That was the challenge facing Clive Nicholson, who is Fred Spiksley’s great great nephew. He has devoted much of the last 20 years to researching Spiksley’s biography, and has dug deep into conventional and less likely sources to uncover every aspect of his life story. A huge amount of work left no stone unturned and the resulting book is substantial and fascinating, extending to 390 pages packed with detail and accompanied by numerous photos, several of which are new to me. Another factor that makes this book different is that instead of launching into the publishing world himself, Clive brought on board professional writers and designers.

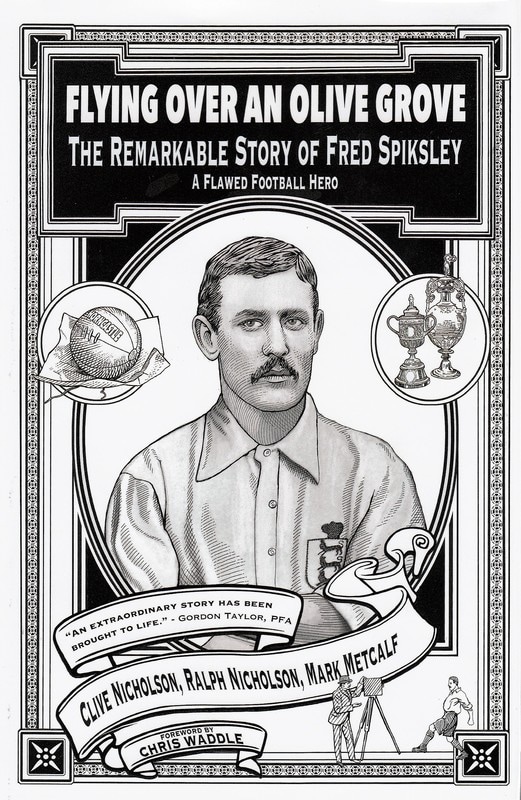

Fred Spiksley (1870-1948) was an England international left winger whose most famous period came at Sheffield Wednesday, but whose career encompassed a wide range of clubs.

Having written a biography of Arthur Kinnaird, I know from personal experience how difficult it can be to bring Victorian characters to life, and the authors do manage it very well for Spiksley, demonstrating an understandable fondness for his skills and forgiveness for his flaws. It turns out that Spiksley was not just a fine footballer of international class, who went on to an adventurous coaching career in several countries, he was also a compulsive gambler, a womaniser and possessed of a unpredictable temper.

There are anecdotes galore as the authors provide an insight into the precarious world of football in the early professional era: the brutal tackles, the appalling conditions for players and spectators, the financial pressures and the shady characters.

One of the reasons the book is interesting to a Scottish audience is the authors' claim that Fred Spiksley scored a hat trick for England against Scotland in 1893, which would have been the first. All the contemporary reports attributed the final goal to John Reynolds, but later on a number of observers, including Spiksley, claimed it for himself. The case for attributing the goal to Spiksley is not particularly well detailed in the book itself, but is outlined in great detail on their dedicated website, spiksley.com.

Having read it through carefully, some of the background research is impressive but I have to say I am not convinced, although the arguments have been accepted by others, including the influential englandfootballonline site. It was only many years later that people started to claim that Spiksley had scored a third. The main justification for the 'error' is that the journalists' view of the match was obscured, but I find it hard to believe that the reporters from Sheffield, who knew Spiksley well, did not recognise him as the scorer, or did not quickly correct such an obvious error for a local readership. Especially if, as the authors say, 'Fred was bombarded by a horde of Scottish reporters once he left the sanctuary of the pavilion'. Did they not ask him?

There is also the assertion that Spiksley was presented with a gold chain by the FA to mark his achievement. Again, there is no contemporary report of a presentation, nor an FA Council minute or note of expenditure in the accounts, and the chain is now lost.

Ultimately, it is impossible to prove either way, but there are many similar instances in football history of stories arising years after the event which have no foundation in the truth. In fact, the authors inadvertently perpetuate another of these, writing that Jack Lyall, Sheffield Wednesday’s goalkeeper, was 'picked to play for England only for it to be established that he had been born in Scotland' (page 262). Not true. There is no contemporary evidence to support this, and as far as I can gather this apocryphal story first emerged in Lyall's obituaries.

Another criticism is that the book would have benefitted greatly from a rigorous editor. I know the authors had a difficult time getting the book into print as their deal with a publisher collapsed, but there are numerous formatting errors and text repetitions (eg several times it was a 'miracle that no one was killed' in a crowded stadium). The text also sometimes veers off at a tangent, as their enthusiasm for detail gets in the way of a good tale. For example, the fact that an England player had a telephone in 1893 is interesting but a potted history of the development of the telephone industry is superfluous; and a bizarre paragraph about Britain's waning colonial ambitions in the middle of a review of the 1896/97 season (page 197) is utterly irrelevant.

Those quibbles apart, the book succeeds in bringing Fred Spiksley to life - notoriously difficult to achieve in football biographies - and deserves the wide audience it appears to be finding. It has benefitted from an innovative marketing campaign, using the whole toolbox of social media, personal appearances and interviews, publicity stunts and pestering journalists, which all conspired to boost sales, and it is now into a reprint; which teaches a lesson to other sports historians (like myself) who should really be better at publicity.

Flying Over an Olive Grove has a cover price of £19.99 hardback, and can be ordered post free from spiksley.com

RSS Feed

RSS Feed