This was the first time poison gas was used on the Western Front, and not surprisingly the defending soldiers abandoned their trenches and fled. Once the initial panic subsided, the five mile break in the Allied defensive line was filled by Canadian troops who had been in the next segment.

In a desperate action over the next two days, the Canadians held firm to prevent a German breakthrough, but at terrible cost: over ten per cent of them, around 2,000 men, were killed. Many of the bodies were never recovered.

One of them was Sergeant William Prince of the 10th Battalion Canadian Infantry (Alberta Regiment). However, once the dust had settled came the strange discovery that it was not his real name. He was actually William Eadie, a Scot from Dunblane who had been a goalkeeper with Queen’s Park, Partick Thistle, East Fife as well as his home town team.

So, how did a Scottish footballer come to be fighting with the Canadian infantry under an assumed name?

William was born on 14 June 1882 at Calderwood Cottage in Dunblane, to David Eadie, a cotton dyer at the local mill, and his wife Mary. He was the youngest of four sons who would all go on to be decent players: James would captain Perthshire while with Dunblane and go on to be a regular for Queen’s Park, while David and Alexander played for a local amateur team, Strathallan.

William also started with Strathallan but when his work took him to Glasgow he joined his brother at Queen’s Park. He only made around a dozen first team appearances, sometimes alongside his brother, and in 1906 he signed for St Mirren but only made the first team once. However, as a reserve and an amateur he was free to play regularly for Dunblane and for three seasons was the regular custodian, helping the team to win the Perthshire Cup in 1906, reach the Scottish Qualifying Cup semi-final twice, and was capped by the county.

When Partick Thistle required an emergency replacement for their injured goalkeeper, they turned to William in December 1908 and he played five times. What happened to him for the next four years is not clear but in January 1913 the ‘well known amateur’ was reported to have signed for East Fife. Then on 20 March that year he sailed from Glasgow for a new life in Canada (despite being named in the East Fife team for that day!)

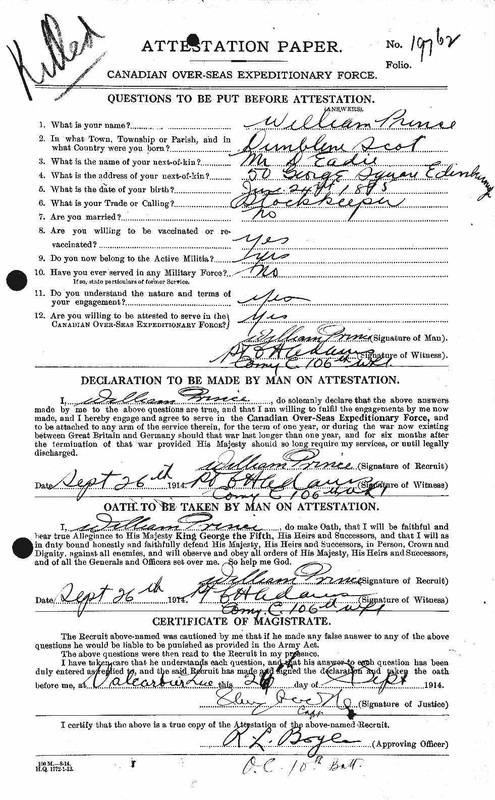

When war broke out, like so many others, he wanted to join the fight and at Valcartier in Quebec, on 26 September 1914, he signed up for the Canadian Expeditionary Force.

Yet there is something very strange about his attestation paper: he signed his name three times as William Prince, and cut 13 years off his age with a date of birth of 24 June 1895; however, he named his next of kin as his brother, David Eadie, at an address in Edinburgh. Compounding the mystery, his medical form gives his height at 5 feet 3 inches, surely too small for a goalkeeper.

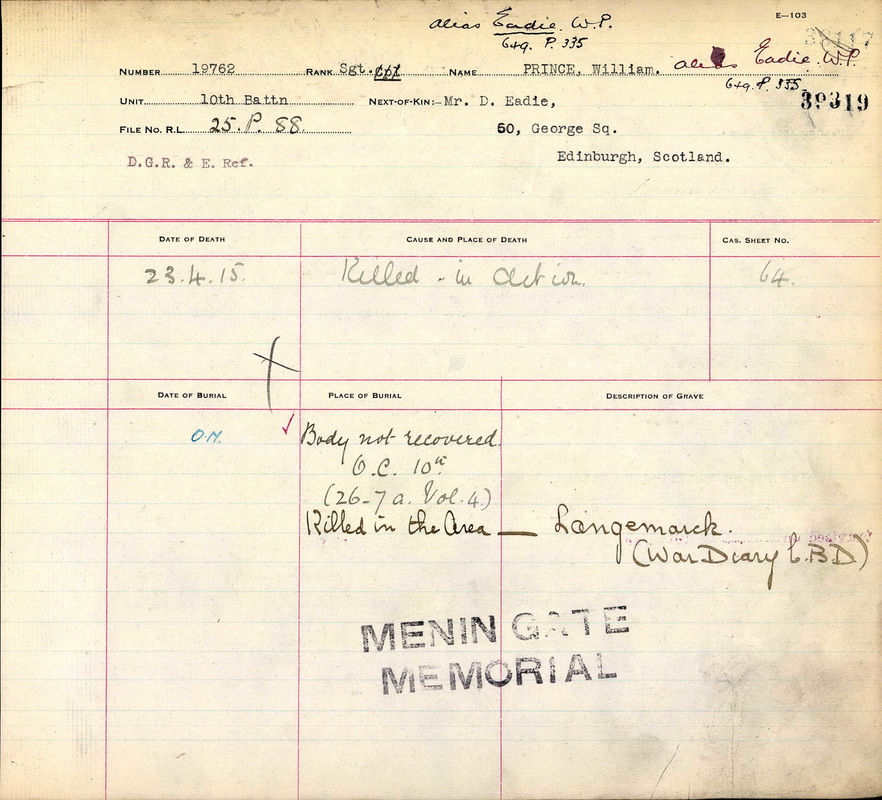

Was it a gross clerical error, mixing up two men? Was he trying to hide something? We may never know, but the name certainly stuck as seven months later, on 23 April 1915, Sgt William Prince went into a hail of bullets on the Western Front. His military record states ‘Killed in action’, ‘Body not recovered’ and ‘This soldier enlisted under an assumed name’. As far as the Canadian Army was concerned the matter was closed.

His sacrifice is commemorated on the memorial known as The Brooding Soldier just north of St Julien in Flanders. The inscription reads: ‘This column marks the battlefield where 18,000 Canadians on the British left withstood the first German gas attacks, 22 to 24 April 1915. 2,000 fell and here lie buried.’

He is recorded on the Menin Gate Memorial to the Missing as ‘Eadie W.P. served as Prince W.’ but despite coming from a well-known local family is not named on the Dunblane war memorial; this was because families had to ask for the honour and by then his father had died and his mother and brother had moved to Edinburgh.

There are no known photos of William Eadie, and the mystery of his military name change will probably never be satisfactorily resolved. He is one of at least 18 footballers from Dunblane who lost their lives in the First World War, and whose stories will be told in my forthcoming book about the club.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed