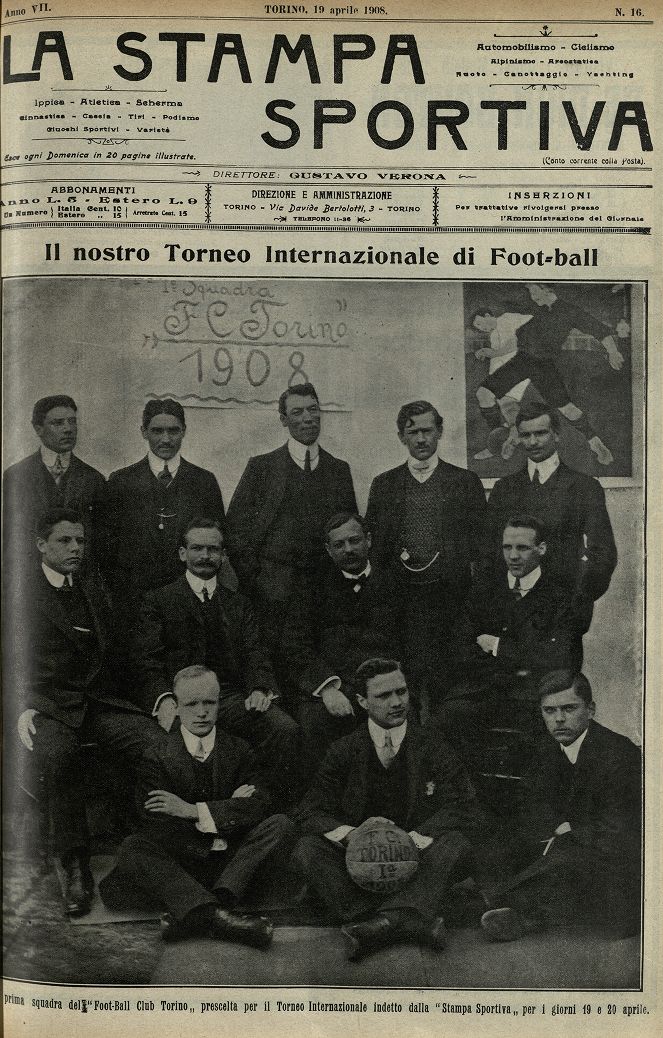

Maurice Robert-Guérin became more involved in sport and joined the USFSA, a national governing body for many sports, where he was in turn its treasurer and secretary, working from its base at 229 rue Saint Honoré in Paris. His first love at the time was football, refereeing several high profile matches, but he was also involved in a range of activities which no doubt helped him to make his way as a sports journalist.

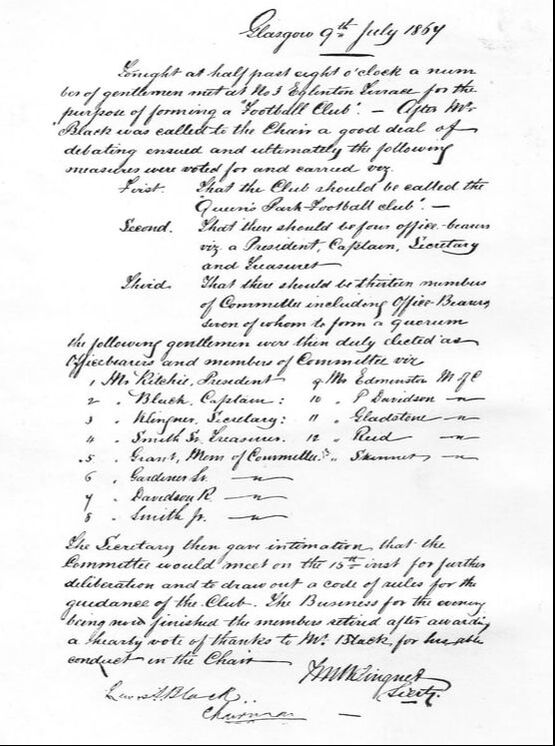

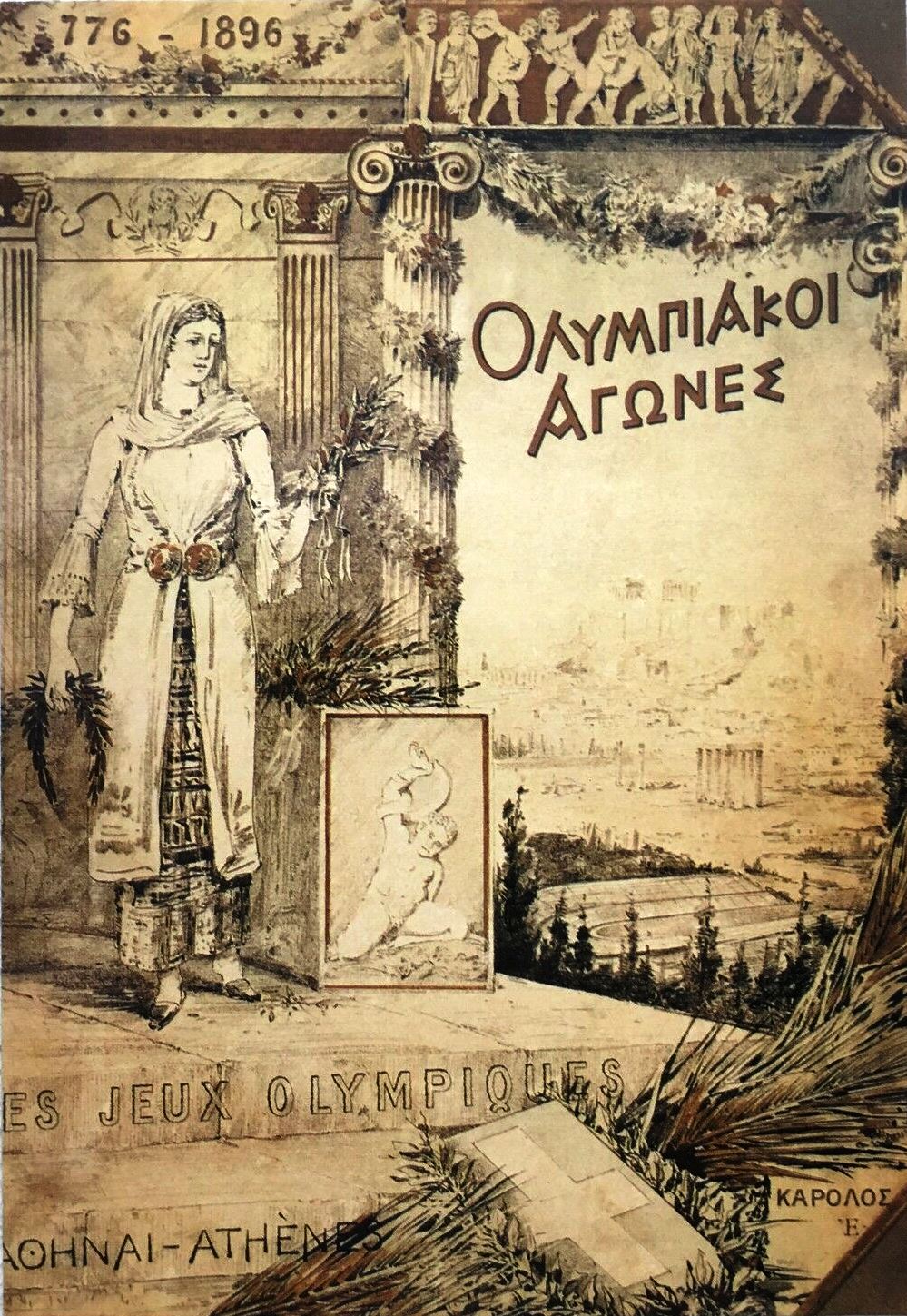

The story of the founding of FIFA is well known and Robert-Guérin recalled the spirit of the times for FIFA's 25th anniversary: 'It was not difficult to foresee in 1903 that football was going to become more popular all over the world. I decided to found the International Federation of Association Football, with the collaboration of very good friends.

'I was rather surprised that the initiative was not taken up by England, where football was triumphing. I though that, by rights, the chairmanship belonged to the Football Association of England.'

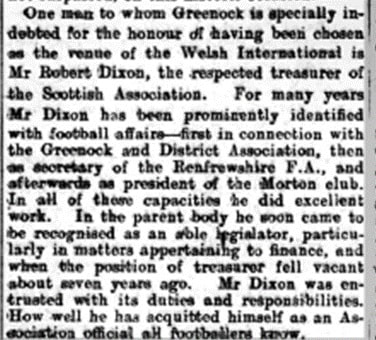

He went to London to meet Frederick Wall, the FA secretary, who listened but merely replied that he would refer the matter to the FA board. Robert-Guérin waited patiently for months but heard nothing, so he asked again and was invited back to London where, this time, he met Lord Kinnaird who was friendly but non-committal. 'It was like cutting water with a knife,' he recalled.

Faced with English prevarication, 28-year-old Robert-Guérin felt he had no option but go ahead without them, and called the meeting at which FIFA was established on 21 May 1904. Reluctantly he accepted the role of President, which was not a role he cherished but he remained at the helm of the fledgling organisation for two years until Englishman Daniel Woolfall was persuaded to take over in 1906.

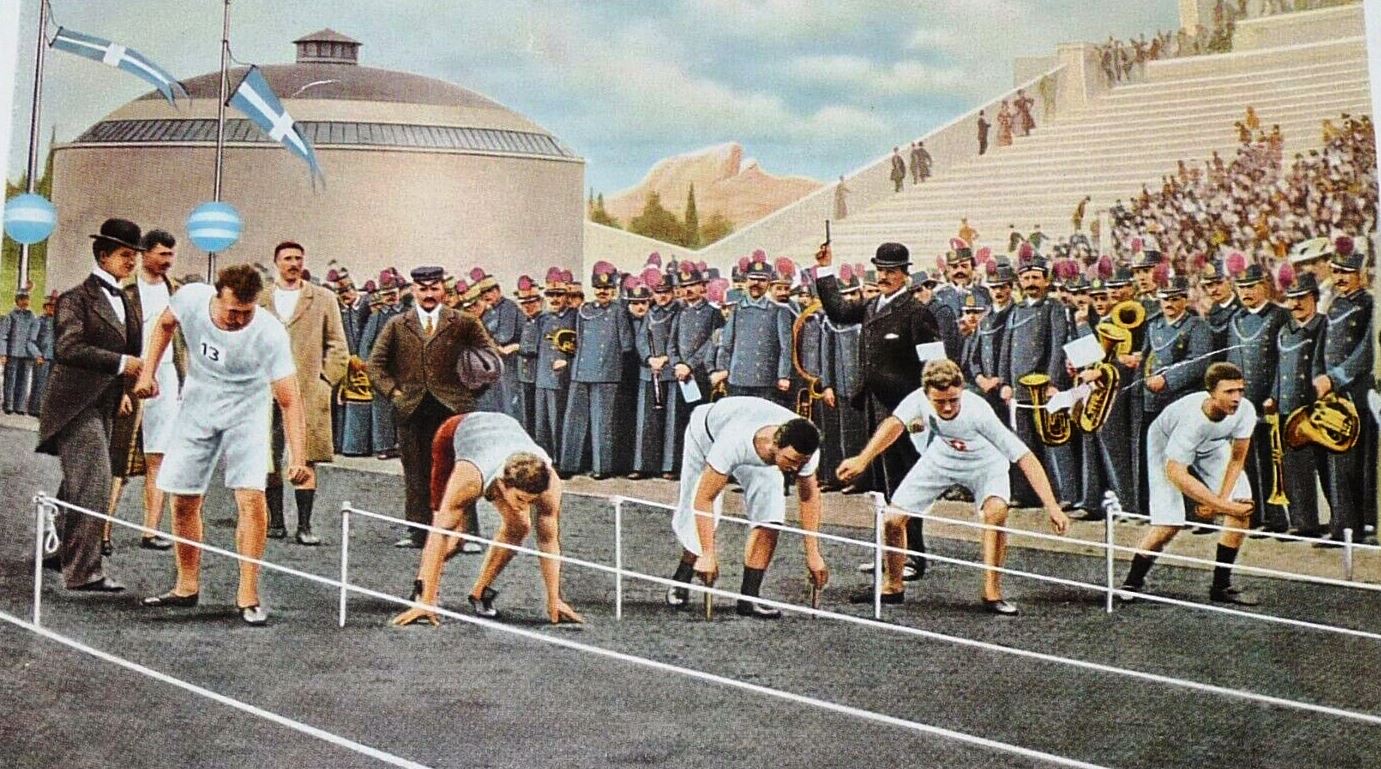

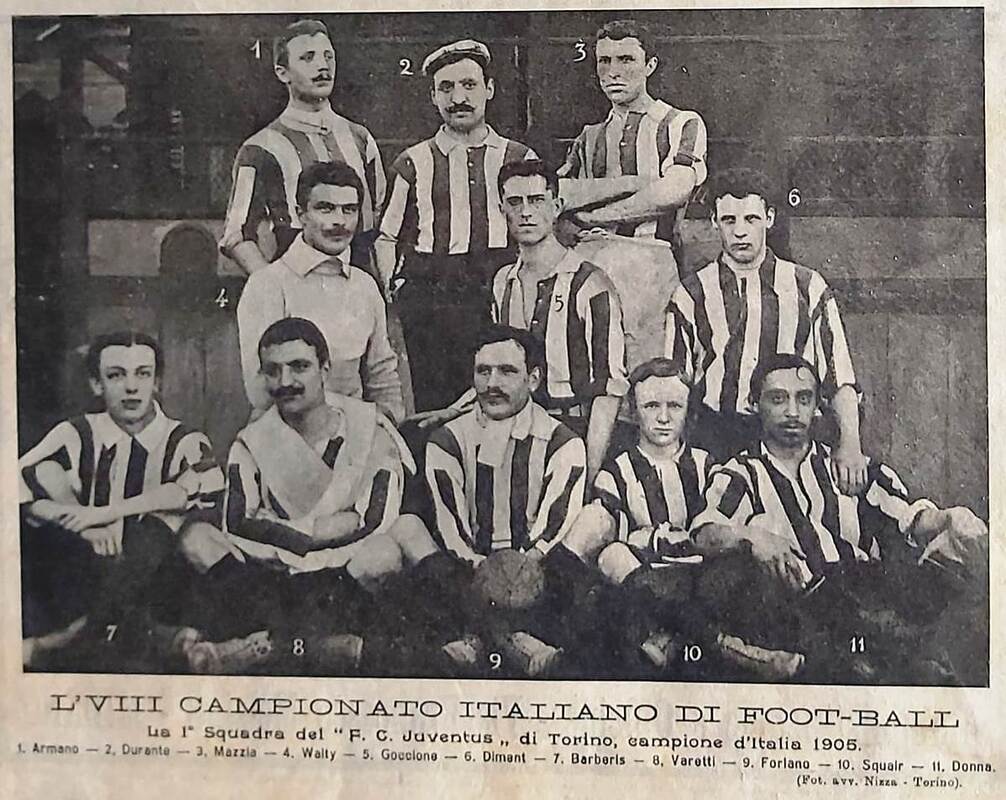

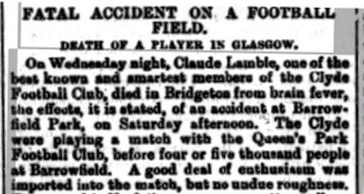

His time included defeats of 15-0 and 12-0 to England amateurs, and ultimately the humiliating 17-1 crushing by Denmark at the Olympics.

For the rest of his professional life, he was known as Robert Guérin, with the ambiguity of Robert being a first name or part of a double-barrelled surname. I cannot find any instance of him using Maurice as a journalist, and he appears always to have described himself simply as Robert-Guérin, sometimes with a hyphen, sometimes not.

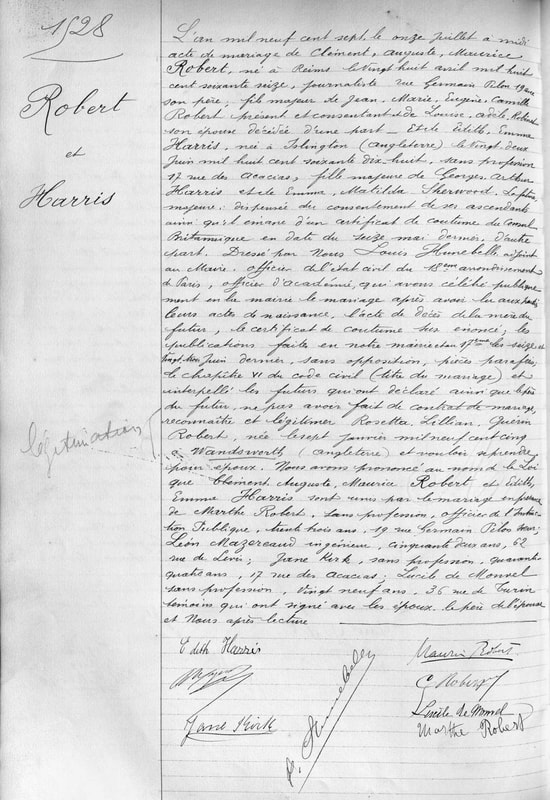

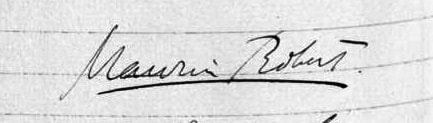

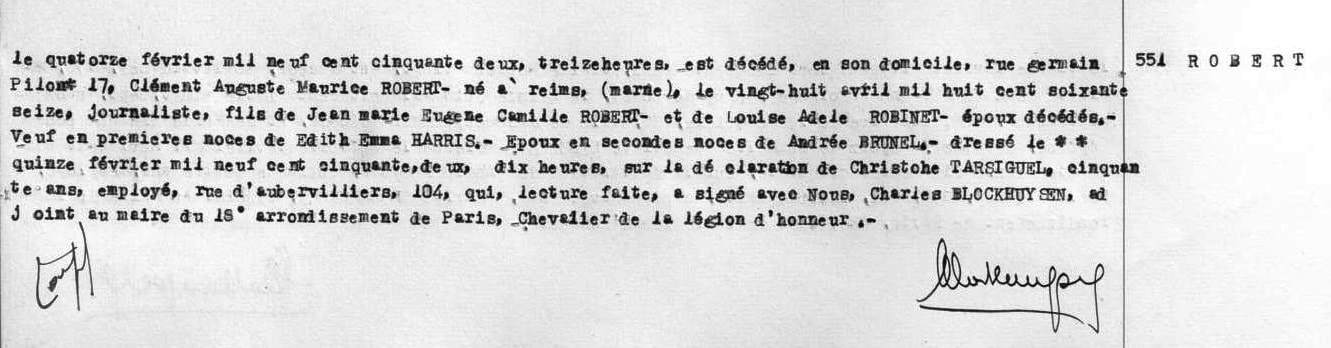

In his private life, however, his surname remained simply Robert. After Edith died in 1926 he remarried the following year to Andrée Brunel and again he signed the certificate as Maurice Robert.

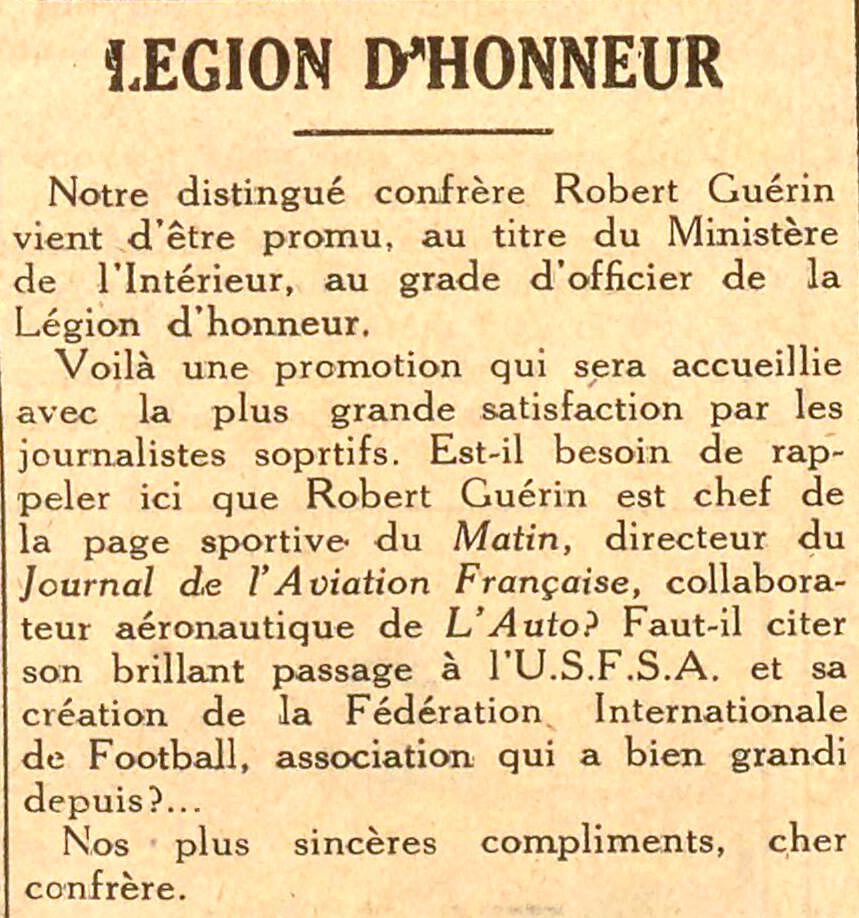

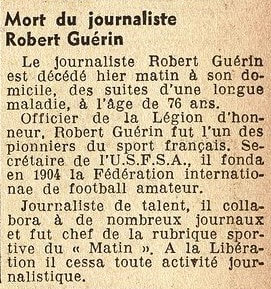

Having given up sports administration in 1908, he worked for most of his life as sports editor of Le Matin, and although he continued to report on football he developed a passion and expertise in aviation, writing for several specialist magazines. He was highly respected in his field, and was made a Chevalier of the Légion d'Honneur in 1922, then promoted to Officer in 1934.

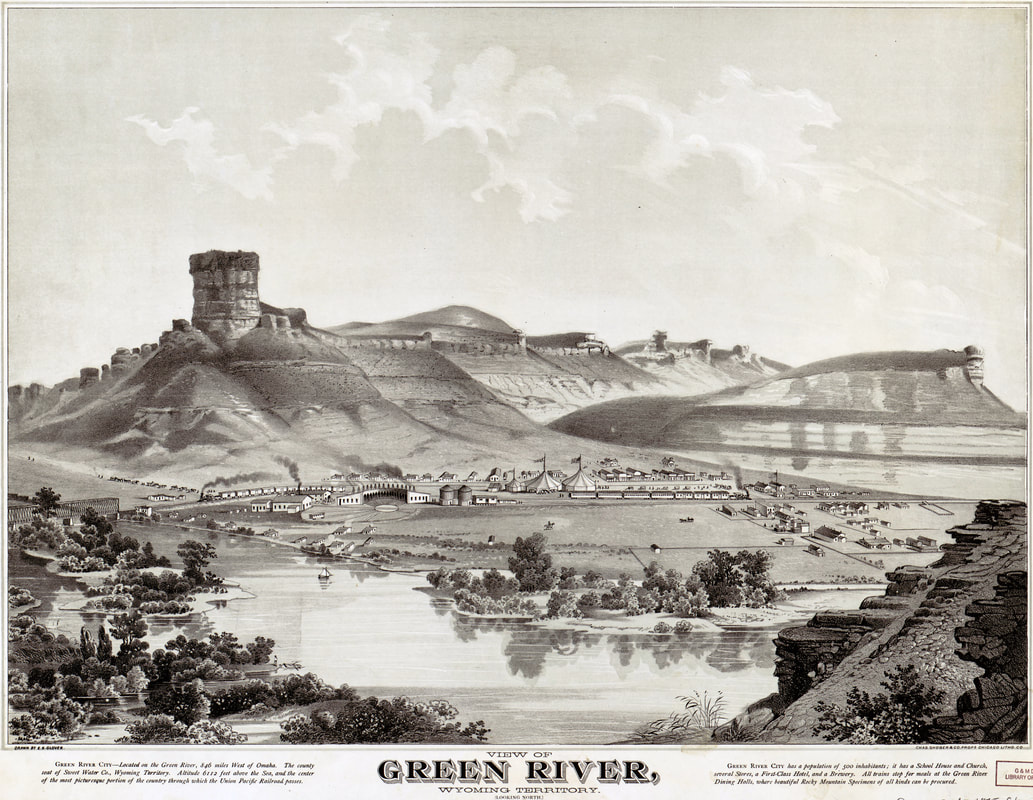

After Le Matin folded in 1944 (with its reputation sullied for taking a pro-German stance during the occupation) he was left impoverished, and that led to the only time he is known to have used another version of his name. A few years ago some of his personal letters came up at auction and they were apparently signed Clément Robert-Guérin. Written in the late 1940s, they revealed he was in difficult financial circumstances and losing his sight.

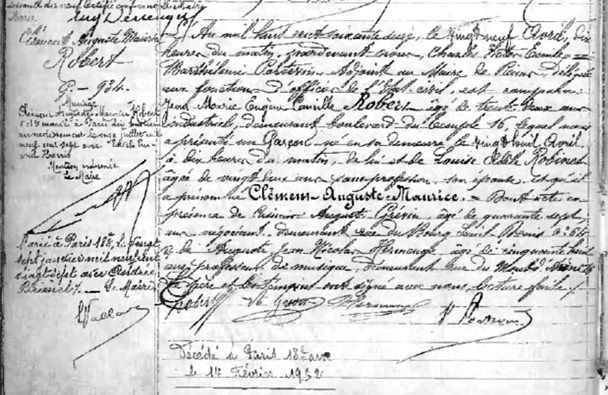

Clément Auguste Maurice Robert, also Robert-Guérin

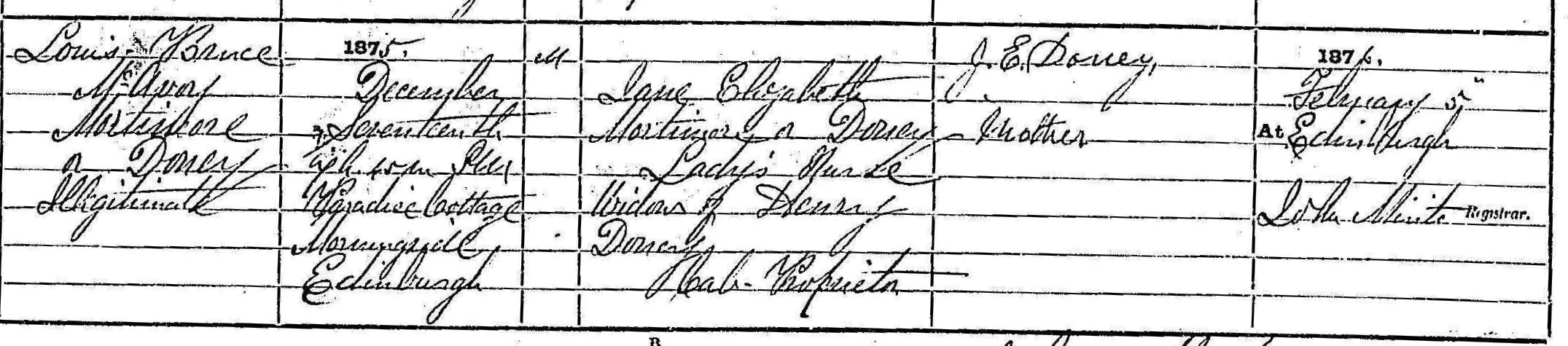

Born 28 April 1876 at 16 boulevard du Temple, Reims.

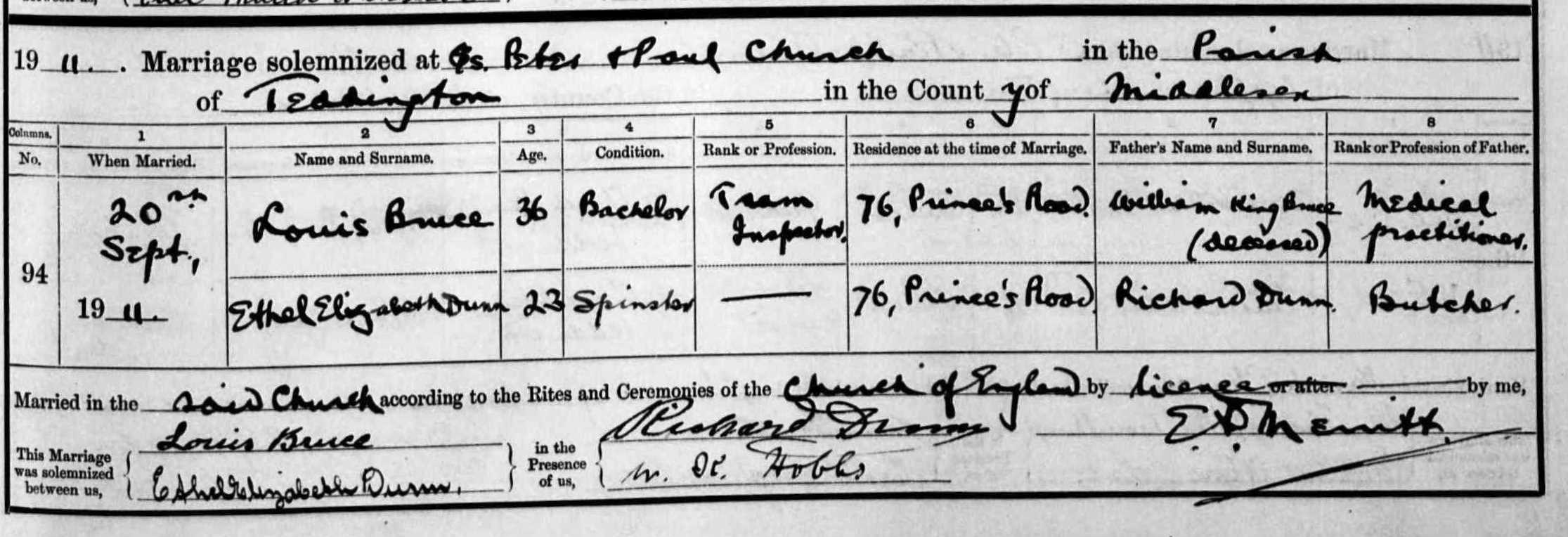

Married (1) 11 July 1907 to Edith Emma Harris.

Married (2) 27 January 1927 to Andrée Brunel

Died 14 February 1952 at 17 rue Germain Pilon, Montmartre, Paris.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed