In 1891, the first football club in France had a problem: customs officials were suspicious that their newly imported corner flags carried the emblem of some political party.

An Englishman called William Sleator went to see the Prefet de Police to sort it out, and had to start by describing this new-fangled game of football. The policeman was mystified, asking why they couldn’t just play the game indoors. But Sleator not only charmed the official into releasing the flags, he even talked him out of charging customs duty on the goalposts which had been brought over from England.

Sleator came to be considered the ‘father of French football’ and for many years football veterans would raise a glass and toast his memory. He was even presented with the French Football Federation’s gold medal for services to the game, but his legacy and the adventures of his fellow pioneers are now largely forgotten.

Although British sailors had introduced football to France at ports like Le Havre in the 1870s, and there was a failed attempt to set up a Paris club in 1889, the genesis of the modern game can be pinpointed to 30 October 1891.

On that day, at the Café Francais on rue Pasquier, a football club was founded by a group of young English and Scottish sportsmen. They voted narrowly to play association rather than rugby rules, agreed to call the club White Rovers and elected Sleator as treasurer.

Having successfully sourced essential playing gear like those flags and goalposts, the team’s first match, against a YMCA eleven, was very low key, as Sleator later related: ‘We had ten spectators, most of them boys. One of the boys told his father he had seen English lads, in uniforms, kicking a huge ball about, knocking it with their heads, and charging each other to get at it. The boy’s father said the English were mad enough for anything.’

White Rovers worked hard to establish the game in France and were one of six clubs in France's first-ever football championship in 1894. Sadly they were never crowned champions and after losing the inaugural final to Standard AC in a replay, they also finished runners-up for the next three seasons. The championship, somewhat incongruously, was backed by the New York Herald, whose European edition was based in Paris, and whose proprietor James Gordon Bennett donated a magnificent silver trophy.

Playing in white shirts with a large blue Maltese cross, White Rovers were based in the Paris suburb of Courbevoie, near the railway station at Bécon-les-Bruyères, where they were granted the use of a ground by the Compagnie des Chemins de Fer de l’Est.

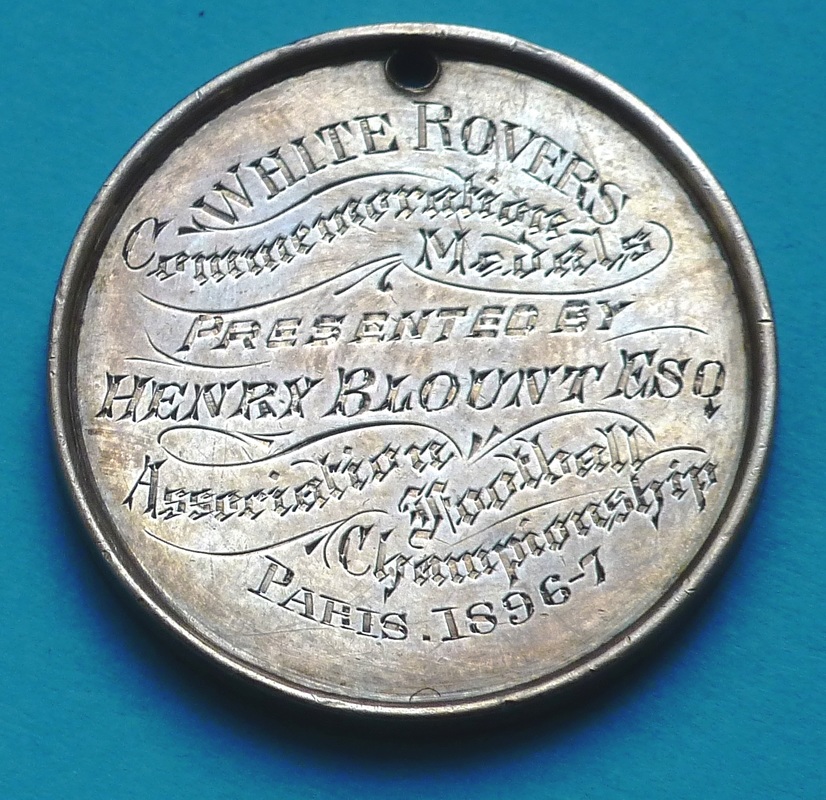

This was thanks to a director of the railway company called Henry Blount, son of the British Consul and a well-known socialite, who became the club’s patron. In 1897, Blount felt so proud of the players as once again they fell at the final hurdle that he presented them with silver medals to commemorate their efforts.

White Rovers lasted just eight years, but in that time they were hugely influential, inspiring French players to form their own clubs, the first being Club Français in 1892, which was founded by Charles Bernat and Eugene Fraysse who had learned the game while at school in the UK.

Not long after that, as some of the original players drifted back to the UK, the club foundered and it did not survive to the end of the century. However, its legacy remains.

Today, although few French fans know the debt they owe to the pioneer players, the vibrant football culture in France can trace its roots right back to the heady days of William Sleator and his White Rovers.

Who were the White Rovers pioneers?

William Henry Sleator was born in Worcester in 1871 and grew up in the town’s Lansdowne Inn, run by his parents, but his father died before his second birthday. Although his mother remarried to the man who took over as landlord, that man also died ten years later, leaving her in sole charge of the tenancy.

Despite these upheavals, William and his elder brother Alec were well educated at Worcester Middle School and Barbourne College, where they enjoyed sport and as well as playing football, both were active members of Worcester Rowing Club.

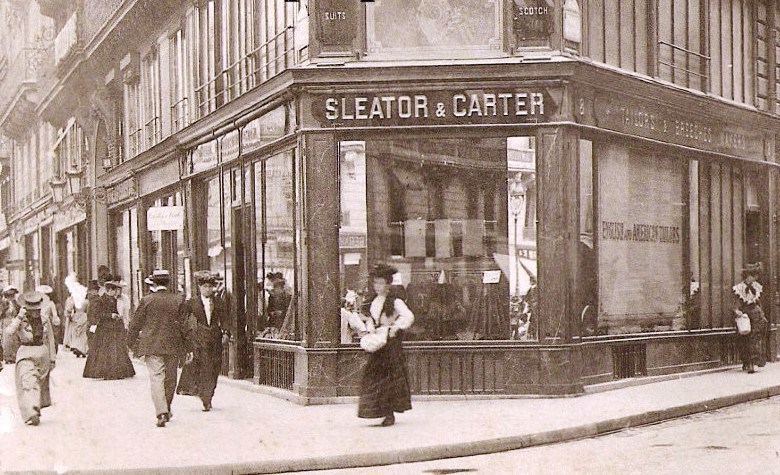

Alongside Sleator at the club’s foundation in 1891 was Walter Herbert Hewson (1868-1945), appointed secretary. He was born in Surrey and set up in business in Paris as a clothing outfitter.

One of the most prominent players was Jack Wood (John Bertram Wood, 1872-1921) from north London, who went on to play for Standard AC and Club Français, then became a referee and officiated at the 1900 Olympic football tournament; his brother Tom also played for White Rovers.

Edward Barclay (1872-1932) was a Scottish lawyer who attended Westminster School before taking a law degree at the University of Paris. He spent the rest of his life in Paris, where he was President of the British Chamber of Commerce.

Robert James MacQueen (1871-1921) was a tailor like Sleator, but left Paris for Chile with his French wife, returning to England shortly before his death.

Claude Farnworth Rivaz (1872-1958), a British artist who was educated at Westminster and spent three years studying in Belgium, where he played for Royal Antwerp, before coming to Paris around 1894 and joining White Rovers.

These are just some of the early White Rovers players, but many others are recorded only by their surname in reports and are difficult to identify. I would welcome any further information and in particular a photo of William Sleator.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed