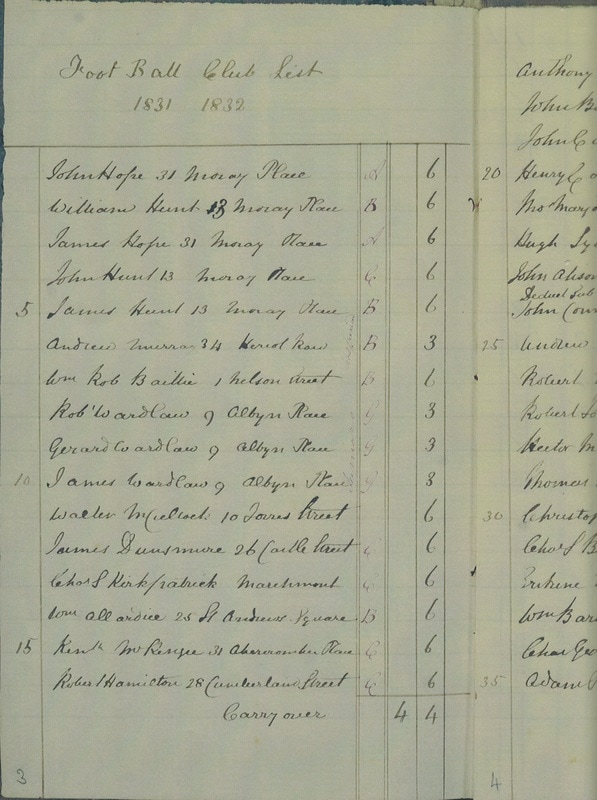

The Foot-Ball Club remained active from 1824 until 1841, with around 300 recorded members. As the world’s first known organisation dedicated to football it is a crucially important episode in the development of football, yet its full story has never been told.

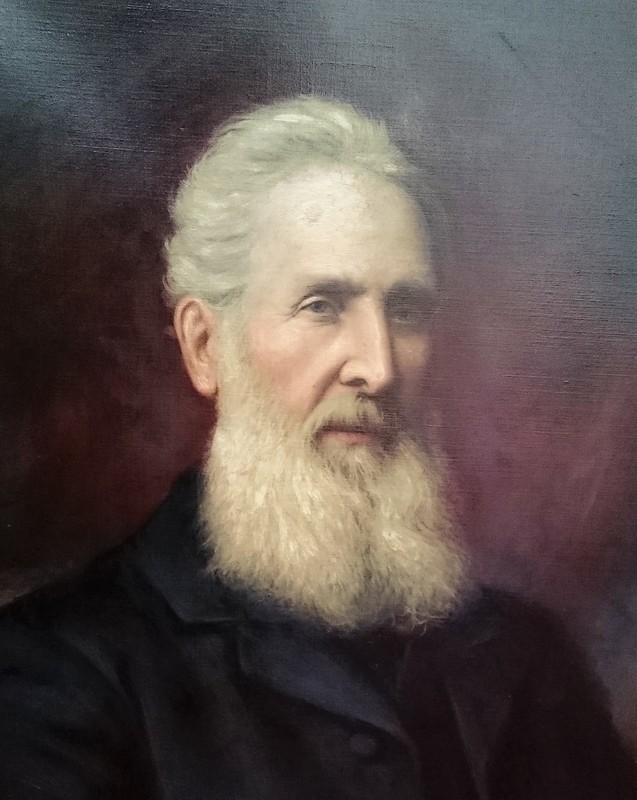

Now, I am working with John Hutchinson on a detailed history of the club, together with a biography of its founder, John Hope (pictured above). It is not just a story about football’s early days, it also looks at the players and their impact on Scottish society.

Hope is not given enough credit by historians for his contribution to the early development of football, where the focus is often on the founding of the Football Association in 1863, on the public schools, on Sheffield and so on. For example Sheffield FC, founded in 1857, have actually incorporated into their crest a claim to be ‘the world’s first football club’. It simply isn’t true. They might be the oldest surviving club, but the first? No way.

For a definition of what constitutes a sports club, this is what Hope himself had to say in a letter:

The football club resumed in October; the fun first-rate. I played for three hours on Saturday. Had business not kept me from the field this winter, I would have been in splendid wind. As it was. I am pretty swift, and am still a good hand at rolling down my opponents. Mr Esplin is very keen, and the life of the club. He brings out the men. He plays first rate. He gives a splendid ground kick - so sure. We mutually respect each other, but we are daily approaching to a keener contest. He has had more practice that I, and carries six years less than I do. He is short, and there is no upsetting him; but I hope to roll him next Saturday. The club gave occasion to some very spirited caricatures by my brother Jamie, I being, of course, the principal butt. We got new caps, very neat, improved by Esplin, like jockey caps.’

There, in one quote from the 1830s, are embodied all the essentials of a sporting club: the playing, the physical contact, the organisation, the team uniform, the rivalry, the respect for fellow members, the hope that it will all be better next week, the futile attempts to regain lost youth, the regret for not training enough and the laughter and camaraderie of a group of healthy and energetic young men united for one specific athletic purpose.

There are some startling links between the members of the Foot-Ball Club and the next generation of footballers. Here are two prominent examples:

James Kirkpatrick, an FA Cup winner with Wanderers in 1877 and captain of Scotland in the first unofficial football international of 1870, was son of Charles Sharpe Kirkpatrick, a member of the Foot-Ball Club in 1831.

Francis Moncreiff, captain of Scotland in the first international rugby match against England in 1871, was son of James Moncreiff, who was a member of the Foot-Ball Club in 1832.

There are a number of other football connections, from father to son.

The members also included future Members of Parliament, a Lord Advocate and two Presidents of the Royal College of Surgeons.

Thanks to this analysis, we can now demonstrate that this was not just a quirky, historically-isolated football club for gentlemen in one particular city, but one which spawned a close-knit web of interests and relationships which had a significant influence on the early and long term development of the game of football, and on Scottish society in general.

So, who was John Hope? Born in 1807, he was a lawyer, he was extremely wealthy, never married, and devoted his fortune and his energy to causes he believed in.

Some of his beliefs will be judged today’s moral standards as unpleasant, bigoted and misguided. His views on religion and alcohol, for example, would make you wince, but reflected the views of many others in the 19th century.

Hope was principally a social reformer who spoke up for the poor and the downtrodden, for example leading a campaign to introduce the Saturday half-holiday in Edinburgh, and providing country excursions for thousands of slum kids. In particular, he believed in the benefits of sport and exercise, and could loosely be described as an advocate of muscular Christianity. That included football.

A highlight of his football club papers are the rules he wrote in 1833 which, although simple, indicate a kicking game between sides, with a defined playing surface and goals. They predate the Cambridge Rules of 1848 which are generally seen as the earliest attempt at codification, but contain many of the same principles.

The club correspondence is extensive. A letter in 1825 from a member who had gone to London describes how much he missed the action. Another from a member who had gone to Cambridge University, effectively said that he didn’t see much prospect of football catching on there. And one from 1841 is the final item in the club’s history, a letter from a John Campbell asking if he could join. He seems to have been too late, as there is no recorded response. Around that time the Foot-Ball Club was wound up.

After that, it is clear that young men did continue to play football in Edinburgh, but exactly how, and where, is hard to determine.

The link to John Hope? The silversmith who designed the medal, James Mackay, had a son James who was schoolmate of John Hope and a member of the Foot-Ball Club – so he was no doubt able to advise on the correct manner of play for the image.

John Hope wasn’t done yet. In 1854 he opened a playground in Stockbridge, where he encouraged boys as well as girls to play football. He laid down the rules of play – which bear similarities not just to his 1833 rules, but also to the future codes for association football. There was no hacking, no handling, and goals were scored between the posts.

Then, when association football finally came to Edinburgh in the 1870s, John Hope founded one of the city’s first clubs for the soldiers in his volunteer regiment, the 3rd ERV. He actually kicked off their first match, and was presented with the trophy when they won their first cup.

When Hope died in 1893, he left most of his fortune to the Hope Trust, which preserved his papers, over 200 boxes of them, in our national archives, now called the National Records of Scotland. The football records were discovered by the historian Dr Neil Tranter, of Stirling University, who first wrote about the club in the 1990s, and we are now researching it in greater detail, a far reaching project which will culminate in a full scale book later this year.

Meanwhile, we have recently published an article in the academic journal Soccer & Society. It is a subscriber publication which can be accessed at this link, but for those who do not have a subscription please get in touch via the contact form on the home page.

A report on our findings has also been published in Scotland on Sunday, and can be read via this link.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed