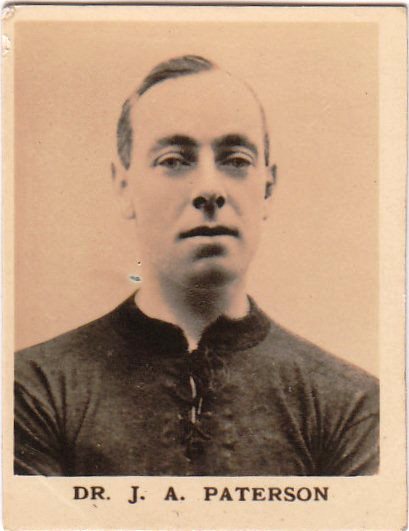

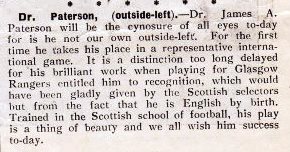

What it doesn't reveal is the extraordinary coincidence that led me to write it, one which I am sure will resonate with all sports historians. It just happened that my parents, who live in Edinburgh, mentioned that their next door neighbour's father had played football. So I duly went next door and spoke to Jimmy Paterson's daughter Mhairi, now in her eighties, who brought out a file of cuttings and photos.

I was also able to find newsreel footage of Paterson playing (and scoring) for Arsenal in 1926 on the British Pathe website [click on link]. She had never seen film of her father playing football before.

There was nothing for it but to write his story - especially when it became clear that no-one had done so before!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed