James Morrison fought in an Australian uniform and is lauded as one of the ‘Black Anzacs’, yet he spent most of his life at Mains Farm in Doune, near Stirling, where he was born and died.

As a young man, James worked on his father Peter’s farm and was also a talented footballer with his local amateur side Vale of Teith. They were good enough to give St Johnstone a hard fight in the Perthshire Cup final of 1907, which went to three replays before Saints won, and again in 1908.

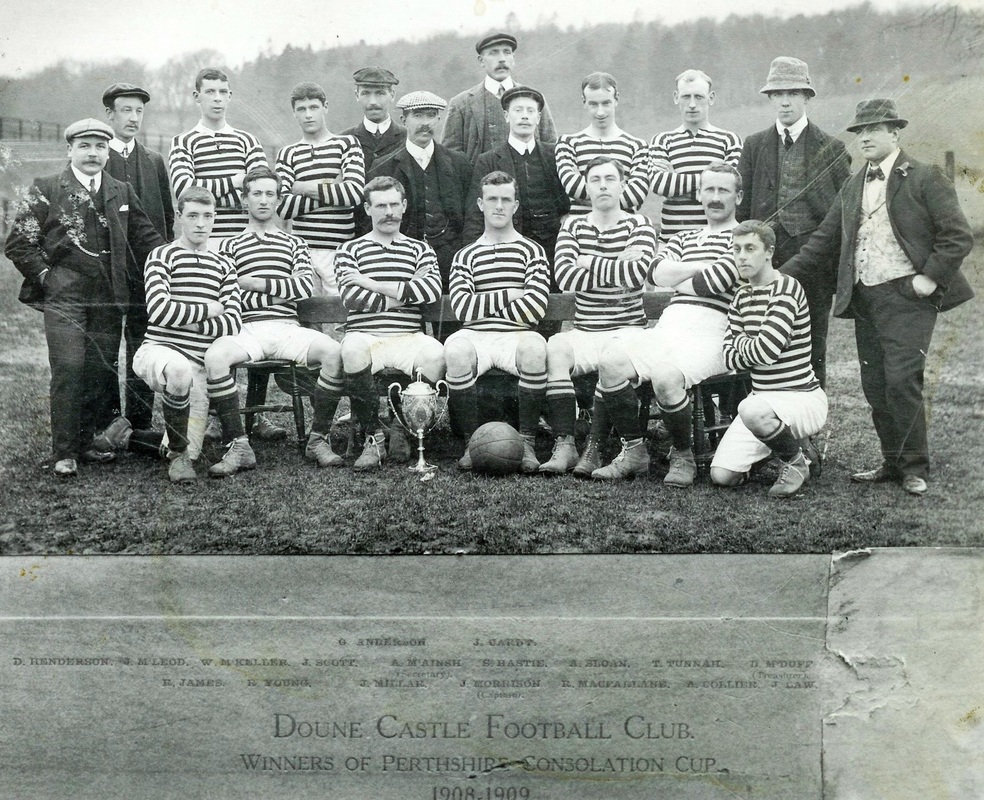

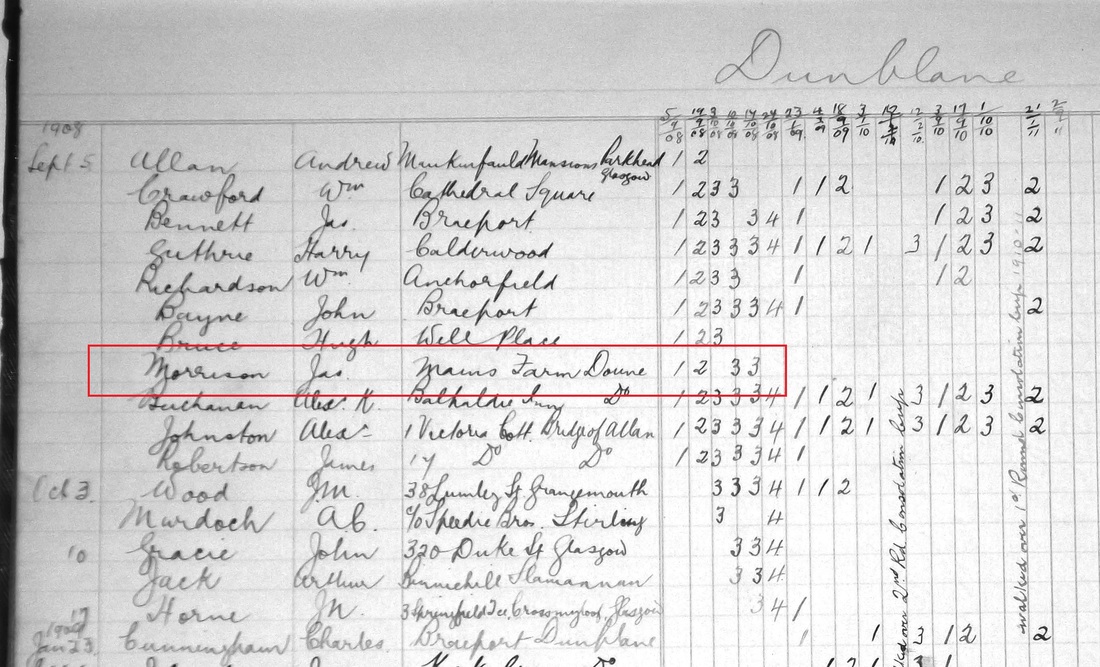

He played a few games for Dunblane, who were at that time a senior team, then returned to captain newly-formed Doune Castle to victory in the Perthshire Consolation Cup. The photo of the winning team from 1909 (above) has Morrison sitting proudly in the middle of the front row.

With limited employment opportunities at home, he emigrated in 1913 in search of adventure, heading to Perth, Western Australia, where his uncle lived, and found work building the new Trans-Australia railway.

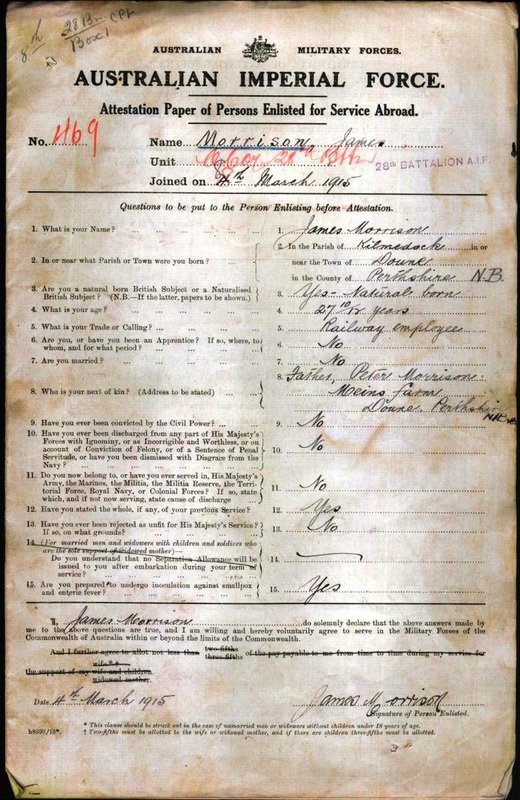

When war broke out the call went out throughout the Empire for men to fight and he enlisted in March 1915. Serving with the 28th Battalion of the AIF (Australian Imperial Force), he arrived at Gallipoli in September 1915 and was immediately pitched into action.

The death toll of the Anzacs (Australia and New Zealand Army Corps) at Gallipoli was appalling, but Morrison’s life was saved by illness after a few weeks of heavy conflict. His army medical record shows that he was admitted to hospital on 13 November suffering from enteritis and dysentery, and was shipped out to Malta to recover. It took three long months before he was deemed fit again for active service, and as the conflict in Turkey was coming to an end he spent a further month in Egypt before embarking for a different front line, this time in France.

Although two of the raiders were killed in a retaliatory barrage (including another Scot, Duncan MacLeod, born near Nairn), the raid was heralded as a success and gave a much needed boost to morale after the horrors of Gallipoli. The press seized the opportunity, dubbing the solders the ‘Black Anzacs’ as they had blackened their faces with burnt cork for camouflage. The authorities were equally keen to celebrate some good news, and as a reward, the soldiers who took part were invited to the AIF headquarters in Westminster, where they were served strawberries and cream.

While most of his battalion had to satisfy themselves with a short leave in London, Morrison took the opportunity to head north to Doune, where he was given a rapturous reception. He brought with him an Australian comrade, John McHugh (who would die of wounds the following year).

Morrison travelled home on leave again before the end of the conflict but spent most of his three years living on the front line. The places where he fought read like a catalogue of the First World War: Poizieres, Ypres, Ancre, Bapaume, Passchendale, Amiens, Somme and many others, yet when the conflict ended, astonishingly, he was virtually unscathed. Promoted to Corporal, he suffered his only wound at Morlancourt in the summer of 1918 but remained at his post.

Demobilised in 1919, James decided not to return to Australia and came back to Doune where he assisted his elder brother William on the family farm. When William died suddenly two years later, James took over the tenancy and settled back into peacetime life as a member of the kirk session at Bridge of Teith Church, and was president of the town’s bowling club.

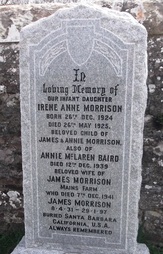

Doune’s quiet war hero died in 1941, having gone full circle, in the very farmhouse where he was born.

Born 1 May 1887

Died 7 December 1941

The story of the ‘Black Anzacs’ is told by Australian historian Doug Walsh on his website, http://blackanzacs.org.au/ and he has also recently written a book on the raid.

You can read about football in Doune on the Doune Castle AFC website.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed